| Coordinate

conjunctions |

Subordinate

conjunctions |

Compound

conjunctions |

| aber

beziehungsweise

denn

oder

sondern

und |

als

bevor

bis

dass

damit

nachdem |

ob

obwohl

seit

seitdem

sobald

sofern

soweit |

sowie

während

weil

wenn

wie

wo |

weder .. noch

anstatt..zu

entweder…oder

sowohl … als (auch)

sowohl … wie (auch)

je … desto

zwar … abe |

Coordinate Conjunctions (Koordinierende Konjunktionen)

The coordinate conjunctions do not modify the position of the verb in the clause. The most common ones are:

| Coordinate

conjunction |

Meaning |

| aber |

but |

| beziehungsweise |

better put

respectively |

| denn |

because

then |

| oder |

or |

| sondern |

but

but rather |

| und |

and |

aber

It means “but”.

Die Hose ist schön, aber zu klein

The pants are pretty but too small

Er ist klug, aber faul

He’s smart but lazy

Das Angebot ist super, aber wir haben keine Zeit

The offer is great but we don’t have time

beziehungsweise

It means “better put” or “respectively” and is abbreviated often as bzw.

Ein Auto habe ich beziehungsweise meine Frau hat eins

I have a car or, better put, my wife has one.

Die Disko ist heute billiger für Frauen und Männer. Es kostet 7 Euro bzw. 10 Euro.

The disco is cheaper today for women and men. It costs 7 and 10 Euros, respectively

denn

It means then/because, etc.

Ich weinte, denn ich hatte kein Geld

I cried because I didn’t have money

Synonymns: weil

oder

Means “or”

Ich weiß nicht, ob ich lachen oder weinen soll

I don’t know whether I should laugh or cry

Wer fängt an, du oder ich?

Who starts, you or me?

sondern

Means “but” or “but rather”

Das Haus ist nicht alt, sondern neu

The house is not old but new

und

It means “and”

Meine Freunde und ich wollen ins Kino gehen

My friends and I want to go to the cinema

Subordinate Conjunctions

Subordinate conjunctions help to form subordinate clauses. One of the most interesting things about German is that the verb is placed in the last position of the clause in subordinate clauses (Main article: Sentence structure in German)

| Subordinate

conjunction |

Meaning |

| als |

when |

| bevor |

before |

| bis |

until |

| dass |

that |

| damit |

so that |

| nachdem |

after |

| ob |

whether

if |

| obwohl |

although |

| seitdem |

since |

| sobald |

as soon as |

| sofern |

provided that

as long as |

| soweit |

insofar as |

| sowie |

as soon as |

| während |

while |

| weil |

because |

| wenn |

if |

| wie |

how |

| wo |

where |

als

It means “when” if it is a subordinate conjunction. Careful: It’s used only in the past and when the past event only took place one time (temporal conjunction)

Als ich Kind war, wohnte ich in München

When I was a child, I lived in Munich

“Als” is also used for the construction of the comparative of superiority:

Er ist stärker als ich

He is stronger than me

bevor

It means “before” (temporal conjunction to show previous action or event)

Woran denkst du, bevor du einschläfst?

What do you think about before you fall asleep?

bis

It means “until” (temporal conjunction to show subsequent action or event) “Bis” can act as a subordinate conjunction:

Warte, bis du gesund bist

Wait until you are healthy

or as a preposition:

Bis in den Tod

until death

dass

It can be translated into English as “that” and is used to start a new subordinate clause.

Ich denke, dass die deutsche Sprache kompliziert ist

I think that the German language is complicated

dass vs das

Sometimes English speakers confuse “das” (relative pronoun) and “dass” (conjunction). The reason for this is because we use “that” for both words.

“das” is used to make relative clauses, which are used to give more information about a noun.

Das ist das Buch, das ich gerade lese

This is the book that I am reading

dass is to make common subordinate clauses where more information is given with a verb (Example: the verb to say)

Ich habe dir gesagt, dass er heute kommt

I told you that he’s coming today

damit

It means

“so that” (conjunction of purpose)

Ich spare, damit meine Familie einen Mercedes kaufen kann

I am saving money so that my family can buy a Mercedes

nachdem

It means “after” (temporal conjunction)

Nachdem wir aufgestanden waren, haben wir gepackt

After we got up, we packed our bags

ob

It means “whether/if” in the context of indirect questions or to show doubt.

Er hat dich gefragt, ob du ins Kino gehen möchtest

He asked you if you wanted to go to the cinema

Common mistakes: Confusing the use of ob and wenn

obwohl

It means “although” or “even though” (concessive conjunction)

Ich mag Kinder, obwohl ich keine habe

I like kids even though I don’t have any

seit

It means “since” (temporal conjunction). Seit can act as a subordinate conjunction:

Ich wohne in Köln, seit ich geboren bin

I’ve been living in Cologne since I was born

or as a preposition (seit + Dative):

Er wohnt jetzt seit 2 Jahren in diesem Haus

He’s been living in this house for two years

seitdem

It means “since” (temporal conjunction)

Ich habe keine Heizung, seitdem ich in Spanien wohne

I haven’t had heating since I’ve been living in Spain

sobald

It means “as soon as” (temporal conjunction)

Ich informiere dich, sobald ich kann

I’ll inform you as soon as I can

sofern

It means “as long as” (temporal conjunction)

Wir versuchen zu helfen, sofern es möglich ist

We will try to help as long as it’s possible

soviel

It means

“as much as” or

“for all”

Soviel ich weiß, ist sie in Berlin geboren

For all I know, she was born in Berlin

soweit

It means “as far as”

Soweit ich mich erinnern kann, war er Pilot

As far as I remember, he was a pilot

sowie

It means “as soon as”

Ich schicke dir das Dokument, sowie es fertig ist

I’ll send you the document as soon as it’s finished

während

It means “while” or “during” (temporal). While can act as a subordinate conjunction:

Während ich studierte, lernte ich auch Deutsch

While I was studying, I was also learning German

or as a preposition (während + Genitive):

Während meiner Jugendzeit war ich in Basel

During my youth I was in Basel

weil

It means

“because” (causal conjunction)

Sie arbeitet heute nicht, weil sie krank ist

She doesn’t work today because she’s sick

Synonyms: denn

wenn

It means “if” but only in certain cases. For example: “If you want to go with us, you can.” Expressing doubt would require “ob”. For example: ” I don’t know if you’d like to come with us.” It also means “whenever” (conditional conjunction)

