Modal Particles in German and their functions:

The role of Modal Particles in German

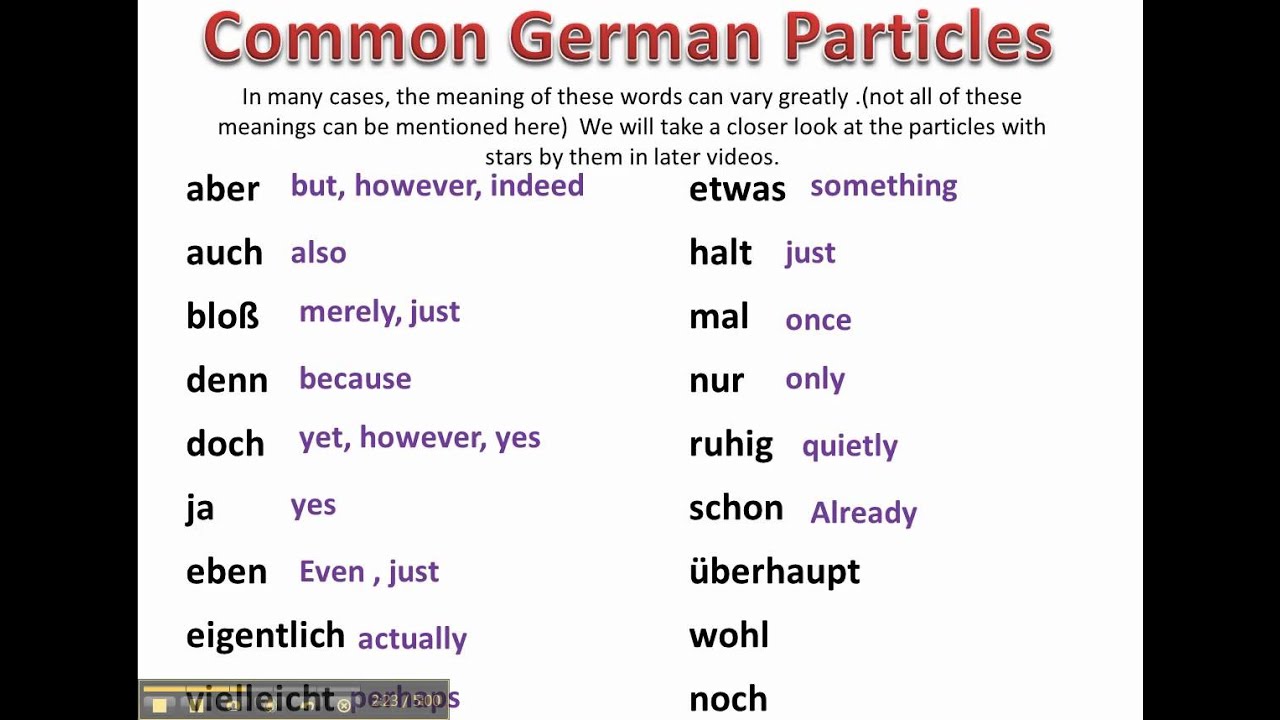

In the German language, a modal particle (German: Modalpartikel or Abtönungspartikel) is an uninflected word used mainly in spontaneous spoken language in colloquial registers. It has a dual function: reflecting the mood or attitude of the speaker or narrator, and highlighting the sentence focus. A modal particle’s effect is often vague and dependent on the overall context. Speakers often use them somewhat excessively, and sometimes combine several particles, as in doch mal, ja nun, or ja doch nun mal. They are a feature typical of the spoken language.So, What Are Modal Particles, Anyway?

Modal particles, also commonly just called “particles,” are words that don’t change grammatical meaning but still add a conditional change to a sentence. They are, in a sense, flavoring words that add a deeper element to language. In German, these could be words that soften the harshness of a comment, add a persuasive or suggestive element to a request or otherwise add subtle meaning to a sentence without changing the grammatical context.How do Particles Work?

Most of the time, particles are only used in spoken contexts. However, in the digital age, they’re also commonly used in German social media, due to the informality of the medium, so you can take advantage of this in your learning.Modal Particles

“Particle” is a catch-all term for words that have no clear part of speech, like “hmm.” (Many English particles are also described as “interjections.”) A modal particle is a word that’s used in speech to convey extra emphasis or emotion, without any real grammatical function.

