Common Conversational Words and Phrases in Italian

By mastering the basics of conversation in Italian, you put yourself and the person you’re talking to at ease. Everyone should learn essential Italian conversational words and phrases before traveling to Italy. These words and expressions are sure to come up in most everyday conversations.

Courteous phrases

Being polite is just as important in Italy as anywhere else in this world. The following words and phrases cover most of the pleasantries required for polite conversation. After all, learning to say the expressions of common courtesy in Italian before traveling is just good manners.

sì (yes)

no (no)

per favore; per piacere; per cortesia (please)

Grazie (Thank you)

Molte grazie (Thank you very much.)

Prego! (You’re welcome!)

Si figuri! (It’s nothing.)

Mi scusi. (Excuse me.)

prego (by all means)

Può ripetere, per cortesia? (Can you please repeat.)

Personal pronouns

Once you’ve mastered the common pleasantries, the next important thing to learn is how to refer to people. The most common way is by using personal pronouns. In Italian, the pronouns (you and they) are complicated by gender and formality. You’ll use slightly different variations of these words depending to whom you are referring and how well you know them.

Io (I)

lui (he)

lei (she)

noi (we)

tu (you [singular])

lei (you [singular/formal])

voi (you (plural/informal])

loro (you (plural/formal])

loro (they)

Use the informal

tu (singular you) and

voi (plural you) for friends, relatives, younger people, and people you know well. Use the formal

lei (singular you) when speaking to people you don’t know well; in situations such as in stores, restaurants, hotels, or pharmacies); and with professors, older people, and your friends’ parents.

The formal loro (plural you) is rarely used and is gradually being replaced by the informal voi when addressing a group of people.

References to people

When meeting people in Italy, be sure to use the appropriate formal title. Italians tend to use titles whenever possible. Use the

Lei form when using any of the following titles. A man would be called

Signore, which is the same as Mr. or Sir. An older or married woman is called

Signora and a young lady is called

Signorina.

It is also helpful to know the correct vocabulary term for referring to people based on their age, gender, or relationship to you.

uomo (a man)

donna (a woman)

ragazzo (a boy)

ragazza (a girl)

bambino [M]; bambina [F] (a child)

padre (a father)

madre (a mother)

figlio [M]; figlia [F] (child)

fratello (a brother)

sorella (a sister)

marito (a husband)

moglie (a wife)

amico [M]; amica [F] (a friend)

In Italian, there are four words to cover the English indefinite articlesa and an. For masculine words, you would use uno if the word begins with a z or an s and a consonant and you would use un for the rest. For feminine words, you should use ‘un for words beginning with a vowel and una for words beginning with a consonant.

Phrases for travelers

There are some Italian phrases that are particularly helpful to international travelers. Below are several phrases may come in handy during your stay in Italy.

-

Mi scusi. (Excuse me. [Formal])

-

Non parlo bene l’italiano. (I don’t speak Italian well.)

-

Parla inglese? (Do you speak English? [Formal])

-

Parlo inglese. (I speak English.)

-

Mi sono perso. [M]; Mi sono persa. [F] (I’m lost.)

-

Sto cercando il mio albergo. (I’m looking for my hotel.)

-

Sì, lo so. (Yes, I know.)

-

Non lo so. (I don’t know.)

-

Non so dove sia. (I don’t know where it is.)

-

Non capisco. (I don’t understand.)

-

Capisco, grazie. (I understand, thanks.)

-

Può ripetere, per cortesia? (Can you repeat, please? [Formal])

-

È bello. (It’s beautiful.)

-

È bellissimo. (It’s very beautiful.)

-

Vado a casa. (I’m going home.)

-

Domani visitiamo Venezia. (We’ll visit Venice tomorrow.)

-

Due cappuccini, per favore. (Two cappuccinos, please.)

-

Non lo so. (I don’t know.)

-

Non posso. (I can’t.)

-

Non potevo. (I couldn’t.)

-

Non lo faccio. (I won’t do it.)

-

Non dimenticare! (Don’t forget!)

-

Lei non mangia la carne. (She doesn’t eat meat.)

-

Non siamo americani. (We aren’t American.)

-

Il caffè non è buono. (The coffee isn’t good.)

-

Non è caro! (It’s not expensive!)

It’s possible to use more than one negative in a sentence. For example, you may say Non capisce niente (He/she doesn’t understand anything). Generally, you may just put non in front of your verb to negate your sentence, such as m‘ama non m‘ama(he/she loves me, he/she loves me not).

Common places and locations

It is also helpful to know the correct vocabulary for some of the common places or locations that you might need or want while traveling in Italy.

banca (bank)

città (city)

il consolato Americano (American consulate)

il ristorante (restaurant)

in campagna (in the country)

in città (in the city)

in montagna (in the mountains)

l‘albergo (hotel)

l‘ospedale (hospital)

la casa (house)

la polizia (police)

la stazione dei treni (train station)

metropolitana (subway)

museo (museum)

negozio (store)

paese (country)

spiaggia (beach)

stato (state)

ufficio (office)

Some Italian Phrases:

| English Phrases |

Italian Phrases |

| English Greetings |

Italian Greetings: |

| Hi! |

Ciao! |

|

| Good morning! |

Buongiorno! |

|

| Good evening! |

Buona sera! |

|

| Welcome! (to greet someone) |

Benvenuto!/ Benvenuta! (female) |

|

| How are you? |

Come stai?/ Come state (polite)? |

|

| I’m fine, thanks! |

Bene, grazie! |

|

| And you? |

e tu? e lei? (polite) |

|

| Good/ So-So. |

Bene/ così e così. |

|

| Thank you (very much)! |

Grazie! / (Molte grazie)! |

|

| You’re welcome! (for “thank you”) |

Prego! |

|

| Hey! Friend! |

Ciao! Amico! |

|

| I missed you so much! |

Mi sei mancato molto! |

|

| What’s new? |

Cosa c’è di nuovo? |

|

| Nothing much |

Non molto |

|

| Good night! |

Buona notte! |

|

| See you later! |

A dopo |

|

| Good bye! |

Arrivederci! |

|

| Asking for Help and Directions |

|

| I’m lost |

Mi sono perso/ persa (feminine) |

|

| Can I help you? |

Posso aiutarti?/ posso aiutarla (polite)? |

|

| Can you help me? |

Potresti aiutarmi?/ potrebbe aiutarmi? (polite) |

|

| Where is the (bathroom/ pharmacy)? |

Dove posso trovare (il bagno/ la farmacia?) |

|

| Go straight! then turn left/ right! |

Vada dritto! e poi giri a destra/ sinistra! |

|

| I’m looking for john. |

Sto cercando John. |

|

| One moment please! |

Un momento prego! |

|

| Hold on please! (phone) |

Attenda prego! |

|

| How much is this? |

Quanto costa questo? |

|

| Excuse me …! (to ask for something) |

Scusami!/ Mi scusi! (polite) |

|

| Excuse me! ( to pass by) |

Permesso |

|

| Come with me! |

Vieni con me!/ Venga con me! (polite) |

|

How to Make Small Talk in Italian

Making small talk in Italian is just the same as in English. Touch on familiar topics like jobs, sports, children — just say it in Italian! Small talk describes the brief conversations that you have with people you don’t know well.

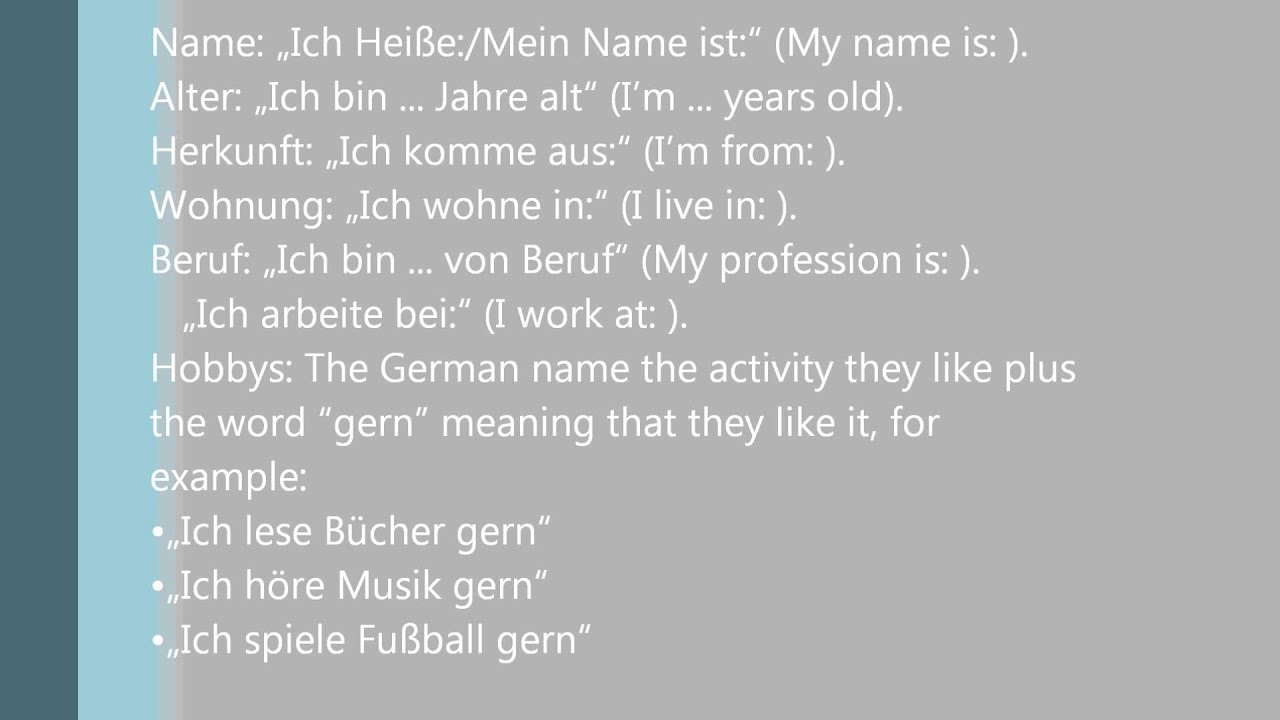

Small talk generally consists of greetings and introductions and descriptions of personal information and interests.