Wenn du möchtest, kannst du Deutsch lernen

If you want, you can learn German (context of “if” or “in case”)

Wenn ich singe, fühle ich mich viel besser

If I sing, I feel much better (context of “whenever I sing…”)

Common mistakes: Confusing the use of “wenn” and “ob”.

wie

It means

“how” (modal conjunction):

Ich weiß nicht, wie ich es auf Deutsch sagen kann

I don’t know how to say it in German

or for expressions of equality:

Peter ist so dünn wie Tomas

Peter is as thin as Tomas

wo

It means “where” (local conjunction)

Ich weiß nicht, wo er Deutsch gelernt hat

I don’t know where he learned German

Compound Conjunctions

Compound conjunctions are formed by 2 words:

| Compound

conjunction |

Meaning |

| anstatt … zu |

instead of

[subordinate] |

| entweder … oder |

either… or

[coordinate] |

| weder noch |

neither… nor

[coordinate] |

| weder noch |

as well as

[subordinate] |

| sowohl … als (auch) |

as well as

[subordinate] |

| sowohl … wie (auch) |

as well as

[subordinate] |

anstatt…zu

It means “instead of”

Ich würde 2 Wochen am Strand liegen, anstatt zu arbeiten

I would be lying on the beach for 2 weeks instead of working

entweder…oder

It means “either… or”

Entweder bist du Teil der Lösung, oder du bist Teil des Problems

Either you’re part of the solution or you’re part of the problem

Die Hose ist entweder schwarz oder rot

The pants are either black or red

weder…noch

It means “neither… nor”

Weder du noch ich haben eine Lösung

Neither you nor I have a solution

sowohl … als (auch)

It means “as well as”

Ich habe sowohl schon einen Mercedes als auch einen Audi gehabt

I have had a Mercedes as well as an Audi

sowohl … wie (auch)

It means “as well as”

Ich habe sowohl ein Auto wie auch ein Motorrad

I have a car as well as a motorcycle

|

|

|

|

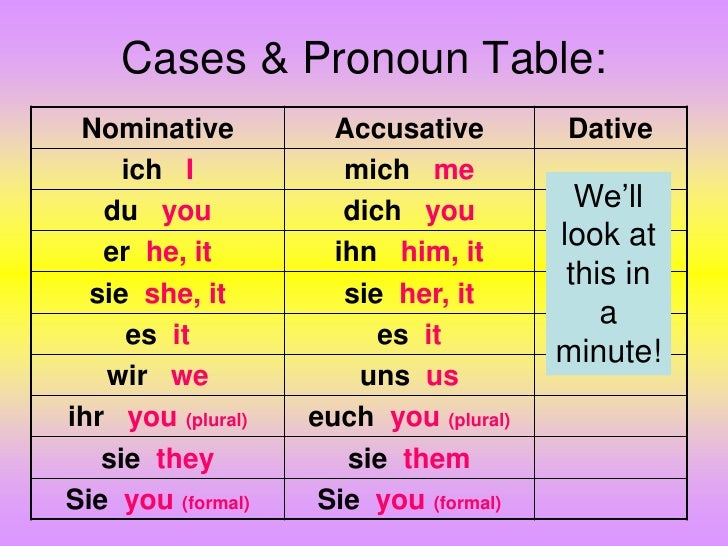

Conjunctions vs Prepositions

A conjunction is a “little word” that connects two clauses: “You’re so fine, and you’re mine”; “Long stemmed roses are the way to your heart, but he needs to start with your head.” In German, a conjunction either “cooordinates” two “equally important” clauses, or it “subordinates” one clause to the other. Subordinating conjunctions make the verb go to the end in the clause they introduce, while coordinating conjunctions leave the verb position unchanged (==> the verb will usually, but not always, be in position 2 after a coordinating conjunction). Since conjunctions determine the relation between clauses (and, because, although, as if…), it’s crucial for you to be familiar with their meanings.

A preposition is a “little word” that brings a noun or pronoun into the sentence: “Zephyr in the sky atnight I wonder, do my tears of mourning sink beneath the sun?” Prepositions don’t affect word order in German, but they do determine the case of the noun or pronoun they bring into the sentence. Since prepositions determine what the nouns or pronouns they bring into the sentence are doing there (on, under, with, without, instead of…), it’s again crucial for you to be familiar with their meanings. Click here for more information on prepositions.

A few words (e.g. seit, während) can be both conjunctions and prepositions, and you have to determine their function by looking to see if they are connecting two phrases (Ich esse SPAM, seit ich in Amerika bin: conjunction; Ich esse seit drei Stunden SPAM: preposition). English uses “after” and “before” as both conjunctions and prepositions, but German distinguishes the conjunctions nachdem and bevor from the prepositions nach and vor.

Even after reading this explanation, you’re likely to sometimes confuse prepositions and conjunctions. ==> When your instructor uses either term and you’re not sure what s/he means, please ask. Many of your classmates will be grateful to you!

|

Summary Tables

|

Please refer to the Word Order

page for practice exercises and

diagnostic exercises on this topic |

|

Usage Notes and Examples:

|

Coordinating Conjunctions

- Und, denn, sondern, aber, oder

- Other coordinating conjunctions: allein, doch, jedoch, beziehungsweise

|

Two-Part Coordinating Conjunctions |

| Subordinating Conjunctions |

|

|

Coordinating Conjunctions

These ocupy position 0 and leave the verb position the same as in the preceding clause.

| und |

and |

| denn |

because |

| sondern |

but (rather) |

| aber |

but |

| oder |

or |

| beziehungsweise |

or, or more precisely |

| allein [rare] |

but (unfortunately) |

| doch |

but, however |

| jedoch |

but, however |

|

|

Subordinating Conjunctions

These send the conjugated verb to the end of the clause.

| bevor |

before |

| ehe |

before |

| nachdem |

after |

| während |

during, while, whereas |

| seit, seitdem |

since (for time, not for “because”) |

| bis |

until, by |

| als |

when (past events) |

| wenn |

when (pres. & fut.), whenever, if |

| wann |

when (questions only) |

| obwohl |

although [can also use obgleich [less common] and obschon [least common]] |

| als ob, als wenn, als |

as if |

| solange |

as long as |

| sooft |

as often as (whenever) |

| sobald |

as soon as |

| da |

because |

| weil |

because |

| indem |

by …-ing |

| wenn |

if, when |

| ob |

whether, if [use only if you could say “whether” in English] |

| falls |

in case, if |

| um…zu |

in order to |

| damit |

so that |

| so dass |

so that |

| dass |

that |

|

|

Two-Part Coordinating Conjunctions

These ocupy position 1 (except for the “oder” in “entweder…oder”) and leave the verb position the same as in the preceding clause.