It’s often said that English has no modal particles, but we have some pretty similar features. Think of asking a small child “What have you got there?” or “What’s your name then?” The there and then aren’t really necessary in those sentences, they’re just a friendly way of expressing interest. Or if you say “Come on now!” to express disbelief or frustration, the now isn’t strictly necessary.

In any case, the exact definition of a modal particle is complicated, but hopefully you’re getting the idea. For our purposes, let’s just define them as any common verbal flourish in spoken German

aber sicher!: most certainly

wohl: Das ist wohl wahr! That’s certainly true!

ja : Das ist ja eine tolle idee! That’s really a great idea !

na : Na klar komme ich! You bet I‘m coming!

Na logisch!: Of course!Contradiction/Disagreement

doch :Du bist doch nur zugekifft. You’re just [saying that because you’re] high.

Q: Das ist doch nicht dein Ernst, oder? A: Doch!

Q: You’re not being serious, are you? A: I am! Special Emphasis/Focus

gerade : Dass ich das gerade von DIR höre…

That I’m hearing that from YOU (of all people)…

| Affirmation/ Agreement | aber | aber gerne! with pleasure! |

Gerade heute musste es schneien!

It had to snow today (of all days)!eben: Ich versuche, eine Antwort auf eben die Frage zu formulieren.

I’m trying to find an answer to [just] that very question.Resignation ebenSo ist es eben. / Es ist eben so.

That’s just how it is.

naja: Naja, was hast du erwartet?Ah well, what did you expect?

halt : Ich war halt besoffen.

(What can i say?) I was drunk.Surprise

aber : Das war aber nett von dir!

That was nice of you! [I wasn’t expecting it]

etwa :Ist das etwa für mich? Is that for me?Interest

denn :Wie alt bist du denn? [to a child] So how old are you?

mal : Guck dir das mal an! Take a look at that! Intensifiers

schon : Das ist schon viel! It’s more than you think/more than it seems

ja : Du bist ja blöd! Are you ever dumb!

aber: Das ist aber völliger Quatsch! That’s complete nonsense! Exasperation/Anger

nur: Wie konntest du nur? How COULD you?

Was hat er sich nur dabei gedacht?

What WAS he thinking?

schon: Was will er schon von mir?

What in the world does he want from me?

nun: Was soll das nun bedeuten? Now what’s that supposed to mean? Softening/Casual

halt: Es war halt ein Vorschlag. It was just a suggestion.

mal: Warte mal. Wait a sec.

A lot of the time, the particle will follow the verb in the sentence—however, some come at the end.

“Die Katze ist ja schon gefüttert worden!” (The cat has already been fed!)

Here, the word ja is being used as a particle, reinforcing the fact that the cat has been fed, and follows the verb.

“Versuch’s doch mal!” (Come on, try it!)

Gerade heute musste es schneien!

It had to snow today (of all days)!eben: Ich versuche, eine Antwort auf eben die Frage zu formulieren.

I’m trying to find an answer to [just] that very question.Resignation ebenSo ist es eben. / Es ist eben so.

That’s just how it is.

naja: Naja, was hast du erwartet?Ah well, what did you expect?

halt : Ich war halt besoffen.

(What can i say?) I was drunk.Surprise

aber : Das war aber nett von dir!

That was nice of you! [I wasn’t expecting it]

etwa :Ist das etwa für mich? Is that for me?Interest

denn :Wie alt bist du denn? [to a child] So how old are you?

mal : Guck dir das mal an! Take a look at that! Intensifiers

schon : Das ist schon viel! It’s more than you think/more than it seems

ja : Du bist ja blöd! Are you ever dumb!

aber: Das ist aber völliger Quatsch! That’s complete nonsense! Exasperation/Anger

nur: Wie konntest du nur? How COULD you?

Was hat er sich nur dabei gedacht?

What WAS he thinking?

schon: Was will er schon von mir?

What in the world does he want from me?

nun: Was soll das nun bedeuten? Now what’s that supposed to mean? Softening/Casual

halt: Es war halt ein Vorschlag. It was just a suggestion.

mal: Warte mal. Wait a sec.

A lot of the time, the particle will follow the verb in the sentence—however, some come at the end.

“Die Katze ist ja schon gefüttert worden!” (The cat has already been fed!)

Here, the word ja is being used as a particle, reinforcing the fact that the cat has been fed, and follows the verb.

“Versuch’s doch mal!” (Come on, try it!)

This example combines two particles (doch and mal) and is a very commonly used phrase.

“Kanzlerin Merkel ist aber jeder Montag betrunken!” (But Chancellor Merkel is drunk every Monday!)

