French Articles

Articles are small words that you use only with nouns. They both present a noun and indicate the gender and number of a noun. French has

definite, indefinite, and

partitive articles. The following sections describe these three types of articles and identifies when and how you should use them in your French writing and speech.

Definite articles indicate that the noun they’re presenting is specific. In English, the definite article is

the. French has three different definite articles, which tell you that the noun is masculine, feminine, or plural. If the noun is singular, the article is

le (for masculine nouns) or

la (for feminine nouns). If the noun is plural, the article is

les no matter what gender the noun is.

If a singular noun begins with a vowel or mute

h, the definite article

le or

la contracts to

l’, as in

l’ami (the friend) and

l’homme (the man).

Indefinite articles refer to an unspecific noun. The English indefinite articles are

a and

an. French has three indefinite articles —

un (for masculine nouns),

une (for feminine nouns), and

des (for masculine or feminine plural nouns). Which one you use depends on the noun’s gender and number.

You use the indefinite article in basically the same way in French and English — to refer to an unspecific noun, as in

J’ai acheté une voiture (I bought a car) or

Je veux voir un film (I want to see a movie). Note that

un and

une can also mean one:

J’ai un frère (I have one brother).

Des is the plural indefinite article, which you use for two or more masculine and/or feminine nouns:

J’ai des idées (I have some ideas). When you make a sentence with an indefinite article negative, the article changes to

de, meaning (not) any.

- J’ai des questions. (I have some questions.)

- Je n’ai pas de questions. (I don’t have any questions.)

Partitive articles

Partitive articles are used with things that you take only part of. They don’t exist in English, so the best translation is the word

some. There are, once again, three partitive articles, depending on whether the noun is masculine (

du), feminine (

de la), or plural (

des).

You use the partitive article with food, drink, and other uncountable things that you take or use only a part of, like air and money, as well as abstract things, such as intelligence and patience. If you do eat or use all of something, and if it is countable, then you need the definite or indefinite article

You use the partitive article with food, drink, and other uncountable things that you take or use only a part of, like air and money, as well as abstract things, such as intelligence and patience. If you do eat or use all of something, and if it is countable, then you need the definite or indefinite article. Compare the following:

- Je veux du gâteau. (I want some cake — just a piece or two.)

- Je veux le gâteau. (I want the cake — the whole one.)

- Je veux un gâteau. (I want a cake — for my birthday party.)

When a singular noun begins with a vowel or mute

h, the partitive article

du or

de la contracts to

de l’, as in

de l’eau (some water) and

de l’hélium (some helium).

Partitive Articles

Use the partitive article to expresses that you want part of a whole (some or any), to ask for an indefinite quantity (something that is not being counted). Before a noun, the partitive is generally expressed by de + the definite article. Note that de + le contract to become du and de + les contract to become des, as shown in Table 1.

Note the following about the use of the partitive article:

Although the partitive

some or any may be omitted in English, it may not be omitted in French and must be repeated before each noun.

Il prend des cèrèales et du lait. (He’s having cereal and milk.)

In a negative sentence, the partitive some or any is expressed by de or d’ without the article.

Je ne mange jamais de fruits. (I never eat any fruits.)

Je n’ai pas d’amis. (I don’t have any friends.)

Before a singular adjective preceding a singular noun, the partitive is expressed with or without the article.

C’est de (du) bon gâteau. (That’s good cake.)

Before a plural adjective preceding a plural noun, the partitive is expressed by de alone.

Ce sont de bons èlèves. (They are good students.)

Certain nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by the partitive article de ( d’ before a vowel).

The following nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by de + definite article:

la plupart (most)

bien (a good many)

la majoritè (the majority)

la plus grande partie (the majority)

La plupart des gens aiment ce film. (Most people like this movie.)

The adjectives plusieurs (several) and quelques (some) modify the noun directly.

J’adore plusieurs lègumes. (I like several vegetables.)

Il achète quelques livres. (He is buying some books.)

The partitive is not used with sans (without) and ne … ni … ni (neither … nor).

Elle prendra du thè sans citron. (She’ll take tea without lemon.)

Il ne boit ni cafè ni thè. (He doesn’t drink coffee or tea.)

Subject Pronouns

A

pronoun is a word that is used to replace a noun (a person, place, thing, idea, or quality). Pronouns allow for fluidity by eliminating the need to constantly repeat the same noun in a sentence.

A

subject pronoun replaces a

subject noun(the noun performing the action of the verb).

Je

Je

Unlike the English pronoun “I,” the pronoun

je is capitalized only when it begins a sentence.

Je becomes

j’ before a vowel or vowel sound (

y and

unaspiratedh — meaning that no puff of air is emitted when producing the h sound):

- J’adore le français. (I love French.)

- Voilà où j’habite. (There’s where I live.)

Tu

Tu is used to address one friend, relative, child, or pet and is referred to as the familiar form of “you.” The

u from

tu is never dropped for purposes of elision:

Tu es mon meilleur ami. (You are my best friend.)

Vous

Vous is used in the singular to show respect to an older person or when speaking to a stranger or someone you do not know very well.

Vous is the polite or formal form of “you:”

Vous êtes un patron très respecté. (You are a very respected boss.)

In addition,

vous is always used when speaking to more than one person, regardless of the degree of familiarity.

Il and elle

Il (he) and

elle (she) may refer to a person or to a thing (it):

- L’homme arrive. (The man arrives.) Il arrive. (He arrives.)

- Le colis arrive. (The package arrives.) Il arrive. (It arrives.)

- La dame arrive. (The lady arrives.) Elle arrive. (She arrives.)

- La lettre arrive. (The letter arrives.) Elle arrive. (It arrives.)

On

On refers to an indefinite person: you, we, they, or people in general.

On is often used in place of

nous, such as in the following:

on part(we’re leaving).

Ils and elles

Ils refers to more than one male or to a combined group of males and females, despite the number of each gender present.

Elles refers only to a group of females.

- Anne et Luc partent. (Ann and Luke leave.) Ils partent. (They leave.)

- Anne et Marie partent. (Ann and Marie leave.) Elles partent. (They leave.)

Ce

The pronoun

ce (it, he, she, this, that, these, those), spelled

c’ before a vowel, is most frequently used with the verb

être (to be):

c’est (it is) or

ce sont (they are).

Ce replaces

il,

elle,

ils, and

elles as the subject of the sentence in the following constructions:

- Before a modified noun:C’est un bon avocat. (He’s a good lawyer.)

But, when unmodified, the following is correct:

Il est avocat. (He’s a lawyer.)

- Before a name:C’est Jean. (It’s John.)

- Before a pronoun:C’est moi. (It is me.)

- Before a superlative:C’est le plus grand. (It’s the biggest.)

- In dates:C’est le dix mars.(It’s March 10th.)

- Before a masculine singular adjective that refers to a previously mentioned idea or action:Il est important. (He is important.) C’est évident. (That’s obvious).

- Before an adjective + à + infinitive (the form of any verb before it is conjugated): C’est bon à savoir. (That’s good to know.)

Use

il in the following constructions:

- To express the hour of the day:Il est deux heures. (It’s 2 o’clock.)

- With an adjective + de + infinitive:Il est bon de manger. (It’s good to eat.)

- With an adjective before que: Il est important que je travaille. (It is important that I work.)

Using Object Pronouns

Object pronouns are used so that an object noun doesn’t have to be continuously repeated. This allows for a more free‐flowing conversational tone. When using object pronouns, make sure your conjugated verb agrees with the subject and not the object pronoun. Table 1 lists direct and indirect object pronouns.

The forms

me, te, se, nous, and

vous are both direct, indirect object, and reflexive pronouns.

Direct object pronouns

Direct objects (which can be nouns or pronouns) answer the question as to whom or what the subject is acting upon. It may refer to people, places, things, or ideas. A direct object pronoun replaces a direct object noun and, unlike in English, is usually placed before the conjugated verb.

- Tu regardes le film. (You watch the movie.): Tu le regardes. (You watch it.)

- Je t’aime. (I love you.)

- Tu m’aimes. (You love me.)

Indirect object pronouns

Indirect objects (which can be nouns or pronouns) answer the question of to or for whom the subject is doing something. They refer only to people. An indirect object pronoun replaces an indirect object noun, and, unlike in English, is usually placed before the conjugated verb. As a clue, look for the preposition

à (to, for), which may be in the form of

au (the contraction of

à +

le)

, à l’, à la, or

aux (the contraction of

à +

les), followed by the name or reference to a person.

- Elle écrit à Jean. (She writes to John.): Elle lui écrit. (She writes to him.)

- Tu m’offres un sac à main. (You offer me a purse.)

- Je t’offre un sac à main. (I offer you a purse.)