Greetings and introductions

Although the Italians are often more formal than we are in America, you don’t need to wait around to be introduced to someone. Take the initiative to walk up to someone and say hello.

The most common ways to greet someone is to simply say hello (Salve orBuon giorno). The following phrases are all you need to get a conversation started.

- Mi chiamo . . . (My name is . . .)

- Lei come si chiama? (What’s your name? [Formal])

- Permette che mi presenti mia moglie, Fabiana? (May I introduce my wife, Fabiana?).

Greetings and introductions are usually accompanied by a Come sta? (How are you? [Formal]) There are many possible responses, but the most common would be to say I’m doing well (Sto bene!) or I’m so-so (Così così.).

Personal information

After the necessary introductions, small talk is really just a question of sharing information about yourself and asking the other person questions about themselves. The following phrases will come in handy when you’re chitchatting with someone new.

- Sono degli . . . (I am from . . .)

- Di dov’è Lei? (Where are you from?)

- Che lavoro fa? (What is your profession?)

- Quanti anni hai? (How old are you?)

- Dove vite? (Where do you live?)

- Sono uno studente/ studentessa. [M/F] (I’m a student.)

- Sono insegnante. [M]/Faccio l’insegnate. [F] (I’m a teacher.)

- Sei sposato? [M]/Sei sposata? [F] (Are you married?)

- Hai dei figli? [Informal] (Do you have any children?)

- Ho tre figli. (I have three children.)

- Sono uno studente. [M]/Sono una studentessa. [F] (I’m a student.)

Remember to use the formal Lei version of you when meeting someone for the first time.

Italian Nouns

All Italian nouns are masculine or feminine in gender.

With very few exceptions, nouns which end in -o, -ore, a consonant, or a consonant followed by

-one, are masculine. The names of the days of the week (except Sunday), lakes, months, oceans, rivers, seas, sport teams, and names which denote males are masculine. Words imported from other languages are regarded as masculine regardless of their spelling.

With a few exceptions, singular nouns which end in -a, -à, -essa, -i, -ie, -ione, -tà, -trice, or -tù

are feminine. The names of cities, continents, fruits, islands, letters of the alphabet, states, and names which denote females are feminine.

In Italian grammar, if a word refers to a group of people, the masculine form is used:

bambini children

amici friends

In a some cases, the gender of a noun is determined by its article. For example, uno studente to denote a male student, or una studente to denote a female student. All words which end in

–nte or -ista are treated in this way.

un cliente a male client una cliente a female client

un pianista a male pianist una pianista a female pianist

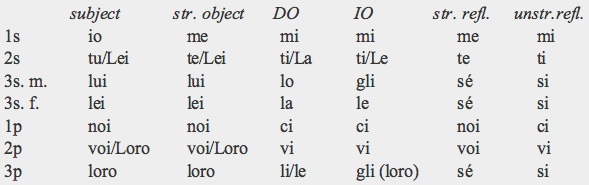

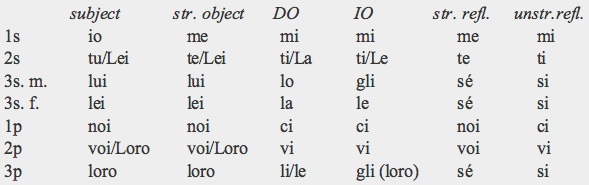

Italian Pronouns

Pronouns are words that are used in place of a noun. They can stand in for the subject,

Io mangio (

I eat), the object, Paola

mi ama (Paola loves

me), or the complement, Io vivo per

lei (I live for

her). There are many kinds of pronouns in Italian grammar, including personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, and indefinite.

Io mangio I eat

Paola mi ama Paola loves me

Io vivo per lei I live for her

Italian Verbs

Verbs are the core of the Italian language, and they refer to an action (andare

– to go; mangiare – to eat) or to a state (essere – to be; stare – to stay; esistere – to exist). In Italian grammar, there are three classes of verbs, five moods, and 21 verb tenses.

Here are some common verbs to get you started:

Andare to go

Mangiare to eat

Essere to be

Stare to stay

Esistere to exist

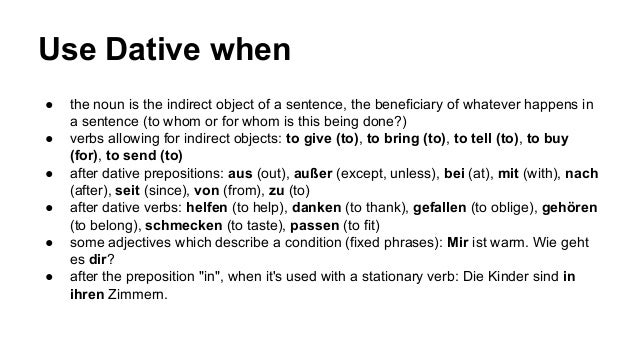

Italian Prepositions

Prepositions are words that show position in relation to space or time, or that introduce a complement. Some prepositions that are important to know in Italian are listed below:

Preposition Italian English

di: La casa di Paola Paola’s house

a: Io vado a casa I go (to) home

da: Il treno viene da Milano The train comes from Milan

in: La mamma è in Italia The mother is in Italy

con: Io vivo con Paola I live with Paola

su: La penna è sul tavolo The pen is on the table

per: Il regalo è per te The gift is for you

Italian Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that link to other words or groups of words, and common ones in Italian grammar include e- (“and”), ma (“but”), and se (“if”).

Il cane

e il gatto The dog

and the cat

Sono stanco,

ma vengo I am tired,

but I come

Se vuoi, puoi dormire qui

If you want, you can sleep here

The Auxiliary Verbs: Essere and Avere

Essere:

io sono I am

tu sei you are

lui/lei/Lei è he/she is

noi siamo we are

voi siete you are

loro sono they are

Avere:

io ho I have

tu hai you have

lui/lei/Lei ha he/ she has

noi abbiamo we have

voi avete you have

loro hanno they have

Italian Subject Pronouns / Pronomi personali

| io |

ee-oh |

I |

noi |

noy |

we |

| tu |

too |

you (informal singular) |

voi |

voy |

you (informal plural) |

| lui, lei |

lwee/lay |

he, she |

loro |

loh-roh |

they |

| Lei |

lay |

you (formal singular) |

Loro |

loh-roh |

you (formal plural) |

The

Lei form is generally used for you (singular), instead of tu, unless you’re referring to kids or animals. Loro can also mean you, but only in very polite situations. If you need to specify an inanimate object as “it” you can use

esso (masculine noun) and

essa (feminine noun), but since subject pronouns are not commonly used in Italian, these words are somewhat rare.

Personal pronouns are the only part of the sentence in which Italian makes a distinction between masculine/feminine and neuter. Neuter gender is used for objects, plants and animals except man.

How to Conjugate Italian Verbs in the Present Indicative Tense

In Italian, the present indicative tense works much like the present tense in English. To conjugate Italian verbs in the present indicative tense, you first need to understand that Italian infinitives (the “to” form, as in

to die, to sleep, to dream) end in one of three ways — and that you conjugate the verb based on that ending:

- Verbs that end in -are

- Verbs that end in -ere

- Verbs that end in -ire The endings of regular verbs don’t change. Master the endings for each mode and tense, and you’re good to go! Keep in mind that verbs agree with subjects and subject pronouns (io, tu, lui/lei/Lei, noi, voi, loro/Loro):

| Common Regular Italian Verbs in the Present Indicative Tense |

| Subject Pronoun |

Lavorare (to work) |

Prendere (to take; to order) |

Partire (to leave) |

Capire (to understand) |

| io |

lavoro |

prendo |

parto |

capisco |

| tu |

lavori |

prendi |

parti |

capisci |

| lui/lei/Lei |

lavora |

prende |

parte |

capisce |

| noi |

lavoriamo |

prendiamo |

partiamo |

capiamo |

| voi |

lavorate |

prendete |

partite |

capite |

| loro/Loro |

lavorano |

prendono |

partono |

capiscono |

Unfortunately, there are also

irregular verbs, which you have to memorize. You’ll find that the more you practice them, the easier it is to use them in conversation:

| Common Irregular Italian Verbs in the Present Indicative Tense |

| Subject Pronoun |

Andare (to go) |

Bere (to drink) |

Dare (to give) |

Fare (to do) |

Stare (to stay) |

Venire (to come) |

| io |

vado |

bevo |

do |

faccio |

sto |

vengo |

| tu |

vai |

bevi |

dai |

fai |

stai |

vieni |

| lui/lei/Lei |

va |

beve |

dà |

fa |

sta |

viene |

| noi |

andiamo |

beviamo |

diamo |

facciamo |

stiamo |

veniamo |

| voi |

andate |

bevete |

date |

fate |

state |

venite |

| loro/Loro |

vanno |

bevono |

danno |

fanno |

stanno |

vengono |

Italian Subject Pronouns and Object Pronouns:

DIRECT OBJECT PRONOUNS

DIRECT OBJECT PRONOUNS

A direct object is the direct recipient of the action of a verb. Direct object pronouns replace direct object nouns. In Italian the forms of the direct object pronouns (i pronomi diretti) are as follows:

| Person |

Singular |

Plural |

|

| 1st. person |

mi » me |

ci » us |

| 2nd. person familiar |

ti » you |

vi » you |

| 2nd. person polite* |

La » you (m. and f.) |

Li » You (m.) |

| Le » You (f.) |

| 3rd. person |

lo » him, it |

li » them (m.) |

| la » her it |

le » them (f.) |

These pronouns are used as follows:

- They stand immediately before th

e verb or the auxiliary verb in the compound tenses. Examples:

e verb or the auxiliary verb in the compound tenses. Examples:

- Li ho invitati a cena » I have invited them to dinner

- L’ho veduta ieri » I saw her yesterday

- Ci hanno guardati e ci hanno seguiti » They watched us and followed us

In a negative sentence, the word non must come before the object pronoun.

- Non la mangia » He doesn’t eat it

- Perchè non li inviti? » Why don’t you invite them?

- The object pronoun is attached to the end of an infinitive. Note that the final –e of the infinitive is dropped.

- È importante mangiarla ogni giorno » It is important to eat it every day

- Volevo comprarla » I wanted to buy it

- The Object pronouns are attached to ecco to express here I am, here you are, here he is, and so on.