| entweder…oder |

either…or |

| weder…noch |

neither…nor |

| sowohl…als auch |

both…and |

| einerseits…andererseits |

on one hand…on the other hand |

| bald…bald |

sometimes…sometimes |

| mal…mal |

sometimes…sometimes |

| teils…teils |

partly…partly |

|

|

Usage Notes and Examples

Coordinating Conjunctions

Und, denn, sondern, aber, oder

1. Silly note for disco fans: these can be sung to the tune of “Stayin’ Alive.” Amaze your friends at Retro Nights…:

| und |

denn |

son- |

dern |

aber-oder |

aber-oder |

| ah |

ha |

ha |

ha |

stayin’alive |

stayin’alive |

2. After a coordinating conjunction, continue with the same word order as in the previous clause. The conjunction occupies “position zero.” This usually means that the conjugated verb will be in position two (or first position, if the subject is omitted–1st & 3rd example):

| Einstein war ein sauberer Mensch, aber [er] kämmte sich nie die Haare. |

Einstein was a clean person, but he never combed his hair. |

| “X-Rays” heißen auf deutsch “Röntgenstrahlen”, denn sie

wurden 1895 von Wilhelm Röntgen entdeckt. |

“X-rays” are called “Röntgen rays” in German because they were discovered by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895. |

| Das Universum wird ewig expandieren, oder [es] wird eines Tages kollabieren. |

The universe will expand eternally, or it will collapse one day. |

If, however, the previous clause has dependent word order (conjugated verb at the end), then the sentence continues with dependent word order after the coordinating conjunction:

| Es regnet, weil die Luft feucht istund es kalt ist. |

It’s raining because the air is moist and (because) it’s cold. |

| Der Autor glaubt, dass Evolution kein deterministischer Vorgang ist, sondern ein Zufall war. |

The author believes that evolution is not a deterministic process, but rather, that it was a chance occurrence. |

This applies also when coordinating and subordinating conjunctions appear side by side:

| Es regnet, weil die Luft feucht ist und weil es kalt ist. |

It’s raining because the air is moist and because it’s cold. |

| Wir sind jetzt müde, aber sobaldwir in die Deutschklasse kommen, werden wir wach [=awake]. |

We’re tired now, but as soon as we get into the German class we become awak |

Othr notes and examples

1. Aber vs sondern:

a. Use sondern if you could say “but rather” [in the sense of instead] in English.

b. Sondern must be preceded by a negation; aber can be.

c. Nicht nur is always followed by sondern auch.

| Die Sonne ist nicht sehr groß,

aber sie ist heiß. |

The sun is not very big, but it is hot. |

| Die Sonne ist nicht sehr groß,

sondern durchschnittlich. |

The sun is not very big, but rather [instead], it is average. |

| Unsere Sonne ist nicht nur groß, sondern auch heiß. |

The sun is not only big, but also hot. |

2. Denn vs weil: both give a reason, and their meanings are as similar as those of “because” and “since” in English. The only differences are that they require different word order (since weil is a subordinating conjunction), and that denn-clauses cannot start a sentence. The following sentences are all equivalent, but the last one is illegal:

| Die Dinosaurier sind ausgestorben, weil ein gewaltiger [=huge] Meteorit auf die Erde gefallen ist. |

The dinosaurs died out because a huge meteorite hit the Earth. |

| Die Dinosaurier sind ausgestorben, denn ein gewaltiger [=huge] Meteorit ist auf die Erde gefallen. |

| Weil ein gewaltiger [=huge] Meteorit auf die Erde gefallen ist, sind die Dinosaurier ausgestorben. |

Because a huge meteorite hit the Earth, the dinosaurs died out. |

| Denn ein gewaltiger [=huge] Meteorit ist auf die Erde gefallen, sind die Dinosaurier ausgestorben. |

3. Aber can follow the verb and nouns/pronouns, or just the subject. This adds emphasis. See jedoch below for more examples.

| Ein roter Riese endet oft als Neutronenstern, kann aber auch ein schwarzes Loch werden. |

A red giant often ends as a neutron star, but can also become a black hole. |

| Der Präsident ist ein Alien, wir wollen ihn aber wieder wählen. |

The president is an alien, but (still) we will vote for him again |

| Der Präsident ist ein Alien, wir wollen aber ihn wieder wählen. |

The president is an alien, but (still) we will vote for him again] |

| Der Präsident ist ein Alien, wir aber wollen wieder für ihn wählen. |

The president is an alien; we, however, will vote for him agai |

Other coordinating conjunctions: allein, doch, jedoch, beziehungsweise

allein: Can be used instead of aber to express unwelcome or unexpected problems or restrictions. Sounds formal and a little archaic.

| Es gibt viele kosmologische Theorien, allein wir wissen über 90% der Materie des Universums gar nichts. |

There are many cosmological theories, but (unfortunately) we know nothing at all about 90% of the material of the universe. |

doch, jedoch: Slightly more formal and slightly more emphatic than aber. They may occupy position 0, like und, denn, etc., or they may occupy first position, as in the second example below.

| Wir hatten Hunger, jedoch/doch ich aß das Eis nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat the ice cream. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, jedoch/dochaß ich das Eis nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat the ice cream. |

Jedoch is a little stronger than doch, and can come after the subject and/or the verb and nouns/pronouns, like aber, for added emphasis. Notice how the emphasis changes as jedoch moves around in the following sentences:

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich aß das Eis

jedoch nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat the ice cream. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich aß es jedoch nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat it. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich aß jedochdas Eis nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat the ice cream. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich aß jedoch es nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat it. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich jedoch aß das Eis nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat the ice cream. |

| Wir hatten Hunger, ich jedoch aß es nicht. |

We were hungry, but I did not eat it. |

beziehungsweise (abbrev.: bzw): This is a relatively formal synonym for oder, used with mutually exclusive alternatives. It can also mean “or more precisely.”

| Ein Hamburger kostet € 2.40, bzw. € 2.80 mit Käse. |

A Hamburger costs € 2.40, or €2.80 with cheese. |

| Die beiden gingen ins Gefängnis [=prison], beziehungsweise zum elektrischen Stuhl. |

The two of them went to prison and the electric chair respectively. |

| Homer Simpson hat den Fisch gegessen, beziehungsweise gefressen. |

Homer Simpson ate the fish, or more precisely he devoured it. |

| Die Erde kreist um die Sonne,

bzw. Sonne und Erde kreisen umeinander. |

The Earth revolves around the Sun, or more precisely the Sun and the Earth revolve around each other |

