Dutch lessons-Personal Pronouns, Nouns

Dutch Personal Pronouns

| Singular | ||

| Person | Dutch | English |

| 1st | ik | I |

| 2nd | je (unstressed), jij (stressed) | you (informal) |

| 2nd | u | you (formal) |

| 3rd | hij | he |

| 3rd | ze (unstressed), zij(stressed) | she |

| 3rd | het | it |

| Plural | ||

| Person | Dutch | English |

| 1st | we (unstressed), wij (stressed) | we |

| 2nd | jullie | you (informal) |

| 2nd | u | you (formal) |

| 3rd | ze (unstressed), zij (stressed) | they |

| Dutch | English |

| ik ben | I am |

| je bent (ben je?) | you are (informal, unstressed) |

| jij bent (ben jij?) | you are (informal, stressed) |

| u bent (bent u?) | you are (formal) |

| hij is | he is |

| ze is | she is (unstressed) |

| zij is | she is (stressed) |

| het is | it is |

| we zijn | we are (unstressed) |

| wij zijn | we are (stressed) |

| jullie zijn | you are |

| ze zijn | they are (unstressed) |

| zij zijn | they are (stressed) |

Dutch Nouns and Gender

All nouns have a gender in Dutch, either common (de words) or neuter (het words). It is hard to guess which gender a noun is, so it is best to memorize the genders when memorizing vocabulary. However, two-thirds of Dutch words are common gender (because the common gender has combined the former feminine and masculine genders.) So it may be easier to memorize which nouns are neuter, and then assign common gender to the rest. All diminutives (words ending in -je) and infinitives used as nouns, as well as colors, metals, compass directions, and all words that end in -um, -aat, -sel, -isme are neuter. Most nouns beginning with ge- and ending with -te are neuter, as are most nouns beginning with ge-, be-, and ver-. Common noun endings include: -aar, -ent, -er, -es, -eur, -heid, -ij, -ing, -teit, -tie.Articles & Demonstratives

Singular “the” Plural “the” Indefinite “a” or “an” The definite article is used more in Dutch than in English. It is always used before the names of the seasons, street names and in an abstract sense. There are some idioms that should be memorized, however: in het Nederlands (in Dutch), in de stad (in town), in het zwart (in black), met de auto (by car), met de tijd (in/with time); op tafel (on the table), in zee (in the sea), op kantoor (at the office), in bad (in the bath), op straat (in the street).

common neuter Singular this that deze die dit dat Plural these those Dutch Subject and Object Pronouns

I ik (‘k) me mij (me) you (singular familiar) jij (je) you jou (je) you (singular formal) u you u he hij him hem (‘m) she zij (ze) her haar (ze) it hij / het it het (‘t) we wij (we) us ons you (plural familiar) jullie you jullie (je) you (plural formal) u you u they zij (ze) them hen (ze) / hun (ze) Unstressed forms (shortened forms used mostly in the spoken language) are in parentheses. There are also unstressed forms of ik (‘k), hij (ie) and het (‘t) but these are not written in the standard language. You will see them in informal writing, however (such as on internet forums or sometimes in film subtitles.)

Direct and indirect object pronouns are the same in Dutch, except for “them.” Hen is used if it is a direct object, and hun is used if it is an indirect object. Generally, indirect objects are preceded by “to” or “from” in English, and direct objects are not preceded by any prepositions. Additionally, these object pronouns are used after prepositions.

An alternative way of showing possession without using the possessive pronouns is to use van + object pronoun. In fact, this is the only way to show possession with the jullie form, as there is no possessive pronoun for it. This construction corresponds to “of + object” and occurs often in sentences with the verb “to be.” Is deze pen van jou? Is this your pen? Die schoenen zijn niet van mij. Those shoes are not mine.

If the noun is not present in the clause, then die or dat + van + object pronoun is used. Mijn huis is klein; dat van hem is erg groot. My house is small; his is very large.

Dutch Verbs To Be & to Have – Zijn and Hebben

Present tense of zijn – to be(zayn)

I am ik ben ik ben we are wij zijn vay zayn you are jij / u bent yay / ew bent you are jullie zijn yew-lee zayn he, she, it is hij, zij, het is hay, zay, ut is they are zij zijn zay zayn Present tense of hebben – to have(heh-buhn)

I have ik heb ik hep we have wij hebben vay heh-buhn you have jij / u hebt yay / ew hept you have jullie hebben yew-lee heh-buhn he, she, it is hij, zij, het heeft hay, zay, ut hayft they have zij hebben zay heh-buhn U heeft rather than u hebt is also possible.