- Dov’è la signorina? – Eccola! » Where is the young woman? – Here she is!

- Hai trovato le chiavi? – Sì, eccole! » Have you found the keys? – Yes, here they are!

- The pronouns lo and la are often shortened to l’.

(*) Note that second person polite form pronouns are capitalized.

Holiday Phrases:

| Buon Anno! |

Happy New Year! |

| Buona Pasqua! |

Happy Easter! |

| Buon compleanno! |

Happy Birthday! |

| Buon Natale! |

Merry Christmas! |

| Buone feste! |

Happy Holidays! |

| Buona vacanza! |

Have a good vacation! |

| Buon divertimento! |

Have a good time! |

| Buon viaggio! |

Have a good trip! |

| Tanti auguri! |

Best wishes! |

Babbo Natale is Santa Claus and

il panettone or

il pandoro are the traditional cakes eaten at Christmas. For Easter, the traditional cake is called

la colomba. Be careful with the difference between ferie and feriale:

le ferie or

i giorni di ferie are holidays when most places of business are closed; the opposite is

un giorno feriale, or a weekday/working day.

INDIRECT OBJECT PRONOUNS

While direct object pronouns answer the question what? or whom? Indirect object pronouns answer the question to whom? or for whom? Also, they’re the same as the Direct Object Pronouns except for the pronouns in the Third Person (i.e. to him; to her; to them).

| Singolare |

Singular |

|

Plurale |

Plural |

| mi |

(to/for) me |

|

ci |

(to/for) us |

| ti |

(to/for) you (informal) |

|

vi |

(to/for) you (informal) |

| gli |

(to/for) him, it |

|

loro |

(to/for) them (m. & f.) |

| le |

(to/for) her, it |

|

|

|

| Le |

(to/for) you (formal f. & m.) |

|

Loro |

(to/for) you (formal f. & m.) |

The direct object is governed directly by the verb, for example, in the following statement: Romeo loved her.

The Indirect Object in an English sentence often stands where you would expect the direct object but common sense will tell you that the direct object is later in the sentence, e.g.: Romeo bought her a bunch of flowers.

The direct object — i.e. the thing that Romeo bought is “a bunch of flowers”; Romeo didn’t buy “her” as if she were a slave. So the pronoun her in the sentence actually means “for her” and is the Indirect Object.

Examples:

» Qulacuno mi ha mandato una cartolina dalla Spagna

Someone (has) sent me a postcard from Spain.

» Il professore le ha spiegato il problema

The teacher (has) explained the problem to her.

» Voglio telefonargli

I want to phone him.

» Il signor Brambilla ci ha insegnato l’italiano

Mr Brambilla taught us Italian.

» Cosa gli dici?

What are you saying to him/to them?

» Lucia,tuo padre vuole parlarti!

Lucia, your father wants to speak to you!

» Non gli ho mai chiesto di aiutarmi

I (have) never asked him to help me.

» Non oserei consigliarti

I would not dare to advise you

» Le ho regalato un paio di orecchini

I gave her a present of a pair of earrings

Useful Words in Italian:

| and |

e |

eh |

always |

sempre |

sehm-preh |

| or |

o |

oh |

often |

spesso |

speh-soh |

| but |

ma |

mah |

sometimes |

qualche volta |

kwal-keh vohl-tah |

| not |

non |

nohn |

usually |

usualmente |

oo-zoo-al-mehn-teh |

| while |

mentre |

mehn-treh |

especially |

specialmente |

speh-chee-al-mehn-teh |

| if |

se |

seh |

except |

eccetto |

eh-cheh-toh |

| because |

perché |

pehr-kay |

book |

il libro |

lee-broh |

| very, a lot |

molto |

mohl-toh |

pencil |

la matita |

mah-tee-tah |

| also, too |

anche |

ahn-keh |

pen |

la penna |

pehn-nah |

| although |

benché |

behn-keh |

paper |

la carta |

kar-tah |

| now |

adesso, ora |

ah-deh-so, oh-rah |

dog |

il cane |

kah-neh |

| perhaps, maybe |

forse |

for-seh |

cat |

il gatto |

gah-toh |

| then |

allora, poi |

ahl-loh-rah, poy |

friend (fem) |

l’amica |

ah-mee-kah |

| there is |

c’è |

cheh |

friend (masc) |

l’amico |

ah-mee-koh |

| there are |

ci sono |

chee soh-noh |

woman |

la donna |

dohn-nah |

| there was |

c’era |

che-rah |

man |

l’uomo |

woh-moh |

| there were |

c’erano |

che-rah-no |

girl |

la ragazza |

rah-gat-sah |

| here is |

ecco |

ehk-koh |

boy |

il ragazzo |

rah-gat-soh |

Question Words in Italian:

| Who |

Chi |

kee |

| Whose |

Di chi |

dee kee |

| What |

Che cosa |

keh koh-sah |

| Why |

Perché |

pehr-keh |

| When |

Quando |

kwahn-doh |

| Where |

Dove |

doh-veh |

| How |

Come |

koh-meh |

| How much |

Quanto |

kwahn-toh |

| Which |

Quale |

kwah-leh |

Days of the week:

| Monday |

lunedì |

loo-neh-dee |

| Tuesday |

martedì |

mahr-teh-dee |

| Wednesday |

mercoledì |

mehr-koh-leh-dee |

| Thursday |

giovedì |

zhoh-veh-dee |

| Friday |

venerdì |

veh-nehr-dee |

| Saturday |

sabato |

sah-bah-toh |

| Sunday |

domenica |

doh-men-ee-kah |

| yesterday |

ieri |

yer-ee |

| day before yesterday |

avantieri / l’altroieri (m) |

ah-vahn-tyee-ree |

| last night |

ieri sera |

yer-ee seh-rah |

| today |

oggi |

ohd-jee |

| tomorrow |

domani |

doh-mahn-ee |

| day after tomorrow |

dopodomani |

doh-poh-doh-mahn-ee |

| day |

il giorno |

eel zhor-noh |

To say

on Mondays, on Tuesdays, etc., use

il before

lunedì through

sabato, and

la before

domenica.

Months of the year:

| January |

gennaio |

jehn-nah-yoh |

| February |

febbraio |

fehb-brah-yoh |

| March |

marzo |

mar-tsoh |

| April |

aprile |

ah-pree-leh |

| May |

maggio |

mahd-joh |

| June |

giugno |

joo-nyoh |

| July |

luglio |

loo-lyoh |

| August |

agosto |

ah-goh-stoh |

| September |

settembre |

seht-tehm-breh |

| October |

ottobre |

oht-toh-breh |

| November |

novembre |

noh-vehm-breh |

| December |

dicembre |

dee-chem-breh |

| week |

la settimana |

lah sett-ee-mah-nah |

| month |

il mese |

eel meh-zeh |

| year |

l’anno |

lahn-noh |

Days and months are

not capitalized

. To express the date, use

È il (number) (month). May 5th would be

È il 5 (or

cinque) maggio. But for the first of the month, use

primo instead of 1 or uno. To express

ago, as in

two days ago, a month ago, etc., just add

fa afterwards. To express

last, as in

last Wednesday, last week, etc., just add

scorso (for masculine words) or

scorsa (for feminine words) afterwards.

una settimana fa – a week ago

la settimana scorsa – last week

un mese fa – a month ago

l’anno scorso – last year

Possessive Pronouns:

| Maschile singolare |

Maschile plurale |

Femminile singolare |

Femminile plurale |

| il mio

il tuo

il suo

il nostro

il vostro

il loro |

i miei

i tuoi

i suoi

i nostri

i vostri

i loro |

la mia

la tua

la sua

la nostra

la vostra

la loro |

le mie

le tue

le sue

le nostre

le vostre

le loro |

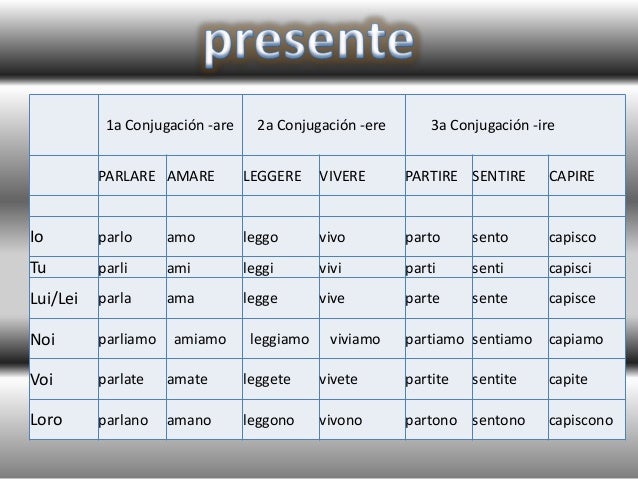

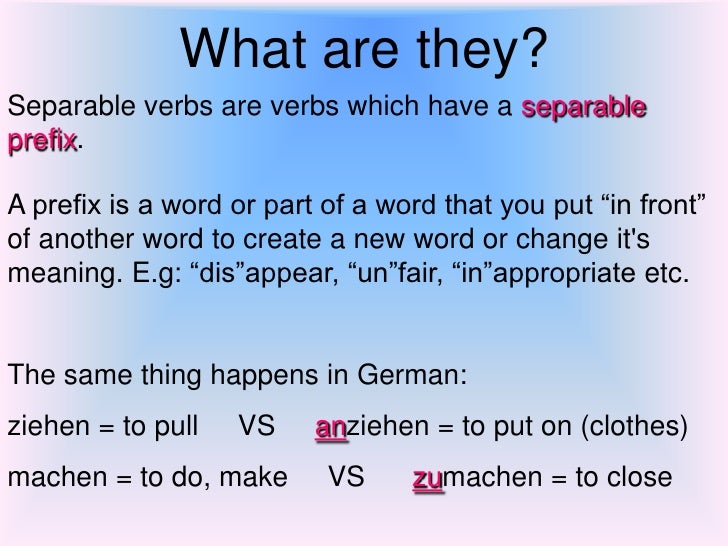

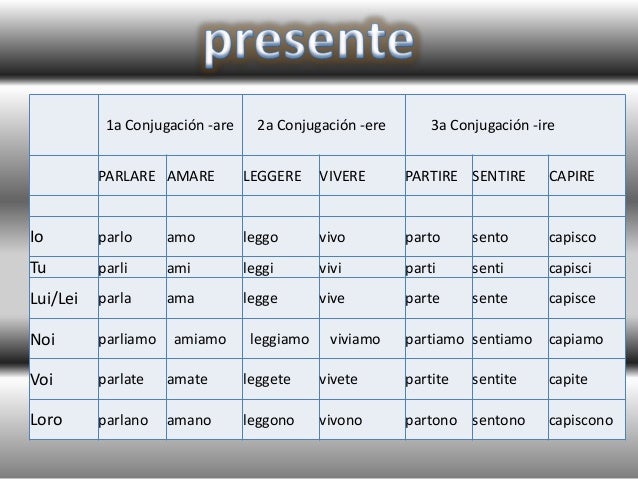

Italian Grammar Lessons: The Three Groups Of Regular Verbs

This lesson is about the three groups of Italian regular verbs.