Two-Part Coordinating Conjunctions

entweder…oder: either…or

| Entweder du gibst mir € 100, oder ich gehe zur Polizei. |

Either you give me € 100 or I’m going to the police. |

| Entweder gibst du mir € 100, oderich gehe zur Polizei. |

| Du gibst mir entweder € 100, oder ich gehe zur Polizei. |

| Du kannst entweder das rote oderdas grüne Hemd tragen. |

You can wear either the red or the green shirt. |

weder…noch: neither…nor

| Du kannst weder das rote nochdas grüne Hemd tragen. |

You can wear neither the red shirt nor the green shirt. |

| Der Stern von Bethlehem war weder eine Supernova, noch (war er) ein Komet. [usual word order] |

The start of Bethlehem was neither a supernova nor a comet. |

| Weder war der Stern von Bethlehem eine Supernova, noch (war er) ein Komet. [uncommon word order] |

sowohl…als auch: both…and

| Du kannst sowohl das rote als auch das grüne Hemd tragen. |

You can wear both the red shirt and the green shirt. |

| Wir haben sowohl die Hausaufgabe gemacht, als auch alle Vokabeln gelernt. |

We did the homework and we learned the vocabulary. |

einerseits…andererseits: on the one hand…on the other hand

| Einerseits mache ich Diät, andererseits will ich gern ein Eis essen. |

On the one hand I’m on a diet, on the other hand I’d like to eat some ice cream. |

| Ich mache einerseits Diät, andererseits will ich gern ein Eis essen. |

bald…bald/mal…mal: sometimes…sometimes

| Bald regnet es, bald scheint die Sonne. |

Sometimes it rains, sometimes the sun shines. |

| Mal ist der Pandabär aggressiv, mal ist er unglaublich süß. |

Sometimes the panda bear is aggressive, sometimes it’s unbelievably sweet. |

teils…teils: partly…partly

| Wasser besteht teils aus Sauerstoff, teils aus Wasserstoff. |

Water consists partly of Oxygen, partly of Hydrogen. |

| Die Studenten gehen teils zur Bibliothek, teils bleiben sie zu Hause. |

Some of the students go to the library, some stay at home. |

| Teils gehen die Studenten zur Bibliothek, teils bleiben sie zu Hause. |

Subordinating Conjunctions ==> Verb in final position

als/wenn/wann: when. To refer to a completed event in the past, use als, even if that event went on for a long time (Als ich jung war,…; Als ich fünf war,…). Use wenn with the past tense only if you are referring to a repeated event.

In present and future tense, use wenn for when.

Use wann only for questions and indirect questions (i.e. a statement without a question mark that directly or indirectly implies uncertainty about when the event will take place).

| Als ich jung war, mochte ich Aal. |

When I was young, I liked [eating] eel. |

| Als ich 5 war, aß ich oft Aal. |

When I was 5, I often ate eel. |

| Als ich nach Ulm ging, aß ich Aal. |

When I went to Ulm, I ate eel. [this happened once] |

| Wenn ich nach Ulm ging, aß ich Aal. |

When(ever) I went to Ulm, I ate eel. [this happened repeatedly] |

| Wenn ich nach Ulm gehe, esse ich Aal. |

When I go to Ulm, I’ll eat eel [This can also mean: When(ever) I go to Ulm, I eat eel.] |

| Wann gehst du nach Ulm? |

When are you going to Ulm? |

| Ich weiß nicht, wann ich nach Ulm gehe. |

I don’t know when I’m going to Ulm [indirect question: the statement directly implies uncertainty about when I’m going]. |

| Es ist egal, wann ich nach Ulm gehe. |

It doesn’t matter when I’m going to Ulm [indirect question: the statement indirectly implies uncertainty about when I’m going]. |

Note that, although wenn can sometimes be translated as whenever, as in the fourth and fifth examples above, the best translation for whenever is immer wenn.

ob/wenn: Both translate if, but only one is right in any given sentence. If you can say whether in English, you must use ob in German. If you cannot, you must use wenn.

| Ich weiß nicht, ob das stimmt. |

I don’t know whether (if) that is right. |

| Wenn es stimmt, bin ich froh. |

If (whether) it is right, I’m happy. |

falls: in case, if. Falls can sometimes be used instead of wenn to express possibility. It is a little more tentative than wenn.

| Falls ihr es baut, werden sie kommen. |

If you build it, they will come. [more tentative] |

| Wenn ihr es baut, werden sie kommen. |

If you build it, they will come. [less tentative] |

| Nimm einen Schirm mit, falls es regnet. |

Take an umbrella along in case it rains. |

| Nimm einen Schirm mit, wenn es regnet. |

Take an umbrella along if it rains. |

bevor/ehe: before. Ehe is slightly more formal. Reminder: use bevor with actions, but vor withnouns (Wir sehen uns bevor der Film beginnt; Wir sehen uns vor dem Film).

nachdem: after. Reminder: use nachdem with actions, but nach with nouns (Wir sehen uns nachdemder Film beginnt; Wir sehen uns nach dem Film).

seitdem, seit: since. Reminders:

1. Use seitdem or seit with actions, but only seit with nouns (Wir schlafen seit/seitdem die Klasse begann; Wir schlafen seit der Klasse).2. Seitdem and seit mean “since” in the temporal sense only. They cannot be used in the sense of “because.” For this, you would have to use weil, da, or denn.

damit/so dass/um…zu: so that. See “Superwörter I” for more explanations!

da/weil: because. Da is slightly more formal.

als ob/als wenn/als: as if. Als ob is the most common of the three. Since they describe conjectures or contrary to fact conditions, these are usually used with Subjunctive II. Note: when als is used in this sense, the conjugated verb is in position 2, not in final position.

| Dieser Schmetterling sieht aus, als ob/als wenn er ein Blatt wäre. |

This butterfly looks as if it were a leaf. |

| Dieser Schmetterling sieht aus, alswäre er ein Blatt. |

Zurück nach obenbis: until; by.Bis usually means until, but can also mean by the time or by.

| Wir kitzelten Rumpelstilzchen, bis sie lächelte. |

We tickled Rumpelstizchen until she smiled. |

| Bis sie lächelte, waren viele Jahre vergangen. |

By the time she smiled, many years had passed. |

dass: that.Like its English equivalent “that,” daß can often be omitted, but in that case the verb goes to position 2.