Past tense of zijn – to be(zayn)

I was ik was ik vas we were wij waren vay vah-ruhn you were jij / u was yay / ew vas you were jullie waren yew-lee vah-ruhn he, she, it was hij, zij, het was hay, zay, ut vas they were zij waren zay vah-ruhn Past tense of hebben – to have(heh-buhn)

I had ik had ik haht we had wij hadden vay hah-duhn you had jij / u had yay / ew haht you had jullie hadden yew-lee hah-duhn he, she, it had hij, zij, het had hay, zay, ut haht they had zij hadden zay hah-duhn You must use the subject pronouns; however, I will leave them out of future conjugations since most verbs only have two forms for each conjugation.

Expressions with zijn and hebben: Het/dat is jammer – It’s/that’s a pity jarig zijn – to have a birthday kwijt zijn – to have lost op het punt staan – to be about to van plan zijn – to intend voor elkaar zijn – to be in order honger / dorst hebben – to be hungry / thirsty gelijk hebben – to be right haast hebben – to be in a hurry het hebben over – to talk about het druk hebben – to be busy het koud hebben / warm – to be cold / warm last hebben van – to be bothered by nodig hebben – to need slaap hebben – to be sleepy zin hebben in – to feel likeThe Complete Guide to Dutch Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns are words such as I, me, your and it, words which are used to refer to a specific person or actor without having to mention them explicitly. Pronominal forms are a key element of all languages and must be learned early in one’s linguistic journey in order to communicate effectively. This article discusses Dutch personal pronouns and provides an overview of all key information.Personal pronouns

The below table delineates the basic Dutch personal pronoun system:For the most part, Dutch personal pronouns follow a similar pattern to English. They have the same distinctions for masculine, feminine and neuter and for first, second and third person. They also have the same distinctions for nominative and accusative, depending on whether the pronoun is used as subject or object of the clause.

Nominative Accusative Ik I Mij /me Me Jij/je You Jou/je You U You (formal) U You (formal) Hij/-ie He Hem Him Zij/ze She Haar Her Het It Het It Wij/We We Ons Us Jullie You (plural) Jullie You (plural) Ze They Hen/Ze Them Some Dutch pronouns have two versions as outlined in the table below:

These are generally interchangeable, but the first variant can be used for emphasis or when introducing the person for the first time. The exception is the ie variant of ‘he’, which can only be used in subordinate constructions, such as in subordinate clauses or in questions. It is usually marked with a dash in order to show that it is not a typical pronoun. This construction is very informal. Komt-ie? ‘Is he coming?’ Ik ben bang dat-ie weg is. ‘I’m afraid he has gone’

Jij/je You Hij/-ie He Zij/ze She/they Wij/we We The distinction between u en jij.

Both u and jij mean ‘you’ (singular), but u is the more formal variant. Theoretically, u is used when addressing people you do not know, or with clients or people in authority. However, Dutch culture is generally quite egalitarian and it rare to hear u in everyday speech. You might use it when interacting with a client, for example, but even then, this might only be restricted to the first interaction. By the end of the conversation, it is common to have switched to jij entirely. Young people tend always to use jij with each other.Possessive pronouns

The table below shows the possessive pronoun system of Dutch:There are different forms of the first person possessive pronouns depending on whether it is singular or plural.

Mijn/mijne My Jouw/jouwe Your Uw/uwe Your (formal) Zijn His Haar Her Ons/onze Our Jullie Your (plural) Hun Their Where the noun is singular, the bare possessive pronoun is used, without any ending. Where the noun is plural, an –e ending is added to the pronoun. Often, when you hear Dutch people speak English, you will notice that they will sometimes produce utterances such as ‘John his car’ or ‘Maria her hat’. This is a direct transfer of a possessive construction that is commonly used in spoken Dutch. Jan z’n fiets. Jan’s bicycle Tinneke d’r tuin. Tinneke’s garden. In these examples, z’n is a contractions of zijn and d’r is a contraction of haar. Some Dutch learners of English understand the ‘s which marks possession is an abbreviation of his, as it is in the Dutch construction. So when they use the construction for feminine possessors, they use her, in Dutch haar.