Verbs that take an indirect object in English do not necessarily take an indirect object in French. The following verbs take a direct object in French:

- attendre (to wait for)

- chercher (to look for)

- écouter (to listen to)

- espérer (to hope for/to)

- faire venir (to call for)

- payer (to pay)

Verbs that take a direct object in English do not necessarily take a direct object in French. The following verbs take an indirect object in French because they are followed by à:

- convenir à (to suit)

- désobéir à (to disobey)

- faire honte à (to shame)

- faire mal à (to hurt)

- faire peur à (to frighten)

- obéir à (to obey)

- plaire à (to please)

- répondre à (to answer)

- ressembler à (to resemble)

- téléphoner à (to call)

The expression

penser à (to think about) is followed by a stress pronoun; for example,

Je pense à lui/elle. (I think about him/her).

The following verbs require an indirect object because they are followed by à. Note the correct preposition to use before the infinitive of the verb.

- apprendre (teach) à quelqu’un à + infinitive

- enseigner (teach) à quelqu’un à + infinitive

- conseiller (advise) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- défendre (forbid) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- demander (ask) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- ordonner (order) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- pardonner (forgive) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- permettre (permit) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- promettre (promise) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- rappeler (remind) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

- reprocher (reproach) à quelqu’un de + infinitive

With the French verbs

plaire (to please),

falloir (to be necessary), and

manquer (to miss), the French indirect object is the subject in the English sentence:

- Ce cadeau me plaît. (I like this gift. This gift is pleasing to me.)

- Il me faut un stylo. (I need a pen. A pen is necessary for me.)

- Tu me manques. (I miss you. I am missing to you.)

The adverbial pronoun (y)

The adverbial pronoun

y (pronounced ee) means “there” when the place has already been mentioned.

Y can also mean “it,” “them,” “in it/them,” “to it/them,” or “on it/them.”

Y usually replaces the preposition

à + the noun object of the preposition, but it may also replace other prepositions of location or position, such as

chez (at the house/business of)

, dans (in)

, en (in),

sous (under), or

sur (on) + noun:

- Je vais à Paris. (I’m going to Paris.) J’y vais. (I’m going there.)

- Il répond à la note. (He answers the note.) Il y répond. (He answers it.)

- Tu restes dans ton lit. (You stay in the hotel.) Tu y restes. (You stay in it.)

Y is used to replace

de + noun only when

de is part of a prepositional phrase showing location:

L’hôtel est près de l’aéroport. (The hotel is near the airport.)

L’hôtel y est. (The hotel is there.)

Never use

y to replace à + a person. Indirect object pronouns are used for this purpose:

Je parle à Luc. (I speak to Luke.)

Je lui parle. (I speak to him.)

Sometimes

y is used in French but is not translated into English:

Il va au cinéma? (Is he going to the movies?)

Oui, il y va. (Yes, he is.)

The adverbial pronoun (en)

The pronoun

en refers to previously mentioned things or places.

Enusually replaces de + noun and may mean some or any, of it/them, about it/them, from it/them, or from there:

- Je veux de la glace. (I want some ice cream.) J’en veux. (I want some [of it]).

- Tu ne bois pas de lait. (You don’t drink any milk.) Tu n’en bois pas. (You don’t drink any.)

- Il parle de l’examen. (He speaks about the test.) Il en parle. (He speaks about it.)

- Vous sortez du café. (You leave the cafe.) Vous en sortez. (You leave [from] it.)

En is always expressed in French even though it may have no Engish equivalent or is not expressed in English:

As‐tu du temps? (Do you have any time?)

Oui, j’en ai. (Yes, I do.)

Note the following rules governing the use of

en:

- En is used with idiomatic expressions requiringde.

- J’ai besoin de film. (I need film.) J’en ai besoin. (I need some.)

- Enis used to replace a noun (de + noun) after a number or a noun or adverb of quantity.

- Je prépare six gâteaux. (I’m preparing six cakes.) J’en prépare six. (I’m preparing six [of them].)

- Tu bois une tasse de thé. (You drink a cup of tea.) Tu en bois. (You drink a cup [of it].)

- Enonly refers to people when de means some. In all other cases (when de + a noun mean “of” or “about” a person), a stress pronoun is used.

- I have a lot of sons. (J’ai beaucoup de fils.) I have a lot of them. (J’en ai beaucoup.)

The position of object pronouns

An object pronoun is placed before the verb to which its meaning is tied, usually before the conjugated verb. When a sentence contains two verbs, the object pronoun is placed before the infinitive:

- Je le demande. (I ask for it.) Je ne le demande pas. (I don’t ask for it.)

- Il va en boire. (He is going to drink some of it.) Il ne va pas en boire. (He isn’t going to drink some of it.)

In an affirmative command, an object pronoun is placed immediately after the verb and is joined to it by a hyphen. The familiar command forms of ‐

er verbs (regular and irregular — retain their final

s before

y and

en to prevent the clash of two vowel sounds together. Put a liaison (linking) between the final consonant and

y or

en:

Restes‐y!(Stay there!) But:

N’y reste pas! (Don’t stay there!)

In compound tenses, the object pronoun is placed before the conjugated helping verb:

J’ai parlé à Nancy. (I spoke to Nancy.)

Je lui ai parlé. (I spoke to her.)

Double object pronouns

The term

double object pronouns refers to using more than one pronoun in a sentence at a time, as follows:

The following examples show how double object pronouns are used before the conjugated verb, before the infinitive when there are two verbs, in the past tense, and in a negative command. Note the different order of the pronouns in the affirmative command:

- Before the conjugated verb:Elle me la donne. (She gives it to me.)

- Before the infinitive with two verbs:Vas‐tu m’en offrir? (Are you going to offer me any?)

- In the past tense:Tu le lui as écrit. (You wrote it to her.)

- In a negative command:Ne me le montrez pas. (Don’t show it to me.)

But note the difference in an affirmative command:

Montrez‐le‐moi, s’il vous plaît. (Please show it to me.)

In an affirmative command, m

oi + en and

toi + en become

m’en and

t’en respectively:

- Donne‐m’en, s’il te plaît. (Please give me some.)

- Va t’en. (Go away.)

Independent (Stress) Pronouns

Independent pronouns, listed in Table 1, may stand alone or follow a verb or a preposition. They are used to emphasize a fact and to highlight or replace nouns or pronouns.

Independent pronouns are used as follows:

To stress the subject: Moi, je suis vraiment indépendant

To stress the subject: Moi, je suis vraiment indépendant. (Me, I’m really independent.)

When the pronoun has no verb:Qui veut partir? (Who wants to leave?)

Moi. (Me.)

After prepositions to refer to a person or persons: Allons chez elle. (Let’s go to her house.)

After c’est: C’est moi qui pars. (I’m leaving.)

After the following verbs:

- avoir affaire à (to have dealings with)

- être à (to belong to)

- faire attention à (to pay attention to)

- penser à (to think about [of)])

- se fier à (to trust)

- s’intéresser à (to be interested in)

- Ceci est à moi. (This belongs to me.)

In compound subjects:

- Lui et moi allons au restaurant. (He and I are going to the restaurant.)

- Sylvie et toi dînez chez Marie. (Sylvia and you are dining at Marie’s.)

If

moi is one of the stress pronouns in a compound subject, the subject pronoun

nous is used in summary (someone + me = we) and the conjugated verb must agree with

nous. If

toi is one of the stress pronouns in a compound subject, the subject prounoun

vous is used in summary (someone + you [singular] = you [plural]) and the conjugated verb must agree with the

vous. Neither

nous nor

vous has to appear in the sentence.

With ‐ même(s) to reinforce the subject: Je suis allé au concert moi‐même. (I went to the concert by myself.)

Relative Pronouns

A

relative pronoun (“who,” “which,” or “that”) joins a main clause to a dependent clause. This pronoun introduces the dependent clause that describes someone or something mentioned in the main clause. The person or thing the pronoun refers to is called the

antecedent. A relative clause may serve as a subject, a direct object, or an object of a preposition.

Qui (subject) and que (direct object)

Qui

Qui (subject) and que (direct object)

Qui (“who,” “which,” “that”) is the subject of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a verb in the dependent clause).

Qui may refer to people, things, or places and follows the format

antecedent +

subject +

verb:

C’estla femmequia gagné. (She’s the woman who won.)

The verb of a relative clause introduced by

qui is conjugated to agree with its antecedent:

C’est moi qui choisis les bons cafés. (I am the one who chooses the good cafés.)

Que (“whom,” “which,” or “that”) is the direct object of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a noun or pronoun). Although frequently omitted in English, the relative pronoun is always expressed in French.

Que may refer to people or things and follows the format

antecedent +

direct object +

pronoun:

C’est l’homme que j’

adore. (He’s the man [that] I love.)

Qui and lequel (objects of a preposition)

Qui (meaning “whom”) is used as the object of a preposition referring to a person.

- Anne est la femme avec qui je travaille. (Anne is the woman with whom I am working.)