| Einstein glaubte, daß Gott nicht würfelt. |

Einstein believed that God does not play dice. |

| Einstein glaubte, Gott würfelt nicht. |

Einstein believed [that] God does not play dice. |

indem: by …-ing. Explains how something is achieved.

| Manchmal begehen Lemminge Massenselbstmord, indem sie ins Meer springen. |

Sometimes lemmings commit mass suicide by jumping into the sea. |

| Indem er dem Lehrer eine Banane gab, sicherte sich der Student eine gute Note. |

By giving the teacher a banana, the student secured a good grade. |

obwohl/obgleich/obschon: although. Obwohl is the most common of the three, obschon is least common.

| Obgleich/obschon/obwohl es ein nützliches Wort ist, benutzen die Studenten “obwohl” selten. |

Although it is a useful word, the students rarely use “obwohl.” |

Zurück nach obensobald/solange/sooft: as soon as/as long as/as often as (whenever). These indicate the conditions under which something will happen.

| Sobald die Kinder Barney sehen, hört ihr Gehirn auf zu funktionieren. |

As soon as the children see Barney, their brain stops functioning. |

| Solange das Innere der Erde heiß ist, werden die Kontinente sich bewegen. |

As long as the interior of the earth is hot, the continents will move. |

| Der Schneider wird Daumen abschneiden, sooft ein Kind seinen Daumen lutscht. |

The tailor will cut off thumbs as often as/whenever a child sucks its thumb. |

Während: during, while. Like while in English, während can be used temporally to indicate that two actions are going on simultaneously, or “conceptually” to contrast two ideas or events. See also Superwörter II for some more details about während.

| Nero spielte seine Flöte währendRom brannte. |

Nero played his flute while Rome burned. |

| Die meisten Autos haben einen Viertakt-Motor, während der Trabant einen Zweitakt-Motor hat, wie ein Motorrad oder eine Kettensäge. |

Most cars have a four-stroke engine, while/whereas the Trabant has a two-stroke engine, like a motorcycle or a chainsaw. |