Singular Plural Mijn huis My house Mijne huizen My houses Ons auto Our car Onze autos Our cars Ons paard Our horse Onze paarden Our horses Mijn potlood My pencil Mijne potloden My pencils The third person singular

The third person pronoun het is most commonly used for inanimate nouns, both in the nominative and accusative. It corresponds to English it. Het is drie uur. It is three o’ clock. Ik heb het al gedaan. I have already done it. Het was echt leuk. It was really good fun. Hij (nominative) and hem (accusative) are most commonly used when the noun is masculine and animate. They correspond to English ‘he’ and ‘him’. Hij is mijn stiefvader. He is my stepfather. Hij and hem can also be used when the noun is a common gender noun. In the accusative, it often takes the contracted form ‘m. Ik kan mijn lamp niet vinden. Heb je‘m gezien? ‘I can’t find my lamp. Have you seen it?’ Ik vind je tafel echt leuk. Waar heb je hem gekocht? ‘I really like your table. Where did you buy it?’ Ik vond de oogschaduw mooi, maar hij was echt duur. ‘I really liked the eyeshadow, but it was very expensive.’Feminine pronouns

We generally can only use the feminine pronouns when referring to feminine animate nouns. Zij is de nieuwe manager van de bedrijf. ‘She is the new manager of the company’. However, there is a growing tendency to use feminine pronouns with certain collective nouns, which denote larger organisations. This is particularly the case for haar, meaning ‘her’. De Commissie en haar personeel hebben een groot rol gespeeld. ‘The Commission and its (her) staff have played a big role’. De vereniging heeft laten weten dat zijzich gesteund voelt door haarvrijwillgers. ‘The organisation has let it be known that it (she) feels supported by its (her) volunteers‘. The distinction in grammatical gender between masculine and feminine has all but disappeared in the Dutch language. Both masculine and feminine nouns are denoted by the article de. Possessive pronouns zijn and haar should technically only be used with de words that were originally masculine and feminine, respectively, but this is no longer a meaningful distinction for most Dutch speakers. It is increasingly common to find haar used with neuter het nouns, but grammar purists would consider this incorrect. Het kabinet heeft haar plannen over studiefinanciering bekend gemaakt. ‘The cabinet has made its (her) plans for student financing known’. The use of haar in this way has become so pervasive that it is sometimes known as the haar-ziekte, or the ‘her disease’.Dutch Pronouns Grammar Challenge

This article has outlined the basic pronominal distinctions in Dutch. Now that you know the basics, why not give the Dutch pronoun grammar challenges a try? Practice using Dutch pronouns in actual sentences with Clozemaster!How to form plural nouns in Dutch

Most plural nouns are formed by adding either -en or -s. Remember that the definite article is always de before plural nouns.

1. -en (the n is pronounced softly) is added to most nouns, with a few spelling changes

boek – boeken book(s) jas – jassen coat(s) haar – haren hair(s) huis – huizen house(s)

Spelling changes: Words with long vowels (aa, ee, oo, and uu) drop the one vowel when another syllable is added. Words with the short vowels (a, e, i, o and u) double the following consonant to keep the vowels short. The letters f and s occur at the end of words or before consonants, while the letters v and z occur in the middle of words before vowels. (These spelling rules are also used for conjugating verbs, so it’s best to memorize them as soon as possible.)

2. -s is added to nouns ending in the unstressed syllables -el, -em, -en, and -er (and -aar(d), -erd, -ier when referring to people), foreign words and to most nouns ending in an unstressed vowel

tafel – tafels table(s) jongen – jongens boy(s) tante – tantes aunt(s) bakker – bakkers baker(s)

Nouns ending in the vowels -a, -o, and -u add an apostrophe before the s: foto’s, paraplu’s

Irregular forms

3. Some nouns containing a short vowel do not double the following consonant in the plural before -en. The plural vowel is then pronounced as long.

bad – baden bath(s) dag – dagen day(s) spel – spelen game(s) (like the Olympics, smaller games are spellen) glas – glazen glass(es) weg – wegen road(s)

4. A few neuter nouns take the ending -eren (or -deren if the noun ends in -n)

blad – bladeren leaf (leaves) kind – kinderen child(ren) ei – eieren egg(s) been – beenderen bone(s) [Note: been – benen leg(s)] lied – liederen song(s) volk – volkeren nation(s), people

5. Nouns ending in -heid have a plural in -heden.

mogelijkheid – mogelijkheden possibility (possibilities)

6. Some other common irregular plurals are:

stad – steden town(s) schip – schepen ship(s) lid – leden member(s) koe – koeien cow(s)

Dutch Possessives: Adjectives and Pronouns

Singular Plural mijn (m’n) my ons / onze our jouw (je) your (informal) jullie (je) your (informal) uw your (formal) uw your (formal) zijn (z’n) his hun their haar her zijn (z’n) its Ons is used before singular neuter/het nouns, and onze is used elsewhere (before singular common/de nouns, and all plural nouns.) Je, the unstressed form of jouw, is commonly used in spoken and written Dutch, unless the speaker/writer wants to stress the pronoun. In the plural,jullie is the norm, unless jullie has already been used in the sentence, then je is used to avoid the redundancy. The other unstressed forms are not commonly written in the standard language, but are commonly spoken and written in informal communication.