In this example, you’ll notice that the word aber, or “but,” is a lot more flexible than its direct English translation. It can be placed in the sentence differently and has more shades of meaning than the simple English “but.” Discover some of its other meanings below!

Halt, eben, einmal* (in this context, always unshortened) and nun einmal (shortened: nun mal) imply that the (often unpleasant) fact expressed in a sentence cannot be changed and must be accepted. Halt and nun mal are more colloquial than eben. In English, they could be rendered to “as a matter of fact” or by a “happen to” construction.

This example combines two particles (doch and mal) and is a very commonly used phrase.

“Kanzlerin Merkel ist aber jeder Montag betrunken!” (But Chancellor Merkel is drunk every Monday!)

In this example, you’ll notice that the word aber, or “but,” is a lot more flexible than its direct English translation. It can be placed in the sentence differently and has more shades of meaning than the simple English “but.” Discover some of its other meanings below!

Halt, eben, einmal* (in this context, always unshortened) and nun einmal (shortened: nun mal) imply that the (often unpleasant) fact expressed in a sentence cannot be changed and must be accepted. Halt and nun mal are more colloquial than eben. In English, they could be rendered to “as a matter of fact” or by a “happen to” construction.

- Gute Kleider sind eben teuer. (“Good clothes are expensive, it can’t be helped.”/”Good clothes happen to be expensive.”)

- Er hat mich provoziert, da habe ich ihn halt geschlagen. (“He provoked me, so I hit him – what did you expect?”)

- Es ist nun einmal so. (“That’s just how it is.”)

- Ich habe ihm ein Buch geschenkt, er liest ja sehr gerne. (“I gave him a book; as you know he likes to read.”)

- Ich verleihe kein Geld, das zerstört ja nur Freundschaften. (“I never lend money. Everyone knows that only destroys friendships.”)

- “Hör mal zu!” (Listen!” or “Listen to me”!)

- “Beeile dich mal!” (“Do hurry up!”)

- Sing mal etwas Schönes! (“Why don’t you sing something pretty?”)

- Schauen wir mal. (lit.: “Let’s take one look.” meaning: “Let’s just relax and then we’ll see what we’ll be doing.”)

- Gehst Du nicht nach Hause? Doch, ich gehe gleich. (“Are you not going home?” “Oh, yes, I am going in a moment”.) (Affirmation of a negative question; obligatory.)

- Komm doch her! (“Do come here!”) (Emphatically)

- Komm doch endlich her! (“Do come on! Get a move on!”) (More emphatically and impatiently)

- Ich habe dir doch gesagt, dass es nicht so ist. (“I did tell you that it’s not like that.”)

- Ich kenne mich in Berlin aus. Ich war doch letztes Jahr dort. (“I know my way around Berlin. I was here last year, after all/as a matter of fact.”)

- Ich war schon auf der Party, aber Spaß hatte ich nicht. (“I was indeed at the party, but I did not enjoy myself.”)

- Ich war schon (/bereits) auf der Party, aber Spaß hatte ich (noch) nicht. (“I was already at the party, but I had not (yet) been enjoying myself.”)

- Du bist also doch gekommen! (“You came after all.”)

- Ich sehe nicht viel fern, aber wenn etwas Gutes kommt, schalte ich doch ein. (“I don’t watch much TV, but I do tune in if something good comes on.”)

- Du sprichst aber schon gut Deutsch! (“But you do already speak good German!”)

- Ich hab ihm eh gesagt, dass er sich wärmer anziehen soll. (“I told him to put on warmer clothes in the first place.”)

- Das ist eh nicht wahr. (“That’s not true anyway.”)

- Das ist vielleicht ein großer Hund! (with an emphasis on “Das”, “That’s quite a large dog!”)

- Vielleicht ist das ein großer Hund. Es ist schwer zu erkennen. (“Maybe that’s a large dog. It’s difficult to tell.”)

- Des kôsch fei net macha! (Swabian) = Das kannst du (eigentlich wirklich) nicht machen. (You can’t do that! / If you do look at it, you really can’t do that. / You can’t, I should think, do that.)

- I bin fei ned aus Preissen! (Bavarian) = Ich bin, das wollte ich nur einmal anmerken, nicht aus Preußen. (Just to mention, I’m not from Prussia.)

- Es wird wohl Regen geben. (“It looks like rain. / It’s probably going to rain.”)

- Du bist wohl verrückt!. (“You must be out of your mind.”)