All Italian regular verbs can be divided into three groups, as classified according to the ending of their infinitive forms.

Verbs in the first group or first conjugation end in – are, such as abitare, mangiare or lavare.

Abitare – to live

io abito

tu abiti

lui/lei/Lei abita

noi abitiamo

voi abitate

loro/Loro abitano

Verbs in the second group or second conjugation end in – ere, such as perdere and correre.

Perdere – to lose

io perdo

tu perdi

lui/lei/Lei perde

noi perdiamo

voi perdete

loro/Loro perdono

Verbs in the third group or third conjugation end in – ire, such as dormire and aprire. The main characteristic of the third group is that some verbs, such as preferire, add the suffix –isc between the root and the declination.

Dormire – to sleep

io dormo

tu dormi

lui/lei/Lei dorme

noi dormiamo

voi dormite

loro/Loro dormono

Preferire – to prefer

io preferisco

tu preferisci

lui/lei/Lei preferisce

noi preferiamo

voi preferite

loro/Loro preferiscono

It’s important to learn the conjugations for these three groups as early as you can!

Italian Grammar Lessons: Reflexive Verbs

This lesson is about reflexive verbs!

A reflexive verb is used when the subject and object of the verb are the same. For example, “kill yourself”.

Reflexive verbs are more common in Italian than in English – verbs which in English are too “obvious” to be used in the reflexive form (wake up, get up, wash, clean your teeth, and so on..) do need the reflexive form in Italian.

So, for example, in Italian you might “suicide yourself”, absurd as it sounds in English!

Many Italian verbs have reflexive forms. You can recognise them because they end in “-si”. For example:

alzarsi (get yourself up)

svegliarsi (wake yourself up)

vestirsi (dress yourself)

lavarsi (wash yourself)

riposarsi (rest yourself)

mettersi (put yourself)

fermarsi (stop yourself)

sedersi (sit yourself)

When you use a reflexive verb you have to put the correct reflexive pronoun before the verbs.

The reflexive pronouns are:

io – mi

tu – ti

lui/lei/Lei – si

noi – ci

voi – vi

loro – si

Here are two examples of the conjugation of reflexive verbs in Italian:

svegliarsi – to wake yourself up

(io) mi sveglio

(tu) ti svegli

(lui/lei/Lei) si sveglia

(noi) ci svegliamo

(voi) vi svegliate

(loro/Loro) si svegliano

alzarsi – to get yourself up

(io) mi alzo

(tu) ti alzi

(lui/lei/Lei) si alza

(noi) ci alziamo

(voi) vi alzate

(loro/Loro) si alzano

Modal verbs

Italian modal verbs are called “

VERBI SERVILI“. They have irregular forms. They are:

POTERE (can)

VOLERE (to want, to wish, to need)

DOVERE (must, to have to, ought to, should)

Watch the following examples:

1. Mi

puoi telefonare domani? (

Can you call me tomorrow?)

2.

Voglio andare a Roma (I want to go to Rome)

3. Aspettami,

devo parlar

ti (Wait, I

have to talk to you!)

Modal verbs work as a support to other verbs and indicate possibility, will, need and duty.

Verb

SAPERE (can) becomes a modal verb when it means “ESSERE CAPACE DI” “to be able to”.

example:

So suonare il piano (I

can play the piano)

Modal verbs can be used with

atonic personal pronouns that can stand before the modal verb( 1.) or after the infinitive (3.)

Modal verbs are directly added to the infinitive of a verb without any

prepositions.

POTERE can be used:

– with the meaning of

“forse” (=perhaps, maybe): “Posso essermi sbagliato, ma non so esattamente” (=I could be wrong, but I don’t know exactly)

– as a permission (may I?) : Posso uscire? (May I go out?)

– as a capability: Quest’anno possiamo vincere il campionato (This year we can win the championship)

– in the polite form: Potresti prestarmi il tuo libro? (Could you lend me your book?)

DOVERE can be used:

– with the meaning of probability: Deve essergli successo un incidente (He must have had an accident)

– as an obligation, a need: Se vuoi migliorare il tuo italiano,

devi fare i compiti. ( If you want to improve your italian, you

must do your homework)

Modal Verbs – Present Tense

- Io posso

- Tu puoi

- Egli può

- Noi possiamo

- Voi potete

- Essi possono

- Io voglio

- Tu vuoi

- Egli/ella vuole

- Noi vogliamo

- Voi volete

- Essi vogliono

- Io devo

- Tu devi

- Egli/ella deve

- Noi dobbiamo

- Voi dovete

- Essi devono

In Italian as in English these modals verbs (

verbi servili) are easy to identify. Modal verbs in Italian indicate a “must,” “capability” or a “wish.”

These words can be used alone, as in “

Vorrei una pizza” (“I’d like a pizza”), or as

modal verbs in conjunction with another verb in the infinitive tense. For example, “

Vorrei camminare un pò di più” (“I’d like to walk a little bit more.”) “

Volere” for instance can be used with nouns and infinitives (“

Voglio partire” or “

Voglio una pizza.”) “

Potere” and “

dovere” can be used with infinitives only (“

Non posso lavorare” or “

Devomangiare ora.”)

In the negative form you have only to put only NON in front of the modal:

- Non puoi capire

- Non devi partire

- Non vuoi lasciarmi vero?

With the compound tenses, the modal verbs take the auxiliary plus the infinitive that follows. For example:

- Claudio HA DOVUTO lasciare il suo lavoro. (dovere richiede AVERE)

- Maria HA DOVUTO studiare. (studiare richiede AVERE)

- Maria E’ DOVUTA uscire (uscire richiede essere)

- Maria HA POTUTO parlare con lui (potere richiede avere)

- Maria E’ POTUTA venire alla festa (venire richiede essere)

- Maria HA VOLUTO mangiare (mangiare richiede volere)

- Maria E’ VOLUTA VENIRE al cinema con me (venire richiede essere)

The auxiliary verb “to be” is used in the following examples:

- Compound tenses and with many intransitive verbs like “sono partita“, “mio fratello è uscito.”

- With impersonal verbs: piove (it’s raining), fa freddo (it’s cold), fa caldo (it’s warm)

- With reflexive verbs: “Maria si è lavata le mani e si è messa il tovagliolo prima di mangiare.” (“Maria washed her hands and put out the table cloth before eating.”)

| volere – to want (to) |

potere – to be able to |

dovere – to have to |

| io voglio |

io posso |

io devo |

| tu vuoi |

tu puoi |

tu devi |

| Lei vuole |

Lei puo’ |

Lei deve |

| lui/lei vuole |

lui/lei puo’ |

lui/lei deve |

| noi vogliamo |

noi possiamo |

noi dobbiamo |

| voi volete |

voi potete |

voi dovete |

| loro vogliono |

loro possono |

loro devono |

Volere can be used with nouns and infinitives (dictionary form). Voglio una birra. Voglio mangiare.

Potere and dovere are used with infinitives only. Non posso studiare. Devo uscire.

To negate a modal (to say you don’t want to, can’t or must not), just put non in front of it.

Italian Articles

In Italian grammar, articles identify the gender and the number of the nouns, and they are essential in order to recognize irregular nouns. Articles can be masculine or feminine, singular or plural and, except in some specific cases, they must always be used. The article serves to define the noun associated with it, and with which it must agree in gender and number.

Definitive articles

In Italian, we put the article before the noun, just like in English. However, in English, the definite article is only one – the. In Italian, when the noun is masculine, there are three types of articles in the singular, and two types in the plural. For feminine nouns, there are two different articles for the singular, and one for the plural. Let’s take a look!

Masculine Articles Feminine Articles

Singular Il Lo L’ La L’

Plural I Gli Gli Le Le

Now, let’s break down when to use which definitive article in Italian!

With masculine articles:

Il is used before a noun that begins with a consonant, except“s + consonant, ps, gn, z, y, and z. Examples: Il ragazzo, il libro, il vino.

I is the plural form of il. If you use il in singular, you have to use I in plural.

Examples: I ragazzi, i libri, i vini.

Lo is used before a noun that begins with s + consonant, ps, gn,z,y, and z.

Examples: Lo studente, lo sport, lo psicologo, lo yogurt.

Gli is the plural form of lo. If you use lo in singular, you have to use gli in plural. Examples:

Gli studenti, gli sport, gli psicologi, gli yogurt.

L’ is used before a noun that begins with a vowel or with h; in Italian grammar, h is silent. Examples: L’ orologio, l’amico, l’ufficio, l’hotel.

Gli is used for the plural form when l’ is used in the singular:

Gli orologi, gli amici, gli uffici, gli hotel.

Now, let’s go over when to use feminine definite articles.

La is used before a noun that begins with a consonant:

La casa, la ragazza, la bottiglia.

L’ is used before a noun that begins with a vowel: L’amica, l’alice, l’onda, l’aspirina.

Le is used with all feminine words in the plural: Le case, le ragazze, le bottiglie, le amiche, le alici, le onde, le aspirine.

Indefinite Articles

Indefinite articles in Italian grammar introduce a generic or not defined noun.

The masculine indefinite articles are

un and

uno, and the feminine forms are

una and

un’ – meaning a or an.

Un is used before masculine nouns starting with vowel or consonant: un uomo, un libro.