|

|

|

]]>

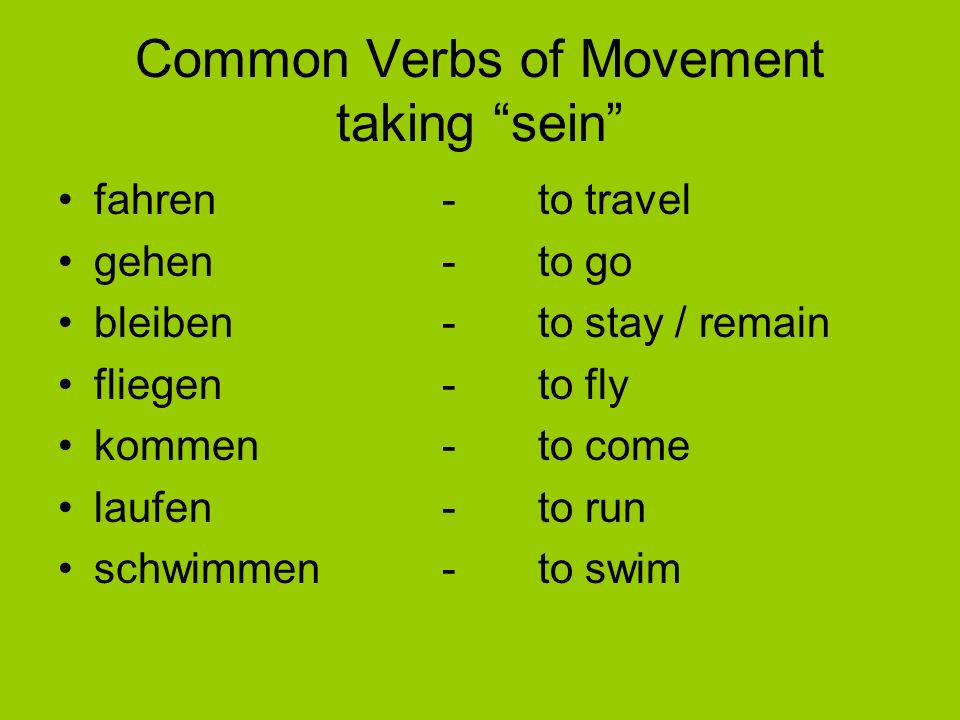

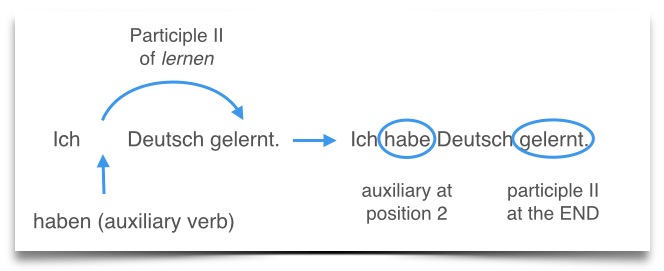

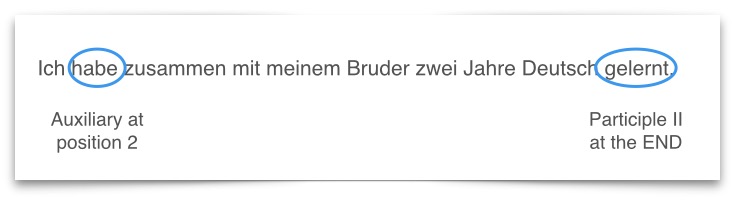

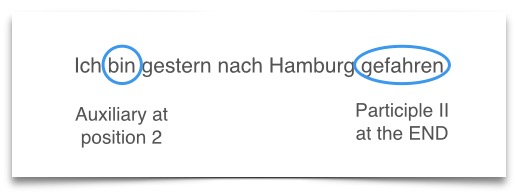

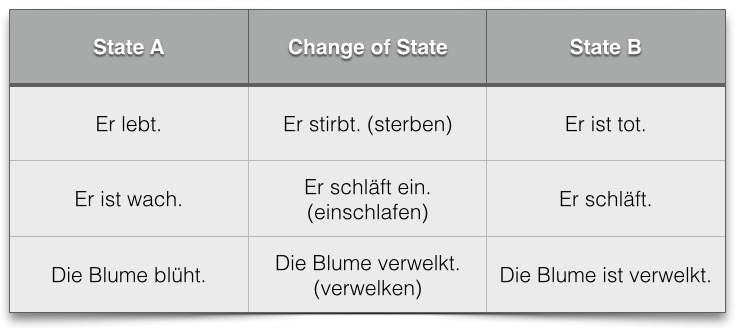

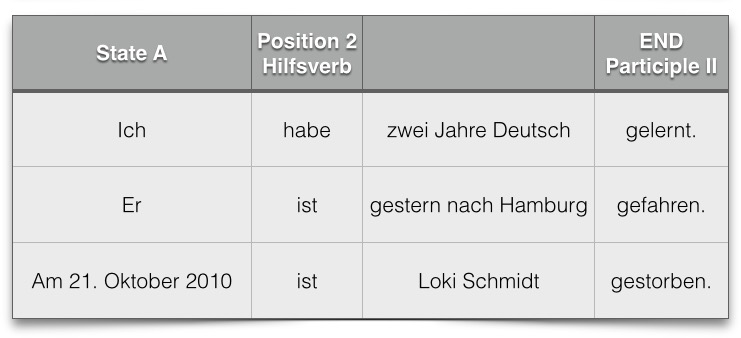

The Differences Between ‘Sein’ and ‘Haben’ in German

The Differences Between ‘Sein’ and ‘Haben’ in German

Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

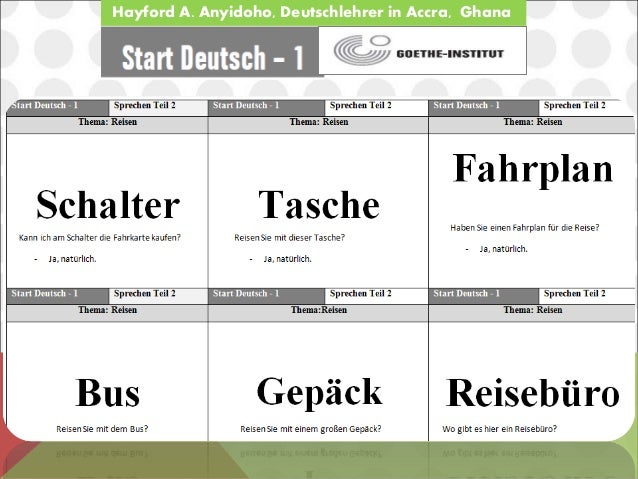

German Speaking Test Hints for A2, B1

German Speaking Test Hints for A2, B1

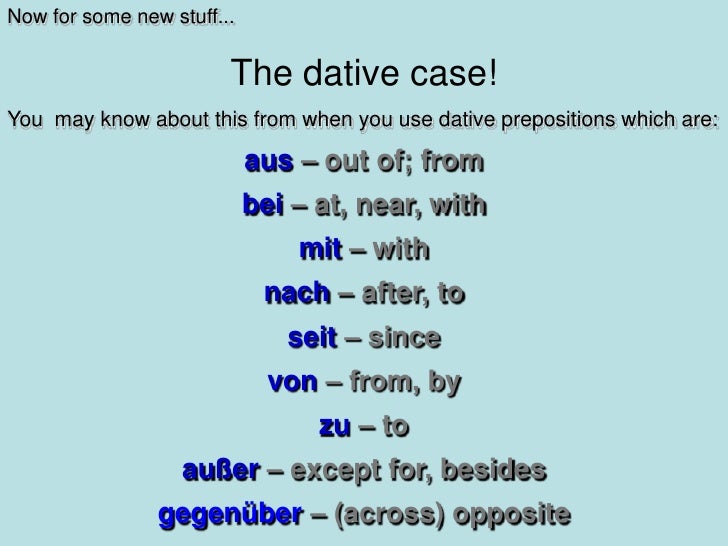

bei, von, mit, ab, aus, gegenüber, nach, zu, seit

bei, von, mit, ab, aus, gegenüber, nach, zu, seit

Zu meiner Familie gehören vier Personen. Die Mutter bin ich und dann gehört natürlich mein Mann dazu. Wir haben zwei Kinder, einen Sohn, der sechs Jahre alt ist und eine dreijährige Tochter.

Wir wohnen in einem kleinen Haus mit einem Garten. Dort können die Kinder ein bisschen spielen. Unser Sohn kommt bald in die Schule, unsere Tochter geht noch eine Zeit lang in den Kindergarten. Meine Kinder sind am Nachmittag zu Hause. So arbeite ich nur halbtags.

Eigentlich gehören zu unserer Familie auch noch die Großeltern. Sie wohnen nicht bei uns. Sie haben ein Haus in der Nähe. Die Kinder gehen sie oft besuchen.

Zu meiner Familie gehören vier Personen. Die Mutter bin ich und dann gehört natürlich mein Mann dazu. Wir haben zwei Kinder, einen Sohn, der sechs Jahre alt ist und eine dreijährige Tochter.

Wir wohnen in einem kleinen Haus mit einem Garten. Dort können die Kinder ein bisschen spielen. Unser Sohn kommt bald in die Schule, unsere Tochter geht noch eine Zeit lang in den Kindergarten. Meine Kinder sind am Nachmittag zu Hause. So arbeite ich nur halbtags.

Eigentlich gehören zu unserer Familie auch noch die Großeltern. Sie wohnen nicht bei uns. Sie haben ein Haus in der Nähe. Die Kinder gehen sie oft besuchen.