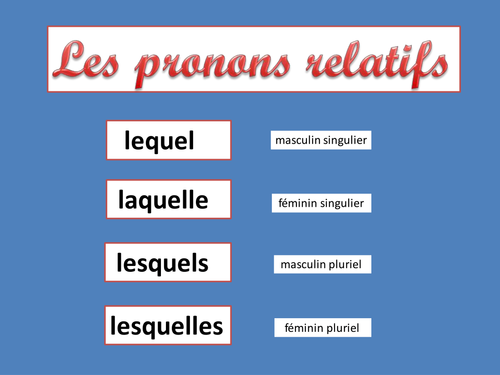

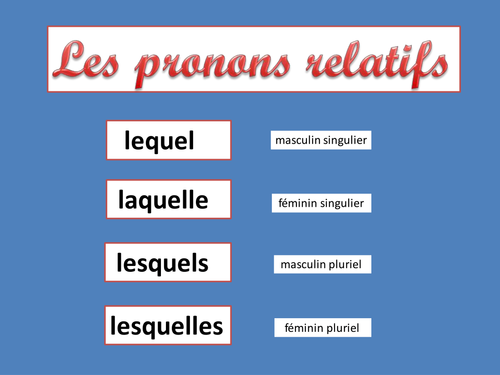

Lequel, laquelle, lesquels, lesquelles (“which” or “whom”) are used as the object of a preposition referring primarily to things. The form of

lequel must agree with the antecedent. Select the proper form of

lequel after consulting Table 1, for example,

Voilà la piscine dans laquelle je nage. (There is the pool in which I swim.)

Lequel and its forms contract with the prepositions

à and

de, as shown in Table 2:

Some examples include the following:

- Ce sont les hommes auxquels elle pense. (Those are the men she is thinking about.)

- C’est la classe de laquelle je parlais. (That’s the class I was talking about.)

Ce qui and ce que

The relative pronouns

ce qui and

ce que are used when no antecedent noun or pronoun is present:

- Ce quimeans “what” or “that which” and is the subject of a verb: Je me demande ce qui se passe. (I wonder what is happening.)

- Ce que means “what” (that which) and is the object of a verb: Tu sais ce que ça veut dire. (You know what that means.)

How to Conjugate ER Verbs in French

One thing English speakers who are learning French struggle with is learning how to conjugate all the different verbs. Most French verbs typically end in -er, -re, or -ir. The biggest group is verbs that end in -er. Verbs that fall into this group that follow the same conjugation pattern are called regular -er verbs. Once you know how to conjugate one regular -er verb, you know how to conjugate all regular -er verbs! Let’s take a look at the process.

Steps to Follow Conjugating Regular ER Verbs in the Present Tense

To conjugate any regular -er verb in the present tense, you will follow the steps outlined below.

1.) Take the infinitive form of the verb, and drop the

-er off the end of the verb to get the verb stem. (For example, take the infinitive form of the verb

parler, and remove the

-er. You are left with the verb stem

parl-.)

2.) Determine the subject pronoun you are conjugating the verb with, and add the appropriate ending from the chart below.

| Subject Pronoun |

Ending |

| Je |

-e |

| Tu |

-es |

| Il/Elle/On |

-e |

| Nous |

-ons |

| Vous |

-ez |

| Ils/Elles |

-ent |

Practice Conjugating

Let’s now practice this conjugation pattern with some common regular -er verbs in French.

| Parler (to speak) |

Donner (to give) |

Aimer (to like) |

| Je parle (pahrle) |

Je donne (done) |

J’aime* (ehm) |

| Tu parles (pahrle) |

Tu donnes (done) |

Tu aimes (ehm) |

| Il/Elle/On parle (pahrle) |

Il/Elle/On donne (done) |

Il/Elle/On aime (ehm) |

| Nous parlons (pahrl-ohn) |

Nous donnons (done-ohn) |

Nous aimons (ehm-ohn) |

| Vous parlez (pahrl-ay) |

Vous donnez (done-ay) |

Vous aimez (ehm-ay) |

| Ils/Elles parlent (pahrle) |

Ils/Elles donnent (done) |

Ils/Elles aiment (ehm) |

How to Conjugate IR Verbs in French

Verbs and Conjugation

In French, verbs have a set of endings. We call this a

conjugation. A verb like

choisir (pronounced: shwah-zeer), meaning ‘to choose,’ is called an -IR verb. To conjugate the verb, we chop off the -IR at the end of the word and put on the correct ending.

The ending for the verb corresponds to who is doing the verb. The person (or thing) doing the verb is called the

subject. In French, subjects are:

- je (pronounced: zhuh), meaning ‘I’

- tu (pronounced: tooh), meaning ‘you’ (singular, informal)

- il, elle (pronounced: eel, el), meaning ‘he’ or ‘she’

- nous (pronounced: nooh), meaning ‘we’

- vous (pronounced: vooh), meaning ‘you’ (plural, formal)

- ils, elles (pronounced: eel, el), meaning ‘they’

-IR Verb Endings

This chart shows the endings for -IR verbs in French:

| je _____ -is |

nous _____-issons |

| tu _____ -is |

vous _____-issez |

| il / elle _____ -it |

ils / elles _____-issent |

To say ‘I choose,’ we use the verb

chosir (meaning ‘to choose’) but take off the

-ir. This leaves us with

chois-. This first part of the verb, without an ending, is called the

stem. We add an ending to the stem. For

je (meaning ‘I’), the ending is

-is. So ‘I choose’ is

je choisis (pronounced: zhuh shwah-zee).

Pronunciation

The endings for

je,

tu,

il and

elle all sound like ‘ee.’

| French |

Pronunciation |

| je choisis |

zhuh shwah-zee |

| tu choisis |

tyooh shwah-zee |

| il / elle choisit |

eel / el shwah-zee |

Notice that the

il and

elle forms end with

-it, while the

je and

tu forms end with

-is. The written forms are different, but the pronunciation is exactly the same!

The plural forms–we, you (all), they–sound slightly different. The ending

-issons sounds like ‘ee-ssahn,’

-issezsounds like ‘ee-say’, and

-issent sounds like ‘eess.’

| French |

Pronunciation |

| nous choisissons |

nooh shwah-zee-ssahn |

| vous choisissez |

vooh shwah-zee-say |

| ils / elles choisissent |

eel / el shwah-zeess |

Common -IR Verbs

| French |

Pronunciation |

Meaning |

| Finir |

fee-neer |

to finish |

| Grandir |

grahn-deer |

to grow up |

| Réussir |

ray-ooh-seer |

to succeed |

| Réfléchir |

ray-flay-sheer |

to think about; to reflect |

| Maigrir |

may-greer |

to lose weight |

| Grossir |

groh-seer |

to gain weight |

Finir

Let’s take the verb

finir as an example. Imagine that Pierre wants to play video games. His mom says OK, but first ‘you finish the homework’–

tu finis les devoirs (pronounced: tooh fee-nee lay dehv-wahr).

Pierre’s a good student. He reminds his mom, ‘I always finish homework’–

je finis toujours les devoirs(pronounced: zhuh fee-nee tooh-zhor lay dehv-war). Pierre’s brother Richard pipes up, ‘We always finish homework!’–

nous finissons toujours les devoirs (pronounced: nooh fee-nee-sahn tooh-zhor lay dehv-wahr). Mom thinks, ‘That’s true, they always finish homework,’–

ils finissent toujours les devoirs (pronounced: eel fee-neess tooh-zhor lay dehv-wahr).

How to Conjugate RE Verbs in French

In French, verbs have sets of endings. This lesson introduces you to the endings for verbs that end in -RE. You will learn several -RE verbs, such as ‘vendre’ (to sell), ‘perdre’ (to lose), and ‘attendre’ (to wait.)

Subjects And Verbs

In French, verbs have different endings for each subject (like ‘I’, ‘you,’ ‘we,’ etc). Let’s review some subject pronouns:

- je (pronounced: zhuh), meaning ‘I’

- tu (pronounced: tooh), meaning ‘you’ (singular)

- il / elle (pronounced: eel / el), meaning ‘he / she’

- nous (pronounced: nooh), meaning ‘we’

- vous (pronounced: vooh), meaning ‘you’ (plural or formal)

- ils / elles (pronounced: eel / el), meaning ‘they’

Conjugation

The pattern of endings for a verb is called a

conjugation. A verb like

vendre (pronounced: vahn-druh), meaning ‘to sell,’ is called an -RE verb. To conjugate the verb, we chop off the -RE at the end of the word. This leaves us with the

stem (the beginning part of the word). We then put on the correct ending. For

vendre, the stem is

vend-.

Let’s take a look at the for -RE endings for conjugation patterns:

| Conjugation Pattern |

-RE verbs |

| je _____ -s |

nous _____ -ons |

| tu _____ -s |

vous _____ -ez |

| il, elle _____ |

ils, elles _____ -ent |

You’ll notice that the

je and

tu forms are exactly the same. They both end with

s–however, the

s is silent. The

il /

elle form is unusual, because there is no extra ending.

Pronunciation

Let’s look at the verb

rendre, which means ‘to turn in’ (for example, to turn in homework).