Uno isused before masculine nouns starting with s+ consonant, z, gn, x, y, ps, pn, i+vowel, such as in uno studente.

Una is used before feminine nouns starting with consonant, such as una donna.

Un’ is used before feminine nouns starting with vowel, such as in un’automobile.

When to Use Articles

In Italian grammar, articles are used in the following cases:

Before nouns: : il gatto, la donna, l’uomo, il libro, la casa.

Before a person’s profession : il dottore, il meccanico, il professore, la professoressa.

Before a title : il signore, la signora, l’onorevole.

Before dates: il 2 giugno 1990

Before hours: sono le 3, è l’una.

Before names of nations or associations in the plural: gli Stati Uniti, le Nazioni Unite.

Before the days of the week to indicate a repeated, habitual activity: la domenica studio italiano.

Articles are

not used before nouns in the following cases:

When they want to convey a very generic feeling of something indefinite: mangio pasta (“I eat pasta”), vedo amici (“I see friends”).

Before a name: Roberto, Maria, Stefano, Alice, Roma, Milano

Before the demonstrative adjective questo (“this”), quello (“that”): questa casa (“this house,” questo libro (“this book”), quel ragazzo (“that guy”).

Before a possessive adjective followed by a singular family noun: mia madre, mio padre, mio fratello, mia sorella.

With days of the week: domenica vado in montagna (“I am going to the mountains on Sunday”).

Italian Grammar Lessons: prepositions, ‘a’ or ‘in’?

This lesson is about the different use of the prepositions ‘a’ and ‘in’ in Italian grammar.

Let’s start with the preposition ‘a’, which means ‘to’ (movement) or ‘in’ if it indicates location (cities and places).

Examples:

Tu dai la penna a Simona. (You give the pen to Simona.)

Sono a casa. (I’m at home.)

Abito a Roma, ma ora sono a Venezia. (I live in Rome, but now I’m in Venice.)

We generally use the preposition ‘a’ with the infinite form of the verbs and with names of cities and minor islands.

Examples:

Vado a mangiare fuori stasera. (I will eat out this evening.)

Torno a Madrid per Natale. (I will go back to Madrid for Christmas.)

As regard the preposition ‘in’, we use it with the names of continents, states, nations, regions, larger islands, and with words ending in “-eria”.

Examples:

In Inghilterra bevi tè tutti i giorni. (In England you drink tea every day.)

Bologna si trova in Emilia-Romagna. (Bologna is in Emilia-Romagna.)

Di solito compro i libri in quella libreria. (I usually buy books in that bookshop.)

Here are a few of the nouns before which we use the preposition ‘in’:

banca (bank) , biblioteca (library), classe (class), città (city), chiesa (church), campagna (country), piscina (pool), ufficio (office), albergo (hotel), farmacia (pharmacy)

Careful!

When talking about someone’s house or place of work, you use the preposition ‘da’ plus the name of the owner.

Examples:

Sono dal dottore. (I’m at the Doctor’s office.)

Vado da Sara per il weekend. (I’m going to Sara’s place for the weekend.)

Italian Grammar Lessons: There is/are – C’è / ci sono

This lesson is about the use of “

c’è / ci sono“, which would translate into English as ‘there is/are’.

The word “ci” is used as a pronoun referring to previously mentioned places and things in order not to repeat them.

Examples:

Quando vai al supermercato? (When are you going to the supermarket?)

Ci vado domani (I will go there tomorrow)

Ci = al supermercato (at the supermarket)

“C’è” is the short form of “ci è”, while “ci sono” is the plural form and they state the presence or existence of someone or something.

Examples:

C’è troppo zucchero nel mio caffè. (There is too much sugar in my coffee.)

Ci sono molti negozi a Milano. (There are a lot of shops in Milan.)

Ci sono molte ragioni per partire. (There are many reasons to leave.)

C’è qualcuno in cucina? (Is there someone in the kitchen?)

To express negation, you just need to put the particle NON before “c’è / ci sono”.

Examples:

Non c’è nessuno in cucina. (There isn’t anyone in the kitchen.)

Non ci sono penne nell’astuccio. (There aren’t any pens in the pencil case.)

Back to Italian lesson on: there is / are – c’è / ci sono

Italian Grammar Lessons: Plurals

This lesson will show you how to create the plural form of Italian nouns.

It’s important to know the gender of the word (masculine or feminine) and you can usually work this out by looking at the vowel it ends with.

To turn a singular word into a plural one, you usually only need to change the final vowel, though there are of course plenty of exceptions!

Singular nouns ending in “-o” are usually masculine. To produce a plural you need to change this ending to “

-i“,

Examples:

il cavall

o → i cavall

i (the horse – the horses)

il tavol

o → i tavol

i (the table – the tables)

Nouns ending in “-a” are usually feminine. To create the plural form you need to change the final vowel to “

-e“.

Examples:

la carot

a → le carot

e (the carrot – the carrots)

la sedi

a → le sedi

e (the chair – the chairs)

But some nouns ending in “-a” are masculine, in which case the plural is “

-i“.

Examples:

il problem

a → i problem

i (the problem – the problems)

il poet

a → i poet

i (the poet – the poets)

And similarly some nouns ending in “-o” are feminine and their plural is the same as the singular form.

Examples:

la radi

o → le radi

o (the radio – the radios)

la fot

o → le fot

o (the photo – the photos)

Club member Ida writes:

Words like ‘la radio’, ‘la foto’, ‘la moto’ or ‘la auto’ do not change in the plural because they are truncated versions of the original words ‘la radiotelefonia’, ‘la fotografia’, ‘la motocicletta’ and ‘l’automobile’. Truncated words do not change in the plural.

Instead “la mano” which is a true feminine word that ends in “o” has the regular plural “le mani” following the rules for forming the plural.

The plural form of singular nouns ending in “-ista” can be either “-i” (if masculine) or “-e” (if feminine).

Examples:

l’art

ista → gli art

isti / le art

iste (the artist – the artists (m) / the artists (f))

il dentista → i dentisti / le dentiste (the dentist – the dentists)

Some nouns have just one form which works both for the singular and for the plural. A good example is the various nouns which end with an accented vowel.

Examples:

la citt

à → le citt

à (the city – the cities)

la virt

ù → le virt

ù (the virtue – the virtues)

il pap

à → i pap

à (the dad – the dads)

Nouns ending in consonants (which are often borrowed ‘foreign’ words) also have identical singular and plural forms.

Examples:

il computer → i computer (the computer – the computers)

lo yogurt → gli yogurt (the yogurt – the yogurts)

There are some cases in which plural nouns have a different spelling.

Some masculine substantives ending in “-co” and “-go” form their plural with “

-chi” and “

-ghi“.

Examples:

il tedes

co → i tedes

chi (the German – the Germans)

l’alber

go → gli alber

ghi (the hotel – the hotels)

Others form the plural with “

-ci” or “

-gi“.

Examples:

l’ami

co → gli ami

ci (the friend – the friends)

l’archeolo

go → gli archeolo

gi (the archaeologist – the archaeologists).

Feminine nouns ending in “-ca” and “-ga” follow the same rule.

Examples:

la tas

ca → le tas

che (the pocket – the pockets)

l’al

ga → le al

ghe (the seaweed – the seaweeds)

Italian Grammar Lessons: Like – Piace/Piacciono

The verb “piacere” (to like) in Italian has an unusual construction, in the sense that the subject of the action is reversed.

The meaning of “piacere” is best thought of as “to please, to be pleasing to” rather than ‘to like’.

In English you ‘like’ something or doing something. In Italian it’s the object or activity that ‘pleases’ you.

To construct this grammatically, we need to use indirect pronouns. For example:

Mi piace la pizza (‘I like pizza’, but literally: ‘Pizza pleases me.’)

Here’s the same example sentence conjugated for the different subjects:

Mi piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases me.’)

Ti piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases you.’)

Gli piace la pasta. (‘Pizza pleases him.’)

Le piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases her.’)

Ci piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases us.’)

Vi piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases you.’)

Gli piace la pizza. (‘Pizza pleases them.’)

A further complication is that, if the subject of the sentence is plural, you need to remember to change the verb from the third person singular (‘piace’) to the third person plural (‘piacciono’).

For example:

Mi piacciono i biscotti. (‘Biscuits please me.’)

The negative is formed by adding ‘non’. For example:

Non gli piace il cioccolato. (‘Chocolate doesn’t please him.’)

Non ci piacciono le lasagne. (‘Lasagnes don’t please us.’)

The verb ‘piacere’ can also be followed by another verb, which has to be in the infinitive form. For example:

Mi piace leggere. (‘Reading pleases me.’)

Non gli piace studiare. (‘Studying doesn’t please him.’)

Ci piace mangiare al ristorante. (‘Eating at the restaurant pleases us.’)