Like in English, Dutch possessive adjectives are used in front of a noun to show possession: mijn boek (my book). There are a few ways to express the -‘s used in English too. -s can be added to proper names and members of the family: Jans boek (John’s book) The preposition vancan be used to mean of: het boek van Jan (the book of John = John’s book) And in more colloquial speech, the unstressed forms in parentheses above (agreeing in gender and number) can be used in place of the -s: Jan z’n boek (John’s book)

To form the possessive pronouns, add -e to the stressed forms (except for jullie) and use the correct article. The only way to show possession with jullie is to use van jou (literally meaning “of you”), although all the others can be used with van too.

de/het mijne, jouwe, uwe, zijne, hare, onze, hunne (mine, yours, yours, his/its, hers, ours, theirs)

]]>Dutch An Essential Grammar Integral Dutch CourseDutch Links

Dutch Course 1 Dutch Video Course 2 Dutch Complete 3Dutch Downloads

Spoken French[/caption]

Spoken French[/caption]

]]>

]]>

The Conditional

The conditional is not a tense because it does not refer to a time period. Instead, the conditional is a mood that expresses what a subject would do under certain circumstances.

Use the conditional in the following situations:

The Conditional

The conditional is not a tense because it does not refer to a time period. Instead, the conditional is a mood that expresses what a subject would do under certain circumstances.

Use the conditional in the following situations:

The conditional uses the same stem as the future tense, but you then add the conditional endings, which are exactly the same as the imperfect endings, as shown in Table 1.

For irregular verbs and verbs with spelling changes, you simply add conditional endings to the stems used for the future.

The conditional uses the same stem as the future tense, but you then add the conditional endings, which are exactly the same as the imperfect endings, as shown in Table 1.

For irregular verbs and verbs with spelling changes, you simply add conditional endings to the stems used for the future.

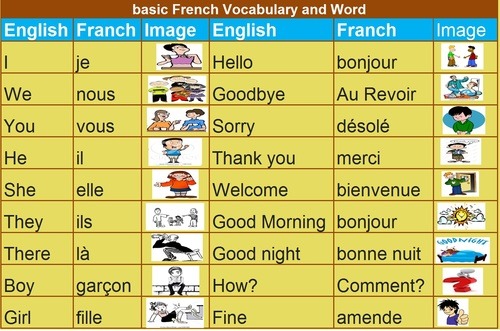

Future Tense

The future tense expresses what the subject will do or is going to do in the future. It also describes what action will or is going to take place at a future time.

Although the future tense is usually used for events taking place in the future, the present tense in French may be used to refer to an action that will take place very soon or to ask for future instructions.

Future Tense

The future tense expresses what the subject will do or is going to do in the future. It also describes what action will or is going to take place at a future time.

Although the future tense is usually used for events taking place in the future, the present tense in French may be used to refer to an action that will take place very soon or to ask for future instructions.

In addition, you can express an imminent action in the near future by conjugating the verb aller (to go) in the present tense and adding the infinitive of the action the speaker will perform. Keep in mind that the irregular present tense of aller is je vais, tu vas, il va, nous allons, vous allez, and ils vont.

In addition, you can express an imminent action in the near future by conjugating the verb aller (to go) in the present tense and adding the infinitive of the action the speaker will perform. Keep in mind that the irregular present tense of aller is je vais, tu vas, il va, nous allons, vous allez, and ils vont.

Note the following about forming the future tense of regular verbs:

Note the following about forming the future tense of regular verbs:

For verbs ending in e + consonant + er (but not é + consonant + er), change the silent e before the infinitive ending to è in all forms of the future tense.

For verbs ending in e + consonant + er (but not é + consonant + er), change the silent e before the infinitive ending to è in all forms of the future tense.