- je rends (pronounced: zhuh rahn), meaning ‘I turn in’

- tu rends (pronounced: tooh rahn), meaning ‘you turn in’ (singular ‘you’)

- il / elle rend (pronounced: eel / el rahn), meaning ‘he / she turns in’

- nous rendons (pronounced: nooh rahn-dahn), meaning ‘we turn in’

- vous rendez (pronounced: vooh rahn-day), meaning ‘you turn in’ (plural or formal ‘you’)

- ils / elles rendent (pronounced: eel / el rahnd), meaning ‘they turn in’

Notes About Pronunciation

Let’s look at details regarding pronunciation for these conjugation patterns:

Singular: je, tu, il, elle

The

je,

tu, and

il /

elle forms all have the exact same pronunciation. Notice that the

il /

elle form of the verb does not have an

s at the end.

Plural: nous, vous, ils, elles

Most final consonants in French are silent. For the

nous form, the ending is

-ons, with the

s being silent. For the

vous form, the

-ez ending is pronounced

ay. For the

ils /

elles form, the

-ent ending is silent.

Vendre (To Sell)

Imagine that your French friend, Sandra, needs money. She might tell you

Je vends la voiture (pronounced: zhuh vahn lah vwah-tuhr), meaning ‘I’m selling my car.’ Her kids, Pierre and Jacques, want to help by selling their toys, or

les jouets (pronounced: lay zhooh-ay). The tell you

Nous vendons les jouets.

Later, you tell you neighbor what’s going on–

elle vend la voiture (pronounced: ell vahn lah vwah-tuhr) and

ils vendent les jouets (eel vahnd lay zhooh-ay).

Notice that when Sandra says

je vends or when you say

elle vend, we don’t hear the ‘d’ sound. (The

s in

je vendsis also silent). But when we say

ils vendent or

elles vendent, we DO make a

d sound at the end of the word. The

-ent’ is silent–but because it’s there, we pronounce that d

.

Perdre (To Lose)

We saw that

rendre means ‘to turn in.’ This is what students do with homework, or

les devoirs (pronounced: lay dehv-wahr.) Unfortunately, students sometimes also lose their homework!

Perdre means ‘to lose.’ Imagine a group of friends who have different homework habits:

- Pierre: Je rends les devoirs. (pronounced: zhuh rahn lay dehv-wahr)

- Albert : Je perds les devoirs. (pronounced: zhuh pehr lay dehv-wahr)

- Pierre et Marie : Nous rendons les devoirs. (pronounced: nooh rahn-don lay dehv-wahr)

- Albert et Jacques : Nous perdons les devoirs. (pronounced: nooh pehr-don lay dehv-wahr)

Être Meaning

In almost every conversation you will need the French verb

être.

Être (pronounced: ay-tr, with a soft ‘r’ at the end) is used to indicate how things are. Literally meaning ‘to be’

être can be conjugated with the various French pronouns, paired with adjectives or used in numerous idiomatic expressions.

Conjugation

Each French pronoun requires a different conjugation of the verb

être. This table shows you a pronoun, the correct conjugation of

être, the English meaning of the conjugation, and the conjugation pronunciation.

| Subject Pronoun |

Être Conjugation |

Pronunciation |

English Meaning |

| je (I) |

suis (am) |

swee |

I am |

| tu (you) |

es (are) |

ay |

You are |

| il (he) |

est (is) |

ay |

He is |

| elle (she) |

est (is) |

ay |

She is |

| nous (we) |

sommes (are) |

sohm |

We are |

| vous (you) |

êtes(are) |

eht |

You are (formal) or You all are |

| ils (they) |

sont (are) |

sohn |

They are |

| elles (they) |

sont (are) |

sohn |

They are (feminine) |

Conjugation Examples

Imagine you are talking about the nationalities of your friends and yourself. Study the above chart and following sentences and note how the verb

être is conjugated and used with adjectives. In this case the adjective is the nationality American.

Je suis Américain. I am American.

Et toi? And you?

Tu es américain? Are you American?

Paul est Américain. Paul is American.

Nous sommes Américains. We are Americans.

Vous êtes Américains? Are you all Americans?

Ils sont Américains. They are Americans.

Julie et Diane, elles sont Américains aussi. Julie and Diane, they are Americans too.

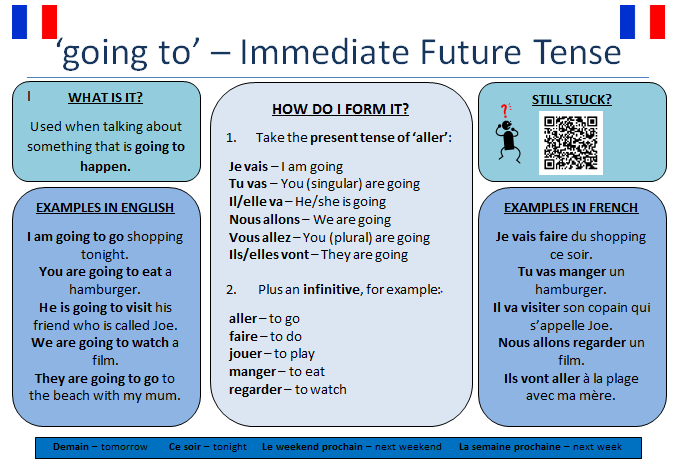

Remember,

aller is an irregular -er verb, and its conjugation in the present tense does not follow the typical conjugation pattern. In fact, you’ll notice that a lot of conjugations begin with a ‘V!’ It has irregular conjugations in some other tenses too, but you’ll learn about those later.

Present Tense Conjugation

Alright, let’s see this conjugation in chart form, and then we’ll make some sample sentences.

| Pronoun |

Verb |

| Je |

Vais (pronounced Vai) |

| Tu |

Vas (Pronounced Va) |

| Il/Elle/On |

Va (Pronounced Va) |

| Nous |

Allons (Pronounced Al-lon, but see the note below) |

| Vous |

Allez (Pronounced Al-lay, but see the note below) |

| Ils/Elles |

Vont (Pronounced vonh) |

In French, if a word ends in ‘S’ or a ‘Z’ sound, and the next word begins with a vowel, you pronounce those two words together with a Z sound in between. Since

nous and

vous end with an ‘S,’ and

allons and

allez begin with a vowel, you will need to follow this rule. As a result,

nous allons is pronounced ‘neuz-al-lon’ and

vous allez is pronounced ‘veuz al-lay.’

Also, the French present tense encompasses both the ideas of ‘You go’ and ‘You are going.’ In other languages, these are two different forms, but in French, both are represented by the present tense.

So let’s put

aller to work. Remember in French that you almost always have to have a noun or pronoun in front of a verb. Here are some sample sentences with

aller.

- Je vais a la banque. – I go to the bank.

- Tu vas. – You are going. (This is not a command, but a statement)

- Elle va a une école. – She goes to a school.

- Nous allons avec Marie. – We go with Marie.

- Vous allez. – You are going. (Again, not a command, but a statement)

Avoir in French: Conjugation & Meaning

While the verb may just mean ‘to have,’

avoir has many uses beyond that. In fact, without

avoir, entire tenses of the French language would be impossible! In this lesson, we’re not only going to look at the forms of

avoir in both present and perfect tenses, but we’re also going to look at examples of it in action. Finally, we’ll also learn more about just how useful

avoir is throughout the French language.

Conjugation

First of all, let’s conjugate

avoir in the present tense:

| Pronoun and Verb |

Pronunciation |

| J’ai |

J’ay |

| Tu as |

tu ah |

| Il a |

Il ah |

| Nous avons |

Newz-ah-vohn |

| Vous avez |

Vewz-ah-vey |

| Ils ont |

Ilz-onh |

Now before we go any further, do you see how each of those pronunciations took into account the pronoun? This is an important part of French and makes sure that you sound educated. A lot of the time, you’ll use

avoirwith a pronoun. However, sometimes you won’t. Therefore, here’s a pronunciation chart that separates those last three versions out:

| Pronoun |

Verb |

Pronunciation |

| Nous |

Avons |

Ah-vohn |

| Vous |

Avez |

Ah-vey |

| Ils |

Ont |

Onh |

That way, you can say

Marie et moi avons without having to sound harsh by saying

Marie et moi, nous avons. Both mean ‘Marie and I have’, but the first one is much more casual, and frankly not as forceful as the second one. The first example is just normal conversation, while the second one is very much the style you’d expect a mother to use when saying to go clean a room now.

French Verb Voir Conjugation

A Few Facts About the Verb Voir

Voir is an Irregular Verb.

In French, there are three groups of verbs. The verbs of the first and second groups are regular, which means they follow a pattern–a regular verb usually keeps the same radical followed by the conjugated endings. Once you know how to conjugate one verb of either of those groups, you can easily conjugate all of the other verbs belonging to that group.

The verbs of the third group are

irregular, which basically means that there’s no strict pattern that can help you figure out how they’re conjugated. They often have multiple radicals. They run wild and free! So you just need to learn them individually.