Il presente: -are verbs

| 1. ABITARE : |

to live |

| Io: |

abito |

Noi: |

abitiamo |

| Tu: |

abiti |

Voi: |

abitate |

| Lui: |

abita |

Loro: |

abitano |

|

| 2. ARRIVARE : |

to arrive |

| Io: |

arrivo |

Noi: |

arriviamo |

| Tu: |

arrivi |

Voi: |

arrivate |

| Lui: |

arriva |

Loro: |

arrivano |

|

| 3. ASPETTARE : |

to wait for |

| Io: |

aspetto |

Noi: |

aspettiamo |

| Tu: |

aspetti |

Voi: |

aspettate |

| Lui: |

aspetta |

Loro: |

aspettano |

|

| 4. CAMMINARE : |

to walk |

| Io: |

cammino |

Noi: |

camminiamo |

| Tu: |

cammini |

Voi: |

camminate |

| Lui: |

cammina |

Loro: |

camminano |

|

| 5. COMINCIARE : |

to begin |

| Io: |

comincio |

Noi: |

cominciamo |

| Tu: |

cominci |

Voi: |

cominciate |

| Lui: |

comincia |

Loro: |

cominciano |

|

| 6. CUCINARE : |

to cook |

| Io: |

cucino |

Noi: |

cuciniamo |

| Tu: |

cucini |

Voi: |

cucinate |

| Lui: |

cucina |

Loro: |

cucinano |

|

| 7. GUARDARE : |

to watch |

| Io: |

guardo |

Noi: |

guardiamo |

| Tu: |

guardi |

Voi: |

guardate |

| Lui: |

guarda |

Loro: |

guardano |

|

| 8. IMPARARE : |

to learn |

| Io: |

imparo |

Noi: |

impariamo |

| Tu: |

impari |

Voi: |

imparate |

| Lui: |

impara |

Loro: |

imparano |

|

| 9. LAVORARE : |

to work |

| Io: |

lavoro |

Noi: |

lavoriamo |

| Tu: |

lavori |

Voi: |

lavorate |

| Lui: |

lavora |

Loro: |

lavorano |

|

| 10. MANDARE : |

to send |

| Io: |

mando |

Noi: |

mandiamo |

| Tu: |

mandi |

Voi: |

mandate |

| Lui: |

manda |

Loro: |

mandano |

|

| 11. NUOTARE : |

to swim |

| Io: |

nuoto |

Noi: |

nuotiamo |

| Tu: |

nuoti |

Voi: |

nuotate |

| Lui: |

nuota |

Loro: |

nuotano |

|

| 12. PENSARE : |

to think |

| Io: |

penso |

Noi: |

pensiamo |

| Tu: |

pensi |

Voi: |

pensate |

| Lui: |

pensa |

Loro: |

pensano |

|

| 13. PORTARE : |

to bring |

| Io: |

porto |

Noi: |

portiamo |

| Tu: |

porti |

Voi: |

portate |

| Lui: |

porta |

Loro: |

portano |

|

| 14. TORNARE : |

to return |

| Io: |

torno |

Noi: |

torniamo |

| Tu: |

torni |

Voi: |

tornate |

| Lui: |

torna |

Loro: |

tornano |

|

Il presente: -ere verbs

| 1. CADERE : |

to fall |

| Io: |

cado |

Noi: |

cadiamo |

| Tu: |

cadi |

Voi: |

cadete |

| Lui: |

cade |

Loro: |

cadono |

|

| 2. CHIEDERE : |

to ask |

| Io: |

chiedo |

Noi: |

chiediamo |

| Tu: |

chiedi |

Voi: |

chiedete |

| Lui: |

chiede |

Loro: |

chiedono |

|

| 3. CHIUDERE : |

to close |

| Io: |

chiudo |

Noi: |

chiudiamo |

| Tu: |

chiudi |

Voi: |

chiudete |

| Lui: |

chiude |

Loro: |

chiudono |

|

| 4. CREDERE : |

to believe |

| Io: |

credo |

Noi: |

crediamo |

| Tu: |

credi |

Voi: |

credete |

| Lui: |

crede |

Loro: |

credono |

|

| 5. LEGGERE : |

to read |

| Io: |

leggo |

Noi: |

leggiamo |

| Tu: |

leggi |

Voi: |

leggete |

| Lui: |

legge |

Loro: |

leggono |

|

| 6. METTERE : |

to put |

| Io: |

metto |

Noi: |

mettiamo |

| Tu: |

metti |

Voi: |

mettete |

| Lui: |

mette |

Loro: |

mettono |

|

| 7. PERDERE : |

to lose |

| Io: |

perdo |

Noi: |

perdiamo |

| Tu: |

perdi |

Voi: |

perdete |

| Lui: |

perde |

Loro: |

perdono |

|

| 8. PRENDERE : |

to take |

| Io: |

prendo |

Noi: |

prendiamo |

| Tu: |

prendi |

Voi: |

prendete |

| Lui: |

prende |

Loro: |

prendono |

|

| 9. RICEVERE : |

to receive |

| Io: |

ricevo |

Noi: |

riceviamo |

| Tu: |

ricevi |

Voi: |

ricevete |

| Lui: |

riceve |

Loro: |

ricevono |

|

| 10. RIPETERE : |

to repeat |

| Io: |

ripeto |

Noi: |

ripetiamo |

| Tu: |

ripeti |

Voi: |

ripetete |

| Lui: |

ripete |

Loro: |

ripetono |

|

| 11. RISPONDERE : |

to answer |

| Io: |

rispondo |

Noi: |

rispondiamo |

| Tu: |

rispondi |

Voi: |

rispondete |

| Lui: |

risponde |

Loro: |

rispondono |

|

| 12. SCRIVERE : |

to write |

| Io: |

scrivo |

Noi: |

scriviamo |

| Tu: |

scrivi |

Voi: |

scrivete |

| Lui: |

scrive |

Loro: |

scrivono |

|

| 13. SPENDERE : |

to spend (money) |

| Io: |

spendo |

Noi: |

spendiamo |

| Tu: |

spendi |

Voi: |

spendete |

| Lui: |

spende |

Loro: |

spendono |

|

| 14. VEDERE : |

to see |

| Io: |

vedo |

Noi: |

vediamo |

| Tu: |

vedi |

Voi: |

vedete |

| Lui: |

vede |

Loro: |

vedono |

|

| 15. VIVERE : |

to live |

| Io: |

vivo |

Noi: |

viviamo |

| Tu: |

vivi |

Voi: |

vivete |

| Lui: |

vive |

Loro: |

vivono |

|

Il presente: -ire verbs

| 1. APRIRE : |

to open |

| Io: |

apro |

Noi: |

apriamo |

| Tu: |

apri |

Voi: |

aprite |

| Lui: |

apre |

Loro: |

aprono |

|

| 2. DORMIRE : |

to sleep |

| Io: |

dormo |

Noi: |

dormiamo |

| Tu: |

dormi |

Voi: |

dormite |

| Lui: |

dorme |

Loro: |

dormono |

|

| 3. MENTIRE : |

to lie |

| Io: |

mento |

Noi: |

mentiamo |

| Tu: |

menti |

Voi: |

mentite |

| Lui: |

mente |

Loro: |

mentono |

|

| 4. OFFRIRE : |

to offer |

| Io: |

offro |

Noi: |

offriamo |

| Tu: |

offri |

Voi: |

offrite |

| Lui: |

offre |

Loro: |

offrono |

|

| 5. PARTIRE : |

to leave |

| Io: |

parto |

Noi: |

partiamo |

| Tu: |

parti |

Voi: |

partite |

| Lui: |

parte |

Loro: |

partono |

|

| 6. SEGUIRE : |

to follow |

| Io: |

seguo |

Noi: |

seguiamo |

| Tu: |

segui |

Voi: |

seguite |

| Lui: |

segue |

Loro: |

seguono |

|

| 7. SENTIRE : |

to hear |

| Io: |

sento |

Noi: |

sentiamo |

| Tu: |

senti |

Voi: |

sentite |

| Lui: |

sente |

Loro: |

sentono |

|

| 8. SERVIRE : |

to serve |

| Io: |

servo |

Noi: |

serviamo |

| Tu: |

servi |

Voi: |

servite |

| Lui: |

serve |

Loro: |

servono |

|

| 9. VESTIRE : |

to dress |

| Io: |

vesto |

Noi: |

vestiamo |

| Tu: |

vesti |

Voi: |

vestite |

| Lui: |

veste |

Loro: |

vestono |

|

Il presente: all verbs

| 1. ANDARE : |

to go |

| Io: |

vado |

Noi: |

andiamo |

| Tu: |

vai |

Voi: |

andate |

| Lui: |

va |

Loro: |

vanno |

|

| 2. AVERE : |

to have |

| Io: |

ho |

Noi: |

abbiamo |

| Tu: |

hai |

Voi: |

avete |

| Lui: |

ha |

Loro: |

hanno |

|

| 3. CONOSCERE : |

to know |

| Io: |

conosco |

Noi: |

conosciamo |

| Tu: |

conosci |

Voi: |

conoscete |

| Lui: |

conosce |

Loro: |

conoscono |

|

| 4. DARE : |

to give |

| Io: |

do |

Noi: |

diamo |

| Tu: |

dai |

Voi: |

date |

| Lui: |

dà |

Loro: |

danno |

|

| 5. DEDICARE : |

to dedicate |

| Io: |

dedico |

Noi: |

dedichiamo |

| Tu: |

dedichi |

Voi: |

dedicate |

| Lui: |

dedica |

Loro: |

dedicano |

|

| 6. DIRE : |

to say or tell |

| Io: |

dico |

Noi: |

diciamo |

| Tu: |

dici |

Voi: |

dite |

| Lui: |

dice |

Loro: |

dicono |

|

| 7. DOVERE : |

to must or have to |

| Io: |

devo |

Noi: |

dobbiamo |

| Tu: |

devi |

Voi: |

dovete |

| Lui: |

deve |

Loro: |

devono |

|

| 8. ESSERE : |

to be |

| Io: |

sono |

Noi: |

siamo |

| Tu: |

sei |

Voi: |

siete |

| Lui: |

è |

Loro: |

sono |

|

| 9. FARE : |

to make or do |

| Io: |

faccio |

Noi: |

facciamo |

| Tu: |

fai |

Voi: |

fate |

| Lui: |

fa |

Loro: |

fanno |

|

| 10. INSEGNARE : |

to teach |

| Io: |

insegno |

Noi: |

insegniamo |

| Tu: |

insegni |

Voi: |

insegnate |

| Lui: |

insegna |

Loro: |

insegnano |

|

| 11. METTERSI : |

to put on |

| Io: |

mi metto |

Noi: |

ci mettiamo |

| Tu: |

ti metti |

Voi: |

vi mettete |

| Lui: |

si mette |

Loro: |

si mettono |

|

| 12. PERDERSI : |

to get lost |

| Io: |

mi perdo |

Noi: |

ci perdiamo |

| Tu: |

ti perdi |

Voi: |

vi perdete |

| Lui: |

si perde |

Loro: |

si perdono |

|

| 13. POTERE : |

to be able |

| Io: |

posso |

Noi: |

possiamo |

| Tu: |

puoi |

Voi: |

potete |

| Lui: |

può |

Loro: |

possono |

|

| 14. PRENDERE : |

to take |

| Io: |

prendo |

Noi: |

prendiamo |

| Tu: |

prendi |

Voi: |

prendete |

| Lui: |

prende |

Loro: |

prendono |

|

| 15. PREPARARSI : |

to get ready |

| Io: |

mi preparo |

Noi: |

ci prepariamo |

| Tu: |

ti prepari |

Voi: |

vi preparate |

| Lui: |

si prepara |

Loro: |

si preparano |

|

| 16. PROIBIRE : |

to forbid |

| Io: |

proibisco |

Noi: |

proibiamo |

| Tu: |

proibisci |

Voi: |

proibite |

| Lui: |

proibisce |

Loro: |

proibiscono |

|

|

|

|

INTRODUCTIONS

|

|

Manuela: Ciao Giorgia, come stai?