Negating in the future tense

To negate a sentence in the future, simply put ne and the negative word around the conjugated verb:

Negating in the future tense

To negate a sentence in the future, simply put ne and the negative word around the conjugated verb:

The passé composé, a compound past tense, is formed by combining two elements: when (the action has taken place and, therefore, requires the helping verb avoir) and what (the action that has happened and, therefore, requires the past participle of the regular or irregular verb showing the particular action). See Figure 1.

The passé composé, a compound past tense, is formed by combining two elements: when (the action has taken place and, therefore, requires the helping verb avoir) and what (the action that has happened and, therefore, requires the past participle of the regular or irregular verb showing the particular action). See Figure 1.

Here are some examples of the passé composé.

Elle a expliqué son problème. (She explained her problem.)

Ils ont réussi. (They succeeded.)

J’ai entendu les nouvelles. (I heard the news.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with avoir

In a negative sentence in the passé composé, ne precedes the helping verb, and the negative word (pas, rien, jamais, and so on follows it:

Je n’ai rien préparé. (I didn’t prepare anything.)

Nous n’avons pas fini le travail. (We didn’t finish the work.)

Il n’a jamais répondu à la lettre. (He never answered the letter.)

Questions in the passé composé with avoir

To form a question in the passé composé using inversion, invert the conjugated helping verb with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. Then place the negative around the hyphenated helping verb and subject pronoun:

As‐tu mangé? (Did you eat?)

N’as‐tu rien mangé? (Didn’t you eat anything?)

A‐t‐il attendu les autres? (Did he wait for the others?)

N’a‐t‐il pas attendu? (Didn’t he wait for the others?)

Here are some examples of the passé composé.

Elle a expliqué son problème. (She explained her problem.)

Ils ont réussi. (They succeeded.)

J’ai entendu les nouvelles. (I heard the news.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with avoir

In a negative sentence in the passé composé, ne precedes the helping verb, and the negative word (pas, rien, jamais, and so on follows it:

Je n’ai rien préparé. (I didn’t prepare anything.)

Nous n’avons pas fini le travail. (We didn’t finish the work.)

Il n’a jamais répondu à la lettre. (He never answered the letter.)

Questions in the passé composé with avoir

To form a question in the passé composé using inversion, invert the conjugated helping verb with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. Then place the negative around the hyphenated helping verb and subject pronoun:

As‐tu mangé? (Did you eat?)

N’as‐tu rien mangé? (Didn’t you eat anything?)

A‐t‐il attendu les autres? (Did he wait for the others?)

N’a‐t‐il pas attendu? (Didn’t he wait for the others?)

Dr. and Mrs. Vandertrampp live in the house in Figure , as illustrated in Table 1. Their name may help you memorize the 17 verbs using être. An asterisk (*) in Table 6 denotes an irregular past participle.

Verbs whose helping verb is être must show agreement of their past participles in gender (masculine or feminine — add e) and number (singular or plural — add s) with the subject noun or pronoun, as shown in Table 2 :

Remember the following rules when using être as a helping verb in the passé composé:

Vous can be a singular or plural subject for both masculine and feminine subjects.

Singular Plural

Vous êtes entré. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrés. (You entered.)

Dr. and Mrs. Vandertrampp live in the house in Figure , as illustrated in Table 1. Their name may help you memorize the 17 verbs using être. An asterisk (*) in Table 6 denotes an irregular past participle.

Verbs whose helping verb is être must show agreement of their past participles in gender (masculine or feminine — add e) and number (singular or plural — add s) with the subject noun or pronoun, as shown in Table 2 :

Remember the following rules when using être as a helping verb in the passé composé:

Vous can be a singular or plural subject for both masculine and feminine subjects.

Singular Plural

Vous êtes entré. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrés. (You entered.)

Vous êtes entrée. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrées. (You entered.)

For a mixed group, always use the masculine form.

Roger et Bernard sont revenus. (Roger and Bernard came back.)

Louise et Mireille sont revenues. (Louise and Mireille came back.)

Roger et Louise sont revenus. (Roger and Louise came back.)

If the masculine past participle ends in an unpronounced consonant, pronounce the consonant for the feminine singular and plural forms:

Il est mort. (He died.) Ils sont morts. (They died.)

Elle est morte. (She died.) Elles sont mortes. (They died.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with être

In the negative, put ne before the conjugated form of être and the negative word after it:

Il n’est pas sorti. (He didn’t go out.)

Elles ne sont pas encore arrivées. (They didn’t arrive yet.)

Questions in the passé composé with être

To form a question using inversion, invert the conjugated form of être with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. The negatives surround the hyphenated verb and pronoun:

Sont‐ils partis? (Did they leave?)