Voir (pronounced vwahr) is one of these irregular verbs, and it means ‘to see.’

Voir is a Transitive Verb

This means that, just like the verb ‘to see’ in English, it can be followed by a direct object.

- Example: Je vois mon cousin aujourd’hui. (I am seeing my cousin today.)

Now… let’s see if we can tame those wild conjugations.

Voir in the Present Tense

In the present tense,

voir has two radicals:

voi- and

voy-.

| je |

vois |

(zhuh-vwah) |

| tu |

vois |

(tü-vwah) |

| il/elle/on |

voi |

(eel/ehl/on-vwah) |

| nous |

voyons |

(noo-vwah-yon) |

| vous |

voyez |

(voo-vwah-yay) |

| ils/elles |

voient |

(eel/ehl-vwah) |

- Example: Du haut de la tour Eiffel, nous voyons tout Paris. (From the top of the Eiffel Tower, we see all of Paris)

Voir in the Imparfait

The

imparfait, or imperfect, tense is simpler:

Voir only has one radical,

voy-, which is followed by the regular

imparfait endings.

| je |

voyais |

(zhuh-vwah-yay) |

| tu |

voyais |

(tü-vwah-yay) |

| il/elle/on |

voyait |

(eel/ehl/on-vwah-yay) |

| nous |

voyions |

(noo-vwah-yeeon) |

| vous |

voyiez |

(voo-vwah-yay) |

| ils/elles |

voyaient |

(eel/ehl-vwah-yay) |

- Example: Quand nous étions petits, nous voyions notre grand-mère tous les dimanches. (When we were little, we saw our grandmother every Sunday.)

Note the distinction between the first-person plural in the present tense,

nous voyons, and the first-person plural in the imperfect,

nous voyions, Despite the different spellings, the pronunciation is basically the same (just a tiny bit more emphasis on the ee sound in the

imparfait).

Voir in the Passé Composé

In the

passé composé,

voir is conjugated with the auxiliary

avoir followed by the past participle

vu.

| j’ |

ai vu |

(zheh-vü) |

| tu |

as vu |

(tü-ah-vü) |

| il/elle/on |

a vu |

(eel/ehl/on-ah-vü) |

| nous |

avons vu |

(noo-ah-von-vü) |

| vous |

avez vu |

(voo-ah-vay-vü) |

| ils/elles |

ont vu |

(eel/ehl-on-vü) |

- Example: Hier, Sophie et Claire ont vu un tigre au zoo. (Yesterday, Sophie and Claire saw a tiger at the zoo.)

Voir in the Future Simple

In the future simple,

voir takes on a completely different radical:

ver-, which is followed by the regular future simple endings. This radical will come back later in the conditional.

| je |

verrai |

(zhuh-vay-reh) |

| tu |

verras |

(tü-vay-rah) |

| il/elle/on |

verra |

(eel/ehl/on-vay-rah) |

| nous |

verrons |

(noo-vay-ron) |

| vous |

verrez |

(voo-vay-ray) |

| ils/elles |

verront |

(eel/ehl-vay-ron) |

- Example: Vous verrez vos amis demain soir. (You will see your friends tomorrow.)

Faire in French: Conjugation & Meaning

Why is faire an important verb?

The verb

faire (pronounced like the English word

fair but with the French /r/ sound) is a great verb to have in your back pocket because it’s definitely a multi-tasker. Some interesting facts about this verb are:

1) most weather expressions in French use

faire, for example to talk about what the weather is doing

2) many individual sports and activities use this verb, for example to express that you do a certain sport

3) used in math equations to mean

equals in English

4) used in causative constructions where you have had something done to a person or thing, for example having your dog groomed

5) Numbers 1 and 2 on this list are the most important usages for beginners. It’s also used in many, many other expressions in French. Trust us, this is a high-frequency verb!

How to use it in sentences: the conjugations

The verb

faire is considered to be an irregular verb, meaning that the conjugations used in order to create a subject-verb agreement do not follow typical patterns. So, break out the flash cards and commit this one to memory. The following examples of conjugations express how to use the verb to talk about activities and sports.

Singular Forms:

Je

fais (fay) du sport = I do sports

Fais-tu du yoga? = Do you do yoga?

Il/Elle

fait (fay) du ski nautique = He/She does/goes skiing

Plural Forms:

Nous

faisons (fuh zahn) de la danse = We do dance

Faites(fet)-vous du camping? = Do you do/go camping?

Ils/Elles

font (fohn) une promenade = They go for a walk

Remember, many individual sports – ones that don’t require a team to play – as well as activities take this verb, and it can also translate into English as

go instead of make or do.

Savoir Conjugation

Knowing how to say you know something or telling a friend, ‘I don’t know’ is pretty important in conversation, even French conversations. But to do that, first you have to learn how to conjugate the verb

savior(pronounced: sah-vwahr),

to know.

| Subject Pronoun |

Savoir Conjugation |

Pronunciation |

English Meaning |

| je (I) |

sais |

(say) |

I know |

| tu (you) |

sais |

(say) |

you know (singular) |

| il/elle (he/she) |

sait |

(say) |

he/she knows |

| nous (we) |

savons |

(sah-vahn) |

we know |

| vous (you) |

savez |

(sah-vay) |

you know (plural) |

| ils/elles (they) |

savent |

(sahv) |

they know |

Now that we’ve got that down, let’s look at the different ways that savior is used in conversations.

To Know How

To express that someone knows how to do something, we use a form of the verb

savoir plus a second verb. Let’s look at some examples using

savoir plus the verb

nager (pronounced: nah-zhay)

to swim:

Imagine that your French friend, Ariane, has come to visit. You want to go swimming, so you ask her,

‘Tu sais nager?’ meaning, ‘Do you know how to swim?’. She would answer

‘Je sais nager’ meaning ‘I know how to swim.’ Then, your friends Frank and Elizabeth arrive. You ask them

‘Vous savez nager?’ meaning ‘Do you (guys) know how to swim?’ They answer,

‘Nous savons nager’ meaning ‘We know how to swim.’

Notice how the sentences use different forms of the verb

savoir, but the word

nager never changes.

Let’s look at some more examples:

- Je sais conduire (pronounced: zhuh say kon-dweer), meaning ‘I know how to drive.’

- Elle sait conduire (pronounced: el say kon-dweer), meaning ‘She knows how to drive.’

- Il sait danser (pronounced: eel say dahn-say), meaning ‘He knows how to dance.’

- Ils savent danser (pronounced: eel sahv dahn-say), meaning ‘They know how to dance.’

Vouloir Conjugation

Vouloir: To Want

Imagine that you get to spend a few weeks visiting France. What do you want to do? What do you want to eat? To express what you want, say

je veux (pronounced: zhuh veuh), which means ‘I want.’ Whether you stay in a hotel or with French hosts, you’ll have plenty of opportunities to discuss what you want. For example, you might say:

je veux visiter le Louvre (pronounced: zhuh veuh vee-see-tay luh loov-ruh). Perhaps your main goal is to learn French. You can explain that:

je veux apprendre le français (pronounced: zhuh veuh ah-prahn-druh luh frahn-say).

Conjugating Vouloir

In English, we say ‘I want’ and ‘he wants.’ The verb is ‘want,’ but its form changes slightly depending on who is speaking. In French, verbs have different endings. Putting the right endings on a verb is called

conjugating the verb. Notice the endings for the verb

vouloir:

| VOULOIR |

(pronounced: vooh-lwahr) to want |

| je veux (zhuh veuh) |

nous voulons (nooh vooh-lahn) |

| I want |

we want |

| tu veux (tyooh veuh) |

vous voulez (vooh vooh-lay) |

| you want (singular) |

you want (plural) |

| il / elle veut (eel / el veuh) |

ils / elles veulent (eel / el vuhl) |

| he / she wants |

they want |

Pronunciation Hints

Notice that the verb endings for

je, tu, il and

elle are all pronounced the same. The verb ending is the same for the

je and

tu forms. For

il / elle , the ending changes. When you’re speaking, you can’t hear a difference.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the

je, tu, il / elle, and

ils / elles forms all start with

veu. This letter blend sounds like ‘euh.’ To pronounce it correctly, think about making the sound down in your throat, at the spot where you swallow.

On the other hand,

vouloir as well as

voulons and

voulez all begin with the sound

vou. This letter blend rhymes with ‘ooh’ — as in

Ooh là là! This sound is formed with your lips. Pucker up like you’re going to give someone a big kiss to make the

ooh sound for French words like

vouloir, voulons, voulez as well as

vous and

nous.

Examples With Vouloir

Imagine that two friends, Paul and Robert, are traveling together in France. As they discuss traveling from Paris to the city of Avignon, they might debate whether to

prendre le train (pronounced: prahn-druh luh trahn) or

louer une voiture (pronounced: looh-ay oohn vwah-tyuhr). Paul might ask Robert:

Tu veux louer une voiture? Robert might reply,

Non, je veux prendre le train.