Giorgia: Bene, grazie! E tu?

Manuela: Anch’ io! Oh, ciao Veronica! Che piacere vederti! Dove vai?

Veronica: Ciao Manuela! Io vado a Milano. E tu?

Manuela: Anch’ io vado a Milano.

Veronica: Lei è una tua amica?

Manuela: Sì, studiamo insieme all’università.

Veronica: Piacere, io sono Veronica! E tu come ti chiami?

Giorgia: Piacere, io mi chiamo Giorgia. Di dove sei?

Veronica: Io sono di Cagliari, e tu?

Giorgia: Io sono di Sassari ma studio a Cagliari. E tu che cosa fai?

Veronica: Anch’io sono una studentessa. Quanti anni hai?

Giorgia: 20. E tu?

Veronica: Io ho 21 anni.

Introductions in Italian

Informal

A: Giulia, ti presento il mio amico David.

B: Piacere di conoscerti!

C: Piacere mio!

A: Maria, ecco il mio nuovo vicino.

B: Piacere, io sono Maria. Tu come ti chiami?

C: Mi chiamo David, piacere!

Formal

A: Buonasera signora Riva, le presento il mio amico.

B: Sono Giovanna, molto lieta!

C: Piacere, David.

A: Scusi, è lei la dottoressa Rossi?

B: Si sono io, e lei come si chiama?

A: Sono Maria Ricci, piacere.

|

Look at the conjugation of the following verbs:

|

ESSERE (to be)

|

AVERE (to have)

|

CHIAMARSI (to call yourself)

|

|

Io sono

Tu sei

Lui/Lei è

|

Io ho

Tu hai

Lui /Lei ha

|

Io mi chiamo

Tu ti chiami

Lui/Lei si chiamaPresent Perfect (Passato Prossimo)

|

How to say hello and goodbye in Italian.

|

|

|

Ciao Hi

Buongiorno Good morning

Buonasera Good evening

Salve Hello

|

Arrivederci Goodbye

A dopo See you later

A domani See you tomorrow

A presto See you soon

|

|

ESSERE (to be)

|

AVERE (to have)

|

VOLERE (to want)

|

FARE (to make)

|

|

Io sono

Tu sei

Lui/Lei è

Noi siamo

Voi siete

Loro sono

|

Io ho

Tu hai

Lui /Lei ha

Noi abbiamo

Voi avete

Loro hanno

|

Io voglio

Tu vuoi

Lui/Lei vuole

Noi vogliamo

Voi volete

Loro vogliono

|

Io faccio

Tu fai

Lui/Lei fa

Noi facciamo

Voi fate

Loro fanno

|

Saying Hello in Italian

INCONTRO TRA AMICHE – Dialogo informale

SAYING HELLO TO FRIENDS – informal dialogue

A: Ciao Anna!

B: Ciao Francesca, come stai?

A: Molto bene grazie, e tu?

B: Non c’è male, grazie.

INCONTRO TRA ADULTI – Dialogo formale

SAYING HELLO FORMALLY

A: Buongiorno signora Rossi!

B: Buongiorno, come sta?

A: Abbastanza bene, grazie. E lei?

B: Così così.

Saying Goodbye in Italian

Informal:

A: Ciao Monica, ci vediamo dopo!

B: Ciao Tania, a più tardi!

A: Buonanotte Valentina, alla prossima volta!

B: Ciao, a presto!

Formal:

A: ArrivederLa professoressa!

B: Arrivederci ragazzi! A domani!

Saying Hello in Italian

INCONTRO TRA AMICHE – Dialogo informale

SAYING HELLO TO FRIENDS – informal dialogue

A: Ciao Anna!

B: Ciao Francesca, come stai?

A: Molto bene grazie, e tu?

B: Non c’è male, grazie.

INCONTRO TRA ADULTI – Dialogo formale

SAYING HELLO FORMALLY

A: Buongiorno signora Rossi!

B: Buongiorno, come sta?

A: Abbastanza bene, grazie. E lei?

B: Così così.

|

BERE (to drink)

|

AIUTARE (to help)

|

MANGIARE (to eat)

|

|

Io bevo

Tu bevi

Lui /Lei beve

Noi beviamo

Voi bevete

Loro bevono

|

Io aiuto

Tu aiuti

Lui /Lei aiuta

Noi aiutiamo

Voi aiutate

Loro aiutano

|

Io mangio

Tu mangi

Lui/Lei mangia

Noi mangiamo

Voi mangiate

Loro mangiano

|

4) The plural of nouns are formed in this way:

|

Masculine

|

Feminine

|

|

libro – libri

coltello – coltelli

albero – alberi

|

matita – matite

strada – strade

casa – case

|

|

AT THE STATION

|

|

Giorgia: Io vorrei qualcosa da mangiare. E voi?

Manuela e Veronica: Si, anche noi! Andiamo in quel ristorante vicino!

|

|

ORDERING FOOD AT THE RESTAURANT

|

|

Giorgia: Buongiorno, io vorrei un piatto di spaghetti, grazie.

Cameriere: Vorrebbe altro?

Giorgia:No, grazie.

Manuela: Anche io vorrei un piatto di spaghetti. con il pomodoro fresco.

Veronica: Per me una bistecca con insalata.

Cameriere: Qualcosa da bere?

Giorgia:3 bottiglie di acqua naturale, grazie!

Veronica: Scusi, potrebbe portarci il conto?

Cameriere: Voilà! In tutto 30 euro!

Giorgia:Grazie e arrivederci!

Cameriere: Arrivederci!

Present Perfect (Passato Prossimo)

The present perfect tense is used to express something that happened in the past, and which is completely finished (not habitual or continuous). To form this compound tense, which can translate as something happened, something has happened, or something did happen, conjugate avereor sometimes essere and add the past participle. To form the past participle, add these endings to the appropriate stem of the infinitives:

| -are |

-ato |

| -ere |

-uto |

| -ire |

-ito |

Verbs that can take a direct object are generally conjugated with avere. Verbs that do not take a direct object (generally verbs of movement), as well as all reflexive verbs, are conjugated with essere and their past participle must agree in gender and number with the subject. Avere uses avere as its auxiliary verb, while essere uses essere as its auxiliary verb. Negative sentences in the present perfect tense are formed by placingnon in front of the auxiliary verb. Common adverbs of time are placed between avere/essere and the past participle.

Io ho visitato Roma. I visited Rome.

Tu non hai visitato gli Stati Uniti. You didn’t visit the United States.

Abbiamo conosciuto due ragazze. We met two girls.

Maria è andata in Italia. Maria went to Italy. (Note the agreement of the past participle with the subject.)

Ho sempre avuto paura dei cani. I’ve always been afraid of dogs.

Hai già finito di studiare? Have you already finished studying?

→ In addition, some verbs take on a different meaning in the present perfect: conoscere means to meet and sapere means to find out (or to hear).

Reflexive Verbs in the Present Perfect Tense

Since all reflexive verbs use essere as the auxiliary verb, the past participle must agree with the subject. The word order is reflexive pronoun + essere + past participle.

Mi sono divertita. I had fun.

Si è sentito male. He felt bad.

Prepositions & adverbs of place

| at, to |

a |

over / above |

sopra |

| in |

in |

under / below |

sotto |

| on / up |

su |

inside |

dentro |

| from, by |

da |

outside |

fuori |

| of |

di |

around |

intorno a |

| with |

con |

between |

tra |

| without |

senza |

among |

fra |

| for |

per |

near |

vicino a |

| next to |

accanto a |

far |

lontano da |

| behind |

dietro |

before |

prima (di) |

| in front of |

davanti a |

after |

dopo (di) |

| across |

attraverso |

against |

contro |

| down |

giù |

toward |

verso |

Reflexive Verbs:

Reflexive verbs express actions performed by the subject on the subject. These verbs are conjugated like regular verbs, but a reflexive pronoun precedes the verb form. This pronoun

always agrees with the subject. In the infinitive form, reflexive verbs have -si attached to them with the final e dropped. Lavare is to wash, therefore lavarsi is to wash oneself. (Note that some verbs are reflexive in Italian, but not in English.)

Reflexive Pronouns

| mi |

ci |

| ti |

vi |

| si |

si |

Common reflexive verbs:

| to be satisfied with |

accontentarsi di |

to graduate (from college) |

laurearsi |

| to fall asleep |

addormentarsi |

to wash up |

lavarsi |

| to get up |

alzarsi |

to put on |

mettersi |

| to be bored |

annoiarsi |

to get organized |

organizzarsi |

| to get angry |

arrabbiarsi |

to make a reservation |

prenotarsi |

| to be called |

chiamarsi |

to remember to |

ricordarsi di |

| to forget to |

dimenticarsi di |

to make a mistake |

sbagliarsi |

| to graduate (from high school) |

diplomarsi |

to feel (well, bad) |

sentirsi (bene, male) |

| to have a good time |

divertirsi |

to specialize |

specializzarsi |

| to shave (the face) |

farsi la barba / radersi |

to get married |

sposarsi |

| to stop (oneself) |

fermarsi |

to wake up |

svegliarsi |

| to complain about |

lamentarsi di |

to get dressed |

vestirsi |

Io mi lavo. I wash myself.

Noi ci alziamo presto. We get up early.

Si sveglia alle sette. She wakes up at seven.

The plural reflexive pronouns (ci, vi, si) can also be used with non-reflexive verbs to indicate a reciprocal action. These verbs are called reciprocal verbs and are expressed by the words each other in English.

| to embrace |

abbracciarsi |

to run into |

incontrarsi |

| to help |

aiutarsi |

to fall in love with |

innamorarsi |

| to kiss |

baciarsi |

to greet |

salutarsi |

| to understand |

capirsi |

to write to |

scriversi |

| to meet |

conoscersi |

to phone |

telefonarsi |

| to exchange gifts |

farsi regali |

to see |

vedersi |

| to look at |

guardarsi |

|

|

Ci scriviamo ogni settimana. We write to each other every week.

