The genitive case has four functions. It is widely rumored that the genitive case is falling out of usage in German. This statement only applies conditionally to certain functions of the genitive; these will be noted below.

1) Possession & relationships

The genitive case indicates that noun belongs to or bears some kind of relationship with someone or something. The genitive is rendered in English as a possessive with an

‘s or with the preposition

of.

EXAMPLES:

| Die Farbe meiner Augen ist blau.

The color of my eyes is blue. |

The genitive specifies that a quality –the color — “of my eyes” is being discussed. |

| Der Beruf des Mannes ist Arzt.

The profession of the man is doctor. |

The genitive “of the man” indicates whose profession is being discussed. |

| Der Bruder meiner Freundin heißt Lars.

My girlfriend’s brother is named Lars. |

The genitive “of my girlfriend” indicates whose brother is being discussed. |

Note that the genitive construction typically

follows the noun that it modifies (like the English construction using

of). An exception to this is the use of proper names in the genitive, which simply add an –

s or, if the name already ends in

-s, an apostrophe.

Susans Kusine kommt zu Besuch.

Arnold Schwarzeneggars Heimatstadt ist Thal in Österreich.

Hans‘ Auto ist in der Werkstatt.

In colloquial German, genitives denoting possession and relationships are sometimes replaced by

von + the dative:

Die Farbe von meinen Augen ist blau.

Der Beruf von dem Mann ist Arzt.

Der Bruder von meiner Freundin heißt Lars.

Die Kusine von Susan kommt zu Besuch.

In formal standard German, however, the genitive of possession and relationships occurs frequently.

2) Object of a genitive preposition

The object of an accusative preposition takes the genitive case in formal standard German. These are some of the more common genitive prepositions:

| (an)statt |

instead of |

jenseits |

on the other side of |

| anlässlich |

on the occasion of |

kraft |

by virtue of |

| anstelle |

in place of |

laut |

according to |

| aufgrund |

on the basis of |

seitens |

on the part of |

| außerhalb |

outside of |

trotz |

despite, in spite of |

| bezüglich |

with regard to |

während |

during |

| innerhalb |

within |

wegen |

because of |

EXAMPLES OF USAGE:

| Er wohnt außerhalb der Stadt.

He lives outside the city. |

“The city” is the object of the genitive prep.außerhalb. |

| Trotz des Regens spielen wir Fußball.

We’re playing soccer despite the rain. |

“The rain” is the object of the genitive prep. trotz. |

| Aufgrund dieses Fehlers wurde ich entlassen.

I was fired on the basis of this mistake. |

“This mistake” is the object of the genitive prep.aufgrund. |

In colloquial German, some of these prepositions —

wegen,

während,

trotz,

laut — are frequently used with the dative, although this is generally regarded as incorrect in standard formal written German. Note, however, that the genitive and dative forms of feminine nouns are identical.

3) Object of a genitive verb or genitive construction

A number of verbs, adjectives, and idiomatic expressions require a genitive object in German. There used to be many more such genitive expressions in German (as in English

to avail oneself of, to take note of), but these have become replaced over time with other verbs and prepositional phrases. In general, the genitive verbs that are still used convey a highly educated tone.

| sich annehmen |

to see to |

sich enthalten |

to refrain from |

| sich bedienen |

to make use of |

gedenken |

to think of |

| bedürfen |

to be in need of |

sich rühmen |

to boast of |

| sich bemächtigen |

to take control of |

sich vergewissern |

to make certain of |

EXAMPLES OF USAGE:

| Er bedient sich einer Metapher.

He makes use of a metaphor. |

“A metaphor” is the genitive obj. of the verb sich bedienen. |

| Hartholzmöbel bedürfen einer besondern Pflege.

Hard wood furniture is in need of special care. |

“Special care” is the genitive obj. of the verb bedürfen. |

In addition to the genitive verbs, a number of adjectives and other idiomatic phrases are used with genitive objects. Here are some of them:

| bedürftig |

in need |

sicher |

certain |

| bewusst |

conscious |

verdächtig |

suspicious |

| gewiß |

certain |

wert |

worth |

| schuldig |

guilty |

würdig |

worthy |

Notice that the genitive objects that accompany these adjectives are often rendered in English with an accompanying “of”. There is no need to add an additional preposition to the German sentence, since these meanings are included when the noun or pronoun is declined in the genitive case.