Paul and Robert are staying with their friend Nathalie in Paris. They tell her about their plan:

Nous voulons prendre le train. Nathalie might ask them, ‘Do you want to leave tomorrow?’ She would say

Voulez-vous partir demain? (pronounced: vooh-lay vooh pahr-teer duh-mahn).

Feminine Adjectives in French

Let’s get personal. Do you have a girlfriend? How would you describe her to someone? Is she pretty? Is she short or tall? Or we could talk about your grandmother. Would you say she is funny? Is she strong or frail? In French, since these people are feminine, when you describe them, the adjectives must also be feminine!

Did you know that in French,

objects can also be feminine? For example, in French, cars are feminine! The word for car,

la voiture, is a feminine word! So, now how would you describe your car? Is it fancy? Expensive? What color is it? All of these adjectives must be feminine when you are describing your car.

Examples of Adjectives

Add an ‘e’ at the end of most adjectives to create the feminine form. Some examples of masculine and feminine forms are:

- grand—grande (tall) – pronounced (grahn) and (grahnduh) with nasal ‘n’ sound

- joli—jolie (pretty) – pronounced (zhoh-lee)

- bleu—bleue (blue) – pronounced (bluh)

- fort —forte (strong) – pronounced (fohr) and (fohrtuh)

- marrant—marrante (funny) pronounced (marrahn) and (marrahn-tuh) with nasal ‘n’ sound

- fâché —fâchée (angry) pronounced (fah-shay)

When pronouncing these, we do not say the last consonant in the masculine form. When the feminine ‘e’ is added, we hear the last consonant. For example:

fort is pronounced like (for), but

forte is pronounced similar to (fort) in English.

Some adjectives have a slight change in the last consonant before adding the feminine ‘e.’ For example, some adjectives ending in

f go from

f to

ve.

- sportif—sportive (athletic) Pronounced- (sporteef) and (sporteev)

- créatif—créative (creative) Pronounced- (cray-ah-teef) and (cray-ah-teev)

Pronounce the’ ‘f or the ‘v’ as it is written.

Some adjectives double the last consonant before adding the feminine ‘e.’ For example:

- mignon—mignonne (cute) – pronounced (meenyohn) with nasal ‘n,’ and (meenyunn)

- bon—bonne (good) – pronounced (boh-n) with nasal ‘n,’ and (bun)

- gentil—gentille (kind) – pronounced (zhahn-tee) and (zhahn-teeyuh) with nasal ‘n’

The double consonants are pronounced in the feminine form, but usually the single consonants in the masculine form are pronounced nasally or not at all. For instance, pronounce ‘bon’ like the word (bone) but with a nasal ‘n’ sound and ‘bonne’ similar to (buhnn).

Describing Your Car in French

Let’s try some sentences to describe your car!

- Ma voiture est bleue. (My car is blue.) Pronounced- (mah vwa-teeoor ay bluh)

- Elle est petite. (It is small.) Pronounced- (el ay puhteetuh).

How about your grandmother? Let’s try describing her:

-

(My grandmother is funny, but my grandfather is also funny.)Ma grand-mère est marrante, mais mon grand-père est aussi marrant.

Pronounced-(mah gran-mayr ay marrantuh may mohn granpayr ay oh-see marran)

Notice that the grandfather has the masculine adjective form, and the grandmother has the feminine form of the adjective.

Working with Possessive Adjectives

In this lesson we’re going to learn how to use possessive adjectives in French. While it may first seem like there are a lot of them (15 compared to 7 in English), the good news is that they all work together in a big system. It’s important to learn these, and chances are that your teacher will want you to memorize them.

Before we get started, there are a few quick rules to keep in mind:

- Possessive adjectives agree in number and gender with the words they modify.

- Since these adjectives are based on the speaker to determine their use, you don’t have to modify them to reflect the speaker.

- If a feminine word is being modified and starts with a vowel, use the masculine version of the adjective.

- Possessive adjectives always come before the word they modify.

First Person Pronouns

Let’s dig right in with the first person. Remember that the first person singular form, what we would call ‘I’, is ‘je’ (pronounced Juh) while the first person is ‘nous’ (pronounced Nu). Here are our possessive adjectives:

| Pronoun |

Masc. |

Fem. |

Plural |

| Je |

Mon (Pronounced Moh) |

Ma (Pronounced Ma) |

Mes (Pronounced Meh) |

| Nous |

Notre (Pronounced Not-rah) |

Notre |

Nos (Pronounced Noh) |

Now let’s practice with those. If you are trying to say ‘my bag,’ you’d say

mon sac, since ‘sac’ (pronounced sac) is a masculine singular work. Meanwhile, if you are talking about more than one bag that you happened to have ownership of, then it would be

mes sacs.

Let’s say that you actually shared those bags with your friends. In that case, if it were just the one bag you’d say

notre sac, while if you had more than one, it would be

nos sacs.

What if it wasn’t a sac? What if it was a suitcase, or

une valise (pronounced va-leez)? What would you say then? Again, if it were yours, you’d say

ma valise. If it were plural, it would change to ‘mes valises.’ If you and your friends owned the suitcases, the possessive adjective wouldn’t change.

Second Person Pronouns

Now let’s talk about someone else’s suitcases and bags. Let’s pretend that you were talking to me about my stuff. That would mean that you’d have to use the second person, or the ‘tu’ or ‘vous’ forms. Let’s start by looking at a table with the forms:

| Pronoun |

Masc. |

Fem. |

Plural |

| Tu |

Ton (pronounced Toh) |

Ta (Pronounced Ta) |

Tes (Pronounced Teh) |

| Vous |

Votre (pronounced vot-rah) |

Votre |

Vos (pronounced Voh) |

Let’s try some of them. If you were to say ‘your bag’ to me, you’d say

ton sac. Likewise, if you were commenting on multiple bags, you’d say

tes sacs. However, if it was my suitcase you were referring to, it would be

ta valise.

What if you were addressing more than one person, or you were trying to show me a lot of respect? In that case, you’d use ‘votre’ adjectives. So you’d say

votre sac or

vos sacs. Also, just like ‘notre,’ there’s only one singular form, so even if it was my suitcase, you’d still say ‘votre valise.’

The Regular French Adjective

When you speak French, you’ll need adjectives to add rich color to your speech. Would you prefer to taste a dessert, or would you prefer to taste a delicious, heavenly, luscious, mouthwatering, rich, dreamy, scrumptious dessert? Most people would choose the latter, even if they knew nothing else about the dessert being served. It’s all because of the words describing the dessert. These are adjectives, or simply put, describing words.

Here are a few simple French adjectives.

grand (tall)

petit (short, little)

joli (pretty)

laid (ugly)

Adjectives and Gender

Let’s see if you can find a pattern at work.

Imagine you meet two new friends when you visit Paris. You meet Lucas and his girlfriend, Anissa. Why don’t we use some adjectives we know to describe them?

Lucas est grand. Il n’est pas petit. Il est joli. Il n’est pas laid.

Anissa n’est pas grande. Elle est petite. Elle est jolie. Elle n’est pas laide.

Do you see a difference between the way the adjectives are spelled when we describe Lucas and when we describe Anissa?

It’s an extra e! We have to match up the adjective with the gender of the subject. When we are talking about Lucas, we don’t add an e. This is called the masculine or base form of the adjective. When we are talking about Anissa, we add the e. This is called the feminine form.

Nouns in French Have Genders!

Every object or thing in French has a gender, either masculine or feminine. You can memorize the gender when you learn a new word, or you can look it up in a reliable French dictionary. This can help when you need to decide whether or not to add that extra e when you’re using an adjective.

Let’s try it out. Here’s a new noun.

The word for fox, un renard, is masculine. Does it require an extra e if you use an adjective? Let’s test your guess.

Le renard est intelligent. (The Fox is smart.)

If you guessed no, then you were right! Because un renard is masculine, there is no extra e on the end of the base form of the adjective.

Let’s try another new noun.

The word for a turtle, une tortue, is feminine. Do you think it will require an extra e if you use an adjective?

La tortue est lente. (The turtle is slow.)

Because une tortue is feminine, then we must add on an extra e at the end of the adjective.

What if there is already an ‘e’ in the base form of the adjective?

You’ll find that there are quite a few French adjectives that have an e already in their basic, masculine form.

It’s very important to look closely at the kind of e that ends the adjective.

If it’s an accented e, then you must add an extra e in the feminine form.

This is true with fatigué (tired) and désolé (sorry).

You might say, ‘Il est fatigué; elle est fatiguée.’ (He is tired; she is tired.) As you can see in this example, we added an e in the feminine form, right after that accented e.

Now, on the other hand, if you find an adjective that ends with just an e without an accent, then you do nothave to add another e in the feminine form: It’s already done for you.

This is true with faible (weak) and jeune (young), for instance.

You might say, ‘Il est jeune et elle est jeune.’ (He is young and she is young.) Notice we didn’t have to add an eto the feminine form in this example. It was already there!