Vi vedete spesso? Do you see each other often?

Basic Conversation:

| yes |

si |

|

| no |

no |

|

| please / you’re welcome |

Per piacere / prego or figurati |

|

| you’re very welcome |

Sei veramente il benvenuto |

|

| thank you |

grazie |

|

| thank you very much |

grazie mille |

|

| thanks |

grazie |

|

| Excuse me! |

Mi scusi! |

|

Communication

| English |

Italian |

Pronunciation

(Audio) |

| I understand. |

Capisco |

|

| I don’t understand |

Non capisco |

|

| Hello (on the phone) / I beg your pardon? |

Pronto |

|

| What does that mean? |

Cosa significa? |

|

| I don’t know. |

non lo so |

|

| I don’t speak Polish. |

Non parlo Polacco |

|

| I speak a little Polish. |

Parlo poco Polacco |

|

| Do you speak english? (informal) |

Parli Inglese? |

|

| Do you speak english? (formal) |

Lei parla Inglese? |

|

| Yes, I do speak english. |

Si, parlo inglese. |

|

| No, I don’t speak english. |

No, non parlo inglese |

|

Making acquaintances

| English |

Italian |

Pronunciation

(Audio) |

| Please talk more slowly! |

Parla più piano perfavore! |

|

| Nice to meet you! |

Piacere di conoscerti! |

|

| How are you? |

Come stai? |

|

| Good, thank you |

Bene, grazie |

|

| I’m well, thanks! |

Sto bene, grazie! |

|

| Not bad, thanks! |

Non male, grazie! |

|

| very bad |

molto male |

|

| What’s your name? |

Come ti chiami? |

|

| My name is […]. |

mi chiamo |

|

| What’s your first name? |

Qual’e il tuo nome? |

|

| My first name is […] |

Il mio nome è |

|

| How old are you? |

Quanti anni hai? |

|

| I’m […] years old. |

Ho … anni |

|

| What are your hobbies? |

Quali sono i tuoi hobby? |

|

| What do you like doing? |

Cosa ti piace fare? |

|

| What are you doing (at the moment)? |

Cosa stai facendo adesso? |

|

| Where do you live? |

Dove abiti? |

|

| I live in […] |

vivo a |

|

| I’m from England |

Vengo dall’Inghilterra |

|

| I’m English |

Sono Inglese |

|

|

-

Italian Grammar: “tu” and “Lei” forms

This lesson is about the informal and formal “tu” and “lei” forms in Italian grammar, and also covers useful phrases for first meetings.

In Italian you use the second person form “tu” (you) when speaking to someone you know or someone of your own age or younger, but “Lei” when being formal.

So for example, in formal situations we’d say “Che lavoro fa?” (What job does he/she do?) rather than “Che lavoro fai?” (What job do you do?).

Check out these informal / formal versions of conversations you might have on first meeting someone.

INFORMAL: Ciao, come stai? [Hello, how are you?]

FORMAL: Buongiorno come sta? [Good morning, how are you?]

REPLY: Bene grazie [Fine thank you.]

INFORMAL: Come ti chiami? [What is your name?]

FORMAL: Lei come si chiama? [What is your name?]

REPLY: Mi chiamo … [My name is …] / Sono … [I am … ]

INFORMAL: E tu? [And you?]

FORMAL: E Lei? [And you?]

REPLY: Piacere. [A pleasure!]

INFORMAL: Di dove sei? [Where are you from?]

FORMAL: Di dove è? [Where are you from?]

REPLY: Sono …, di … [I’m (nationality), from (city)]

INFORMAL: Dove vivi? [Where do you live?]

FORMAL: Dove vive? [Where do you live?]

INFORMAL: Come si scrive il tuo cognome? [How do you spell your surname?]

FORMAL: Come si scrive il suo cognome? [How do you spell your surname?]

INFORMAL: Come si pronuncia il tuo cognome? [How do you pronounce your surname?]

FORMAL: Come si pronuncia il suo cognome? [How do you pronounce your surname?]

INFORMAL: Quanti anni hai? [How old are you?]

FORMAL: Quanti anni ha? [How old are you?]

REPLY: Ho … anni [I am … years old]

INFORMAL: Qual è il tuo numero di telefono? [What is your telephone number?]

FORMAL: Qual è il suo numero di telefono? [What is your telephone number?]

INFORMAL: Qual è il tuo indirizzo? [What is your address?]

FORMAL: Qual è il suo indirizzo? [What is your address?]

INFORMAL: Che lavoro fai? [What is your job?]

FORMAL: Che lavoro fa? [What is your job?]

REPLY: Sono … [I am … ]

INFORMAL: Ciao, alla prossima volta! [Bye, see you at the next time!]

FORMAL: Arrivederla, spero di vederla presto! [Bye, see you at the next time!]

REPLY: A presto! [See you soon!]

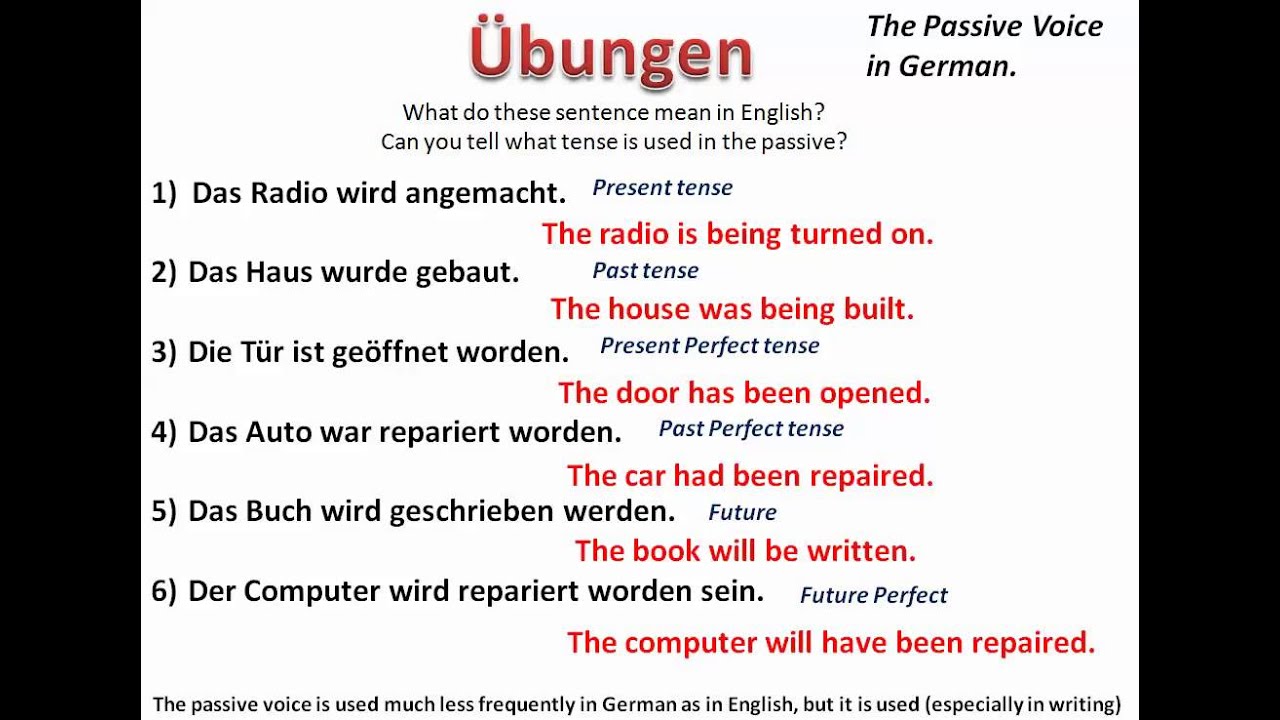

Italian Grammar Lessons: The Past / Passato Prossimo

This lesson will show you how to use the principle Italian past tense, the “passato prossimo”.

Italian has a “near past” tense and a “remote past” tense. The latter is used mostly in narratives (novels and the like) so in normal conversation you will not normally need to choose between them. Just use the passato prossimo, as explained on this page.

For English speakers, there is one point of confusion: in English, you choose between the Simple Past tense (“I studied”) and the Present Perfect tense (“I have studied”). When speaking Italian, both forms would translate as the passato prossimo, even though the passato prossimo LOOKS more like the second one (“Ho studiato” = “I have studied”??) because of the use of the auxiliary verb “avere”.

It’s confusing, but the thing to remember is that when you’re talking, you use the passato prossimo 99% of the time.

The “passato prossimo” is formed with the auxiliary verb essere OR avere + participio passato (past participle).

Just in case you’re still vague on the conjugation of “essere” and “avere”, here they are:

essere – to be

io sono

tu sei

lui/lei è

noi siamo

voi siete

loro sono

avere – to have

io ho

tu hai

lui/lei ha

noi abbiamo

voi avete

loro hanno

You probably don’t know the “participio passato” (past participle) of the verbs you’ve learnt, but not to worry!

You can normally form the “participio passato” from the infinitive of a verb (this only applies to “regular” verbs) by changing the ending of verb:

-are → ato (mangiare-mangiato)

-ere → uto (avere-avuto)

-ire → ito (dormire-dormito)

So when you want to talk about a past action or event, you need to use avere or essere plus the past participle. But which one? Avere or essere?

The majority of verbs use “avere”, just like in English (I have studied). For example:

Paola ha dormito a lungo.

Mario ha visitato un museo.

Io e Marco abbiamo pranzato in un locale tipico.

I ragazzi hanno mangiato una pizza.

But essere is used with:

– verbs of movement

– verbs of changing state

– reflexive verbs

For example:

Paola è andata al cinema.

Mario è andato al cinema.

Io e Maria siamo andate al cinema.

I ragazzi sono andati a casa.

Note that with “essere” the ending of the past participle changes to reflect the gender and singluar/plural of the subject.

The final thing you need to remember is that there are regular and irregular past participle forms.

Examples of regular past participle forms:

andare – (essere) andato/a

avere – (avere) avuto

tornare – (essere) tornato/a

dormire – (avere) dormito

cercare – (avere) cercato

montare – (avere) montato