EXAMPLES OF USAGE:

| Sie ist des Mordes schuldig.

She is guilty of the murder. |

“(Of) the murder” is the genitive object of the adjective “guilty”. |

| Es ist der Mühe nicht wert.

It is not worth the effort. |

“The effort” is the genitive object of the adjective “worth”. |

| Anna war sich der Gefahr bewusst.

Anna was aware of the danger. |

“(Of) the danger” is the genitive object of the adjective “aware” |

4) Expressions of indefinite time

Expressions of non-specific time that are (1) not adverbs (e.g.,

irgendwann,

manchmal) and (2) not governed by a preposition (e.g.,

seiteiner Ewigkeit) take the genitive case.

EXAMPLES:

| Eines Tages besuchen wir München.

Someday we’ll visit Munich. |

“Someday” is an expression of indefinite time. |

| Eines Abends war ich bei Freunden.

One evening I was at my friends’ place. |

“One evening” is an expression of indefinite time. |

Nouns in the GENITIVE CASE

Finally, here are some examples of nouns in the genitive case. Genitive pronouns are used infrequently and only in elevated speech. Words and endings in

red indicate a change in form from the dative.

| Nouns |

Personal Pronouns |

| masculine |

feminine |

neuter |

plural |

| des Onkels

dieses Onkels

eines Onkels

keines Onkels

unseresOnkels

|

der Tante

dieser Tante

einer Tante

keiner Tante

unserer Tante

|

des Buches

diesesBuches

eines Buches

keinesBuches

unseresBuches |

der Kinder

dieser Kinder

Kinder

keiner Kinder

unsererKinder |

not commonly used in the genitive case |

|

|

[pun:] Geh nicht tief ins Wasser,

weil es da tief ist. |

|

|

|

|

|

The care of one tooth is simple.

But you have a couple more of them. |

|

The Genitive Case in English:

English shows possession through the genitive case, which marks the noun in question with “-‘s” (or in a plural already ending in “-s” with just the apostrophe): “the horse’s mouth”; “the books’ covers.” One can also use a prepositional phrase with “of”: “the color of the car” (= “the car’s color”).

Forming the Genitive in German:

Like the nominative, accusative, and dative cases, the genitive case is marked by pronouns, articles and adjective endings.

In the genitive, there is no distinction between a “der-word” and an “ein-word.”1 As a rule, one-syllable nouns take an “-es” in the masculine or neuter (des Mannes), although colloquial speech will sometime add just -s. Multi-syllabic ones take just “-s”:(des Computers):

| Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| des roten Stuhles |

der neuen Lampe |

des alten Buches |

der roten Stühle |

| roten Stuhles |

neuer Lampe |

alten Buches |

alter Bücher |

Note that the possessive adjectives (mein, dein, sein, ihr, etc.) are not genitive in and of themselves. Nor is the interrogative wessen (= “whose”).

As in the accusative and dative cases, the so-called weak masculine nouns take an “-n” or “-en” in the genitive. For example:

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

der Mensch

den Menschen

dem Menschen

des Menschen

[human] |

der Nachbar

den Nachbarn

dem Nachbarn

des Nachbarn

[neighbor] |

der Herr

den Herrn

dem Herrn

des Herrn

[lord; gentleman] |

der Held

den Helden

dem Helden

des Helden

[hero] |

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

der Bote

den Boten

dem Boten

des Boten

[messenger] |

der Kunde

den Kunden

dem Kunden

des Kunden

[customer] |

der Junge

den Jungen

dem Jungen

des Jungen

[boy] |

der Experte

den Experten

dem Experten

des Experten

[expert] |

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

der Jude

den Juden

dem Juden

des Juden

[Jew] |

der Russe

den Russen

dem Russen

des Russen

[Russian] |

der Kollege

den Kollegen

dem Kollegen

des Kollegen

[colleague] |

der Riese

den Riesen

dem Riesen

des Riesen

[giant] |

Other endings of weak nouns are “-ant,” “-arch,” “-ege,” “-ent,” “-ist,” “-oge,” “-om,” “-oph,” and “-ot.” Some examples:

| der Buddist

[Buddhist] |

der Katholik

[Catholic] |

der Protestant

[Protestant] |

der Pilot

[pilot] |

| der Student

[student] |

der Komödiant

[comedian] |

der Astronom

[astronomer] |

der Patriarch

[patriarch] |

| der Philosoph

[philosopher] |