Here are some more regular adjectives you can work with and add to your growing vocabulary.

fort (strong)

faible (weak)

amusant (funny)

intéressant (interesting)

méchant (mean)

sympathique (nice)

mauvais (bad)

fatigué (tired)

désolé (sorry)

lent (slow)

rapide (quick)

sale (dirty)

propre (clean)

riche (rich)

pauvre (poor)

facile (easy)

difficile (difficult)

triste (sad)

content (happy)

jeune (young)

agréable (agreeable, okay)

désagréable (disagreeable, unpleasant)

Match it Up! Adjectives and Number

Just as French adjectives must be masculine or feminine according to the objects they describe, they also have to accurately match up to the number of objects they are describing.

Don’t despair! This is easy to do.

Let’s start with a good example.

Here’s another new noun.

We have here a group, or plural, with a masculine noun, designating the sheep.

Let’s apply an adjective and see what it looks like. Let’s say that they are happy: They do look happy grazing together like that.

Les moutons sont contents.

Interrogative Adjectives: Grammar Basics

Interrogative adjectives in French can be masculine (

quel,

quels) or feminine (

quelle,

quelles). Like all other adjectives, they must agree in number and gender with the nouns they modify.

Here is a quick reference chart:

| Masculine |

Feminine |

| quel (singular) |

quelle (singular) |

| quels (plural) |

quelles (plural) |

Whether you’re using interrogative adjectives to modify a masculine or feminine noun, plural or singular,

quel/quelle/quels/quelles is always pronounced ‘kell.’

Interrogative adjectives are often used in sentences where English would use the word ‘what,’ e.g. ‘What books do you like?,’ or

Quels livres aimes-tu? (kell leevrö ehm-tü). In this example,

livres is the noun. It’s plural and masculine, so we use the interrogative adjective

quels.

Here are a couple more examples:

Tu aimes quels films? and

Quel est ton groupe préféré? In the first example,

films is a plural masculine noun, which corresponds with

quels, while the noun in the second example,

groupe, is singular and masculine, so it takes

quel.

Interrogative adjectives almost always come directly before the noun they are modifying, and they are typically used in the beginning of a sentence before the subject and verb (

Quels livres aimes-tu?). But interrogative adjectives need not always come at the beginning of a sentence. They might come after the subject and verb (

Tu aimes quels films?).

Also, there is an exception to interrogative adjectives coming directly before the noun they modify: a sentence construction using the verb être, which follows the general format: interrogative adjective + conjugated form of être + noun (

Quel est ton groupe préféré?).

Note that

lequel and

laquelle, while often used in similar contexts, are interrogative pronouns, and are thus not covered in this lesson. Furthermore, although French exclamatory adjectives are identical to interrogative adjectives, they are used not to ask questions, but to express emotion, as in

Quel bonheur! (What happiness!)

Asking What and Which

Interrogative adjectives be useful both in professional contexts, and in making small talk. In a meeting, for instance, you might be asked

Quelles sont vos idées? (What are your ideas?) If comparing notes with friends, you might ask

Quels livres faut-il acheter pour ton cours de français? (What books do you have to buy for your French course?)

Here are some further examples of how you might use interrogative adjectives:

- Quelle écharpe penses-tu acheter? / What scarf are you thinking of buying?

- Quelles villes françaises pensez vous à visiter? / What French cities are you thinking of visiting?

- Vous préferez quelle cuisine? / What sort of cuisine do you prefer?

- Quel jardin est le plus beau? / What garden is the most beautiful?

- Quelle heure est-il? / What time is it?

French Adjectives: Placement & Examples

Describing People and Things

Sam and Liz are Americans living abroad in Angers, France, and they really want to be able to talk to their neighbors, describe their new neighbors, and talk about what goes on around them without being confusing. There are certain things Sam and Liz will need to remember about words that describe a noun or pronoun, or

adjectives, to reach their goal. This includes understanding which adjectives do and don’t conform to normal placement principles.

Normal Placement

The normal or most common placement of adjectives in a French sentence is right behind the word it describes. For example:

J’ai un vélo ‘bleu.‘ (I have a blue bike).

Elles aiment la langue ‘anglaise.‘ (They like the English language.)

Nous sommes vos voisins ‘américains.‘ (We are your American neighbors.)

C’est un homme ‘sympa.‘ (He’s a nice man.)

Nous avons des voisins ‘sincères.‘ (We have sincere neighbors.)

This order is quite different from English as you can see in the translations, and Sam and Liz are going to have to make an extra effort to get this right if they want their French-speaking neighbors to understand them.

BANGS Adjectives

B – BeautyBANGS is an acronym that Sam and Liz can use to remember which adjectives don’t follow the rules. These are describing words that normally come before the noun (there are always exceptions). It stands for:

A – Age

N – Number

G – Goodness

S – Size

Examples of adjectives that fall in each category are as follows:

| Beauty |

beau/belle/beaux/belles |

joli/jolie/jolis/jolies |

| Age |

jeune/jeunes |

viel/vieux/vieille/vieilles |

| Number |

un/deux/trois/quatre/cinq |

|

| Goodness |

bon/bonne/bons/bonnes |

mauvais/mauvaise/mauvaises |

| Size |

grand/grande/grands/grandes |

petit/petite/petits/petites |

Knowing this information, Sam and Liz are able to tell and ask their new neighbor, Monsieur LeClerc, lots of important things:

Sam:

Vous avez une ‘belle’ voiture! (You have a nice car!)

Liz:

Est-ce que c’est un ‘bon’ restaurant au coin? (Is the restaurant on the corner good?)

M LeClerc:

C’est un ‘petit’ restaurant, mais il est bon. (It’s a small restaurant, but it is good.)

Sam:

Nous avons ‘deux’ chiens. Et vous, vous avez des animaux? (We have two dogs, and do you have any animals?)

Special Adjectives

There are also some special adjectives that don’t follow the normal positioning or BANGS. Sam and Liz have to be really careful with this group of adjectives because this group can be used before or after the nouns they describe, but the meaning changes depending on where they are placed.

Here are a few of these used to help out Sam and Liz in their new neighborhood:

1.

ancien (old/former)

- Before a noun: C’est mon ancien voisin. (This is my former neighbor.)

- After a noun: C’est mon voisin ancien. (This is my ancient neighbor.)

2.

cher (dear/expensive)

- Before a noun: Cher Sam, je t’aime. (Dear Sam, I love you.)

- After a noun: Cette voiture est chère. (This car is expensive.)

French Adjectives

French Adjectives

French Conjugation

French Conjugation

Je

Unlike the English pronoun “I,” the pronoun je is capitalized only when it begins a sentence. Je becomes j’ before a vowel or vowel sound ( y and unaspiratedh — meaning that no puff of air is emitted when producing the h sound):

Je

Unlike the English pronoun “I,” the pronoun je is capitalized only when it begins a sentence. Je becomes j’ before a vowel or vowel sound ( y and unaspiratedh — meaning that no puff of air is emitted when producing the h sound):

Il and elle

Il (he) and elle (she) may refer to a person or to a thing (it):

Il and elle

Il (he) and elle (she) may refer to a person or to a thing (it):

The forms me, te, se, nous, and vous are both direct, indirect object, and reflexive pronouns.

The forms me, te, se, nous, and vous are both direct, indirect object, and reflexive pronouns.

The following verbs require an indirect object because they are followed by à. Note the correct preposition to use before the infinitive of the verb.

The following verbs require an indirect object because they are followed by à. Note the correct preposition to use before the infinitive of the verb.

To stress the subject: Moi, je suis vraiment indépendant. (Me, I’m really independent.)

When the pronoun has no verb:Qui veut partir? (Who wants to leave?) Moi. (Me.)

After prepositions to refer to a person or persons: Allons chez elle. (Let’s go to her house.)

After c’est: C’est moi qui pars. (I’m leaving.)

After the following verbs:

To stress the subject: Moi, je suis vraiment indépendant. (Me, I’m really independent.)

When the pronoun has no verb:Qui veut partir? (Who wants to leave?) Moi. (Me.)

After prepositions to refer to a person or persons: Allons chez elle. (Let’s go to her house.)

After c’est: C’est moi qui pars. (I’m leaving.)

After the following verbs:

Qui (subject) and que (direct object)

Qui (“who,” “which,” “that”) is the subject of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a verb in the dependent clause). Qui may refer to people, things, or places and follows the format antecedent + subject + verb: C’estla femmequia gagné. (She’s the woman who won.)

The verb of a relative clause introduced by qui is conjugated to agree with its antecedent: C’est moi qui choisis les bons cafés. (I am the one who chooses the good cafés.)

Que (“whom,” “which,” or “that”) is the direct object of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a noun or pronoun). Although frequently omitted in English, the relative pronoun is always expressed in French. Que may refer to people or things and follows the format antecedent + direct object + pronoun: C’est l’homme que j’ adore. (He’s the man [that] I love.)

Qui and lequel (objects of a preposition)

Qui (meaning “whom”) is used as the object of a preposition referring to a person.