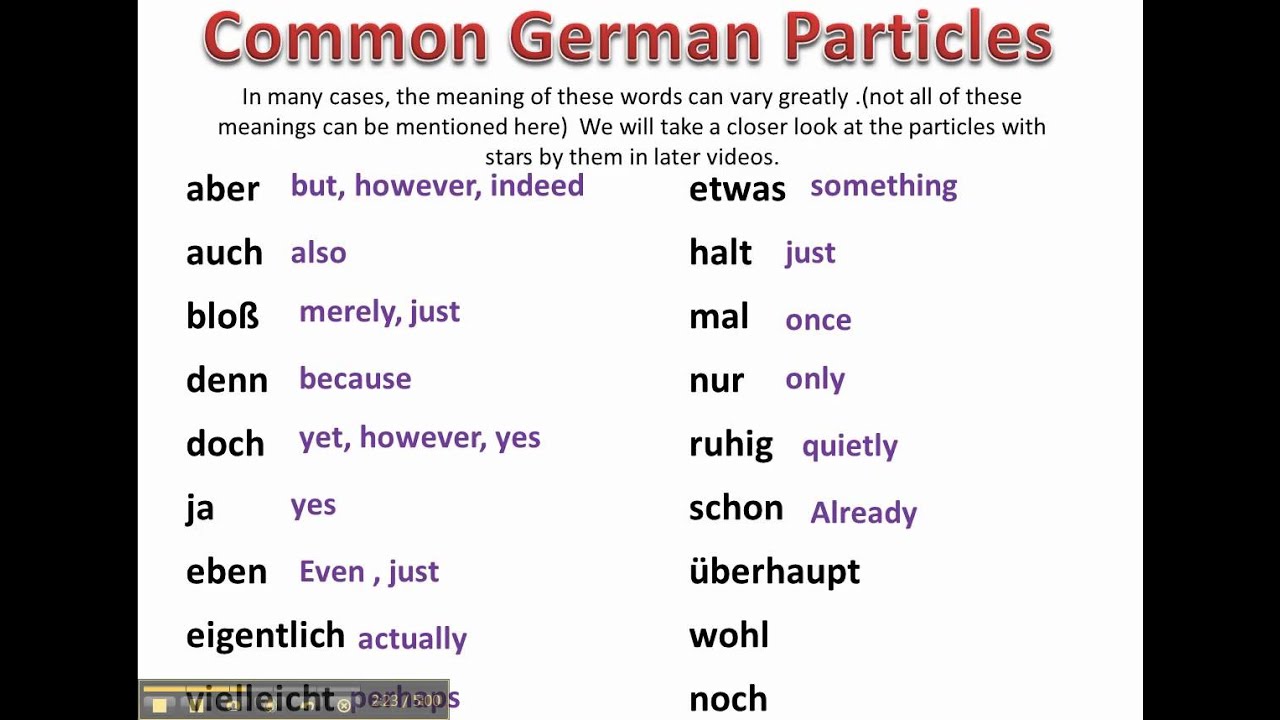

This example combines two particles (doch and mal) and is a very commonly used phrase.

“Kanzlerin Merkel ist aber jeder Montag betrunken!” (But Chancellor Merkel is drunk every Monday!)

In this example, you’ll notice that the word aber, or “but,” is a lot more flexible than its direct English translation. It can be placed in the sentence differently and has more shades of meaning than the simple English “but.” Discover some of its other meanings below!

Halt, eben, einmal* (in this context, always unshortened) and nun einmal (shortened: nun mal) imply that the (often unpleasant) fact expressed in a sentence cannot be changed and must be accepted. Halt and nun mal are more colloquial than eben. In English, they could be rendered to “as a matter of fact” or by a “happen to” construction.

This example combines two particles (doch and mal) and is a very commonly used phrase.

“Kanzlerin Merkel ist aber jeder Montag betrunken!” (But Chancellor Merkel is drunk every Monday!)

In this example, you’ll notice that the word aber, or “but,” is a lot more flexible than its direct English translation. It can be placed in the sentence differently and has more shades of meaning than the simple English “but.” Discover some of its other meanings below!

Halt, eben, einmal* (in this context, always unshortened) and nun einmal (shortened: nun mal) imply that the (often unpleasant) fact expressed in a sentence cannot be changed and must be accepted. Halt and nun mal are more colloquial than eben. In English, they could be rendered to “as a matter of fact” or by a “happen to” construction.