Ne sont‐ils pas partis? (Didn’t they leave?)

Vous êtes entrée. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrées. (You entered.)

For a mixed group, always use the masculine form.

Roger et Bernard sont revenus. (Roger and Bernard came back.)

Louise et Mireille sont revenues. (Louise and Mireille came back.)

Roger et Louise sont revenus. (Roger and Louise came back.)

If the masculine past participle ends in an unpronounced consonant, pronounce the consonant for the feminine singular and plural forms:

Il est mort. (He died.) Ils sont morts. (They died.)

Elle est morte. (She died.) Elles sont mortes. (They died.)

Forming the negative in the passé composé with être

In the negative, put ne before the conjugated form of être and the negative word after it:

Il n’est pas sorti. (He didn’t go out.)

Elles ne sont pas encore arrivées. (They didn’t arrive yet.)

Questions in the passé composé with être

To form a question using inversion, invert the conjugated form of être with the subject pronoun and add a hyphen. The negatives surround the hyphenated verb and pronoun:

Sont‐ils partis? (Did they leave?)

Ne sont‐ils pas partis? (Didn’t they leave?)

Verbs whose helping verb is être must show agreement of their past participles in gender (masculine or feminine — add e) and number (singular or plural — add s) with the subject noun or pronoun, as shown in Table 2 :

Verbs whose helping verb is être must show agreement of their past participles in gender (masculine or feminine — add e) and number (singular or plural — add s) with the subject noun or pronoun, as shown in Table 2 :

Remember the following rules when using être as a helping verb in the passé composé:

Vous can be a singular or plural subject for both masculine and feminine subjects.

Singular Plural

Vous êtes entré. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrés. (You entered.)

Vous êtes entrée. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrées. (You entered.)

For a mixed group, always use the masculine form.

Remember the following rules when using être as a helping verb in the passé composé:

Vous can be a singular or plural subject for both masculine and feminine subjects.

Singular Plural

Vous êtes entré. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrés. (You entered.)

Vous êtes entrée. (You entered.) Vous êtes entrées. (You entered.)

For a mixed group, always use the masculine form.

Framing Questions in French Using Est-Ce Que

Framing Questions in French Using Est-Ce Que

Conjugating Reflexive Verbs

A reflexive verb infinitive is identified by its reflexive pronoun se, which is placed before the infinitive and that serves as a direct or indirect object pronoun. A reflexive verb shows that the subject is performing the action upon itself and, therefore, the subject and the reflexive pronoun refer to the same person or thing, as in je m’appelle (I call myself), which is translated to “My name is.”

Conjugating Reflexive Verbs

A reflexive verb infinitive is identified by its reflexive pronoun se, which is placed before the infinitive and that serves as a direct or indirect object pronoun. A reflexive verb shows that the subject is performing the action upon itself and, therefore, the subject and the reflexive pronoun refer to the same person or thing, as in je m’appelle (I call myself), which is translated to “My name is.”

Some verbs must always be reflexive, whereas other verbs may be made reflexive by adding the correct object pronoun. The meaning of some verbs varies depending upon whether or not the verb is used reflexively.

Reflexive verbs are always conjugated with the reflexive pronoun that agrees with the subject: me (myself), te (yourself), se (himself, herself, itself, themselves), nous (ourselves), and vous (yourself, yourselves). These pronouns generally precede the verb. Follow the rules for conjugating regular verbs, verbs with spelling changes, and irregular verbs, depending on of the tense, as shown in Table 1:

Reflexive constructions have the following translations:

Some verbs must always be reflexive, whereas other verbs may be made reflexive by adding the correct object pronoun. The meaning of some verbs varies depending upon whether or not the verb is used reflexively.

Reflexive verbs are always conjugated with the reflexive pronoun that agrees with the subject: me (myself), te (yourself), se (himself, herself, itself, themselves), nous (ourselves), and vous (yourself, yourselves). These pronouns generally precede the verb. Follow the rules for conjugating regular verbs, verbs with spelling changes, and irregular verbs, depending on of the tense, as shown in Table 1:

Reflexive constructions have the following translations:

Consider the following most commonly used reflexive verbs. Those marked with asterisks have shoe verb spelling change within the infinitive.

Consider the following most commonly used reflexive verbs. Those marked with asterisks have shoe verb spelling change within the infinitive.

er (cut oneself)

er (cut oneself) Expressions of Quantity with Numbers or de

Expressions of Quantity with Numbers or de