Qui (subject) and que (direct object)

Qui (“who,” “which,” “that”) is the subject of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a verb in the dependent clause). Qui may refer to people, things, or places and follows the format antecedent + subject + verb: C’estla femmequia gagné. (She’s the woman who won.)

The verb of a relative clause introduced by qui is conjugated to agree with its antecedent: C’est moi qui choisis les bons cafés. (I am the one who chooses the good cafés.)

Que (“whom,” “which,” or “that”) is the direct object of a relative clause (which means that it will be followed by a noun or pronoun). Although frequently omitted in English, the relative pronoun is always expressed in French. Que may refer to people or things and follows the format antecedent + direct object + pronoun: C’est l’homme que j’ adore. (He’s the man [that] I love.)

Qui and lequel (objects of a preposition)

Qui (meaning “whom”) is used as the object of a preposition referring to a person.

Lequel and its forms contract with the prepositions à and de, as shown in Table 2:

Some examples include the following:

Lequel and its forms contract with the prepositions à and de, as shown in Table 2:

Some examples include the following:

You use the partitive article with food, drink, and other uncountable things that you take or use only a part of, like air and money, as well as abstract things, such as intelligence and patience. If you do eat or use all of something, and if it is countable, then you need the definite or indefinite article. Compare the following:

You use the partitive article with food, drink, and other uncountable things that you take or use only a part of, like air and money, as well as abstract things, such as intelligence and patience. If you do eat or use all of something, and if it is countable, then you need the definite or indefinite article. Compare the following:

Note the following about the use of the partitive article:

Although the partitive some or any may be omitted in English, it may not be omitted in French and must be repeated before each noun.

Il prend des cèrèales et du lait. (He’s having cereal and milk.)

In a negative sentence, the partitive some or any is expressed by de or d’ without the article.

Je ne mange jamais de fruits. (I never eat any fruits.)

Je n’ai pas d’amis. (I don’t have any friends.)

Before a singular adjective preceding a singular noun, the partitive is expressed with or without the article.

C’est de (du) bon gâteau. (That’s good cake.)

Before a plural adjective preceding a plural noun, the partitive is expressed by de alone.

Ce sont de bons èlèves. (They are good students.)

Certain nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by the partitive article de ( d’ before a vowel).

The following nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by de + definite article:

la plupart (most)

bien (a good many)

la majoritè (the majority)

la plus grande partie (the majority)

La plupart des gens aiment ce film. (Most people like this movie.)

The adjectives plusieurs (several) and quelques (some) modify the noun directly.

J’adore plusieurs lègumes. (I like several vegetables.)

Il achète quelques livres. (He is buying some books.)

The partitive is not used with sans (without) and ne … ni … ni (neither … nor).

Elle prendra du thè sans citron. (She’ll take tea without lemon.)

Il ne boit ni cafè ni thè. (He doesn’t drink coffee or tea.)

Note the following about the use of the partitive article:

Although the partitive some or any may be omitted in English, it may not be omitted in French and must be repeated before each noun.

Il prend des cèrèales et du lait. (He’s having cereal and milk.)

In a negative sentence, the partitive some or any is expressed by de or d’ without the article.

Je ne mange jamais de fruits. (I never eat any fruits.)

Je n’ai pas d’amis. (I don’t have any friends.)

Before a singular adjective preceding a singular noun, the partitive is expressed with or without the article.

C’est de (du) bon gâteau. (That’s good cake.)

Before a plural adjective preceding a plural noun, the partitive is expressed by de alone.

Ce sont de bons èlèves. (They are good students.)

Certain nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by the partitive article de ( d’ before a vowel).

The following nouns and adverbs of quantity are followed by de + definite article:

la plupart (most)

bien (a good many)

la majoritè (the majority)

la plus grande partie (the majority)

La plupart des gens aiment ce film. (Most people like this movie.)

The adjectives plusieurs (several) and quelques (some) modify the noun directly.

J’adore plusieurs lègumes. (I like several vegetables.)

Il achète quelques livres. (He is buying some books.)

The partitive is not used with sans (without) and ne … ni … ni (neither … nor).

Elle prendra du thè sans citron. (She’ll take tea without lemon.)

Il ne boit ni cafè ni thè. (He doesn’t drink coffee or tea.)

Conjugating Reflexive Verbs

A reflexive verb infinitive is identified by its reflexive pronoun se, which is placed before the infinitive and that serves as a direct or indirect object pronoun. A reflexive verb shows that the subject is performing the action upon itself and, therefore, the subject and the reflexive pronoun refer to the same person or thing, as in je m’appelle (I call myself), which is translated to “My name is.”

Conjugating Reflexive Verbs

A reflexive verb infinitive is identified by its reflexive pronoun se, which is placed before the infinitive and that serves as a direct or indirect object pronoun. A reflexive verb shows that the subject is performing the action upon itself and, therefore, the subject and the reflexive pronoun refer to the same person or thing, as in je m’appelle (I call myself), which is translated to “My name is.”

Some verbs must always be reflexive, whereas other verbs may be made reflexive by adding the correct object pronoun. The meaning of some verbs varies depending upon whether or not the verb is used reflexively.

Reflexive verbs are always conjugated with the reflexive pronoun that agrees with the subject: me (myself), te (yourself), se (himself, herself, itself, themselves), nous (ourselves), and vous (yourself, yourselves). These pronouns generally precede the verb. Follow the rules for conjugating regular verbs, verbs with spelling changes, and irregular verbs, depending on of the tense, as shown in Table 1:

Reflexive constructions have the following translations:

Some verbs must always be reflexive, whereas other verbs may be made reflexive by adding the correct object pronoun. The meaning of some verbs varies depending upon whether or not the verb is used reflexively.

Reflexive verbs are always conjugated with the reflexive pronoun that agrees with the subject: me (myself), te (yourself), se (himself, herself, itself, themselves), nous (ourselves), and vous (yourself, yourselves). These pronouns generally precede the verb. Follow the rules for conjugating regular verbs, verbs with spelling changes, and irregular verbs, depending on of the tense, as shown in Table 1:

Reflexive constructions have the following translations:

Consider the following most commonly used reflexive verbs. Those marked with asterisks have shoe verb spelling change within the infinitive.

Consider the following most commonly used reflexive verbs. Those marked with asterisks have shoe verb spelling change within the infinitive.

er (cut oneself)

er (cut oneself)

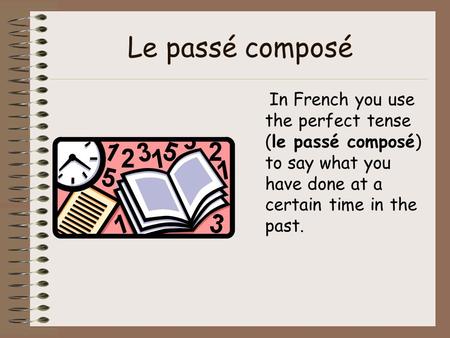

Here are some examples of the passé composé.

Elle a expliqué son problème. (She explained her problem.)

Ils ont réussi. (They succeeded.)

J’ai entendu les nouvelles. (I heard the news.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with avoir

In a negative sentence in the passé composé, ne precedes the helping verb, and the negative word (pas, rien, jamais, and so on follows it:

Je n’ai rien préparé. (I didn’t prepare anything.)

Nous n’avons pas fini le travail. (We didn’t finish the work.)

Il n’a jamais répondu à la lettre. (He never answered the letter.)

Questions in the passé composé with avoir

To form a question in the passé composé using inversion, invert the conjugated helping verb with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. Then place the negative around the hyphenated helping verb and subject pronoun:

As‐tu mangé? (Did you eat?)

N’as‐tu rien mangé? (Didn’t you eat anything?)

A‐t‐il attendu les autres? (Did he wait for the others?)

N’a‐t‐il pas attendu? (Didn’t he wait for the others?)

Here are some examples of the passé composé.

Elle a expliqué son problème. (She explained her problem.)

Ils ont réussi. (They succeeded.)

J’ai entendu les nouvelles. (I heard the news.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with avoir

In a negative sentence in the passé composé, ne precedes the helping verb, and the negative word (pas, rien, jamais, and so on follows it:

Je n’ai rien préparé. (I didn’t prepare anything.)

Nous n’avons pas fini le travail. (We didn’t finish the work.)

Il n’a jamais répondu à la lettre. (He never answered the letter.)

Questions in the passé composé with avoir

To form a question in the passé composé using inversion, invert the conjugated helping verb with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. Then place the negative around the hyphenated helping verb and subject pronoun:

As‐tu mangé? (Did you eat?)

N’as‐tu rien mangé? (Didn’t you eat anything?)

A‐t‐il attendu les autres? (Did he wait for the others?)

N’a‐t‐il pas attendu? (Didn’t he wait for the others?)

Dr. and Mrs. Vandertrampp live in the house in Figure , as illustrated in Table 1. Their name may help you memorize the 17 verbs using être. An asterisk (*) in Table 6 denotes an irregular past participle.