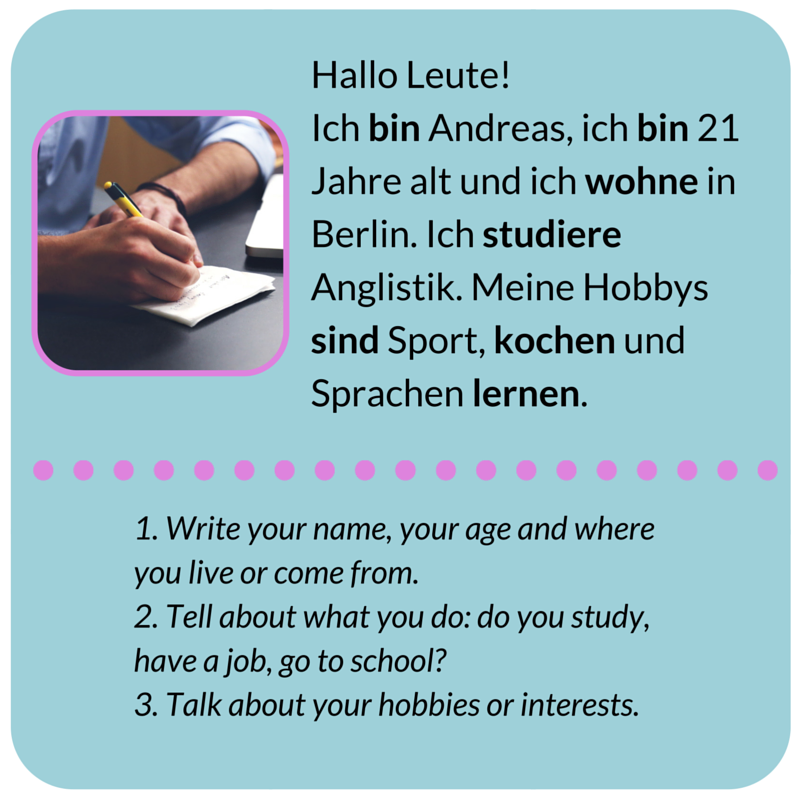

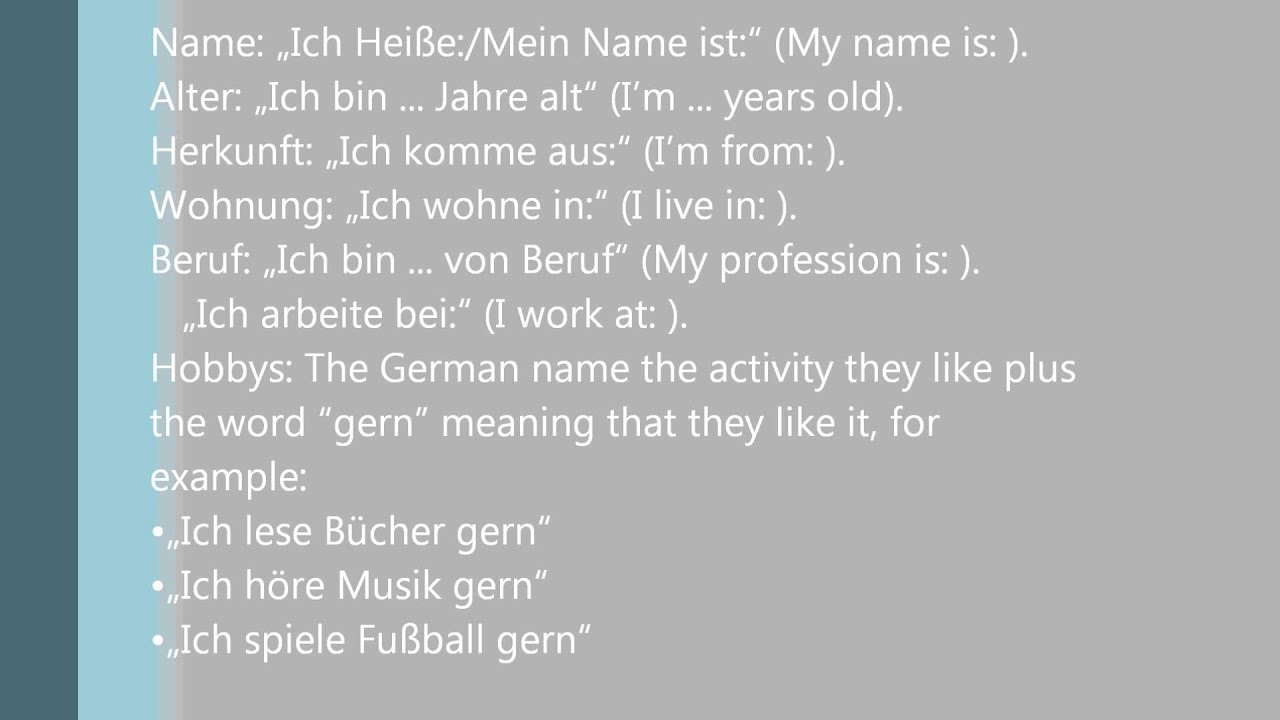

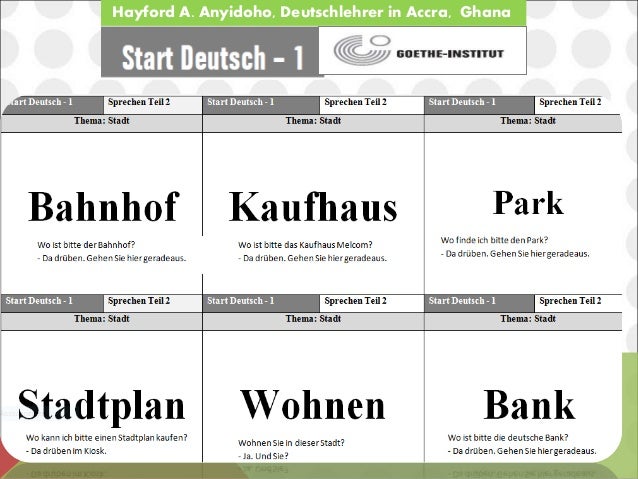

– Hi Guys! Hallo Leute!

– Oral Part – Start Deutsch 1 – Goethe Institut

– Hi Guys! Hallo Leute!

– Oral Part – Start Deutsch 1 – Goethe Institut

– Introducing Yourself

– Hallo, ich heiße Jenny Schubert. Ich bin 29 Jahre alt und ich komme aus Deutschland. Ich wohne

in Lohmar. Meine Hobbys sind schwimmen, Rad fahren und mit meinen Hunden spazieren gehen.

Ich arbeite als Übersetzerin. Ich spreche Tamil, Telugu, English und ein bisschen Deutsch.

– Können Sie bitte Ihren Namen buchstabieren?

– J – E – N – N – Y

– Und der Nachname: S – C – H – U – B – E – R – T

– Wie ist Ihre Telefonnummer?

– Meine Telefonnummer ist 777 888 999.

– Ich heiße…

– Ich bin…

– Ich heiße Jenny Schubert.

– Ich bin Jenny Schubert.

– Ich bin XX Jahre alt.

– Ich bin 29 Jahre alt.

– Ich komme aus…

– Introducing Yourself

– Hallo, ich heiße Jenny Schubert. Ich bin 29 Jahre alt und ich komme aus Deutschland. Ich wohne

in Lohmar. Meine Hobbys sind schwimmen, Rad fahren und mit meinen Hunden spazieren gehen.

Ich arbeite als Übersetzerin. Ich spreche Tamil, Telugu, English und ein bisschen Deutsch.

– Können Sie bitte Ihren Namen buchstabieren?

– J – E – N – N – Y

– Und der Nachname: S – C – H – U – B – E – R – T

– Wie ist Ihre Telefonnummer?

– Meine Telefonnummer ist 777 888 999.

– Ich heiße…

– Ich bin…

– Ich heiße Jenny Schubert.

– Ich bin Jenny Schubert.

– Ich bin XX Jahre alt.

– Ich bin 29 Jahre alt.

– Ich komme aus…

– Ich komme aus Deutschland. Ich komme aus Indien. Ich komme aus Schweden. Ich komme aus

Frankreich.

– Die USA

– Ich komme aus den USA. Ich komme aus der Türkei. Ich komme aus der Schweiz.

– Ich arbeite als Sekretärin. Ich arbeite als Ärztin.

– Ich bin Arzt von Beruf. Ich bin Ingenieur von Beruf.

– Ich spreche…

– Ich spreche Deutsch und Englisch.

– Ich spreche Türkisch, Russisch und ein bisschen Deutsch

– Meine Hobbys sind Karate, Tanzen und Schwimmen.

– Ich schwimme gern. Ich tanze gern. Ich fahre gern Fahrrad.

– Meine Hobbys sind…

– Ich wohne in…

– Ich wohne in Berlin. Ich wohne in Madrid. Ich wohne in Chicago.

– Danke schön fürs Zusehen und bisc

– Ich komme aus Deutschland. Ich komme aus Indien. Ich komme aus Schweden. Ich komme aus

Frankreich.

– Die USA

– Ich komme aus den USA. Ich komme aus der Türkei. Ich komme aus der Schweiz.

– Ich arbeite als Sekretärin. Ich arbeite als Ärztin.

– Ich bin Arzt von Beruf. Ich bin Ingenieur von Beruf.

– Ich spreche…

– Ich spreche Deutsch und Englisch.

– Ich spreche Türkisch, Russisch und ein bisschen Deutsch

– Meine Hobbys sind Karate, Tanzen und Schwimmen.

– Ich schwimme gern. Ich tanze gern. Ich fahre gern Fahrrad.

– Meine Hobbys sind…

– Ich wohne in…

– Ich wohne in Berlin. Ich wohne in Madrid. Ich wohne in Chicago.

– Danke schön fürs Zusehen und bisc

]]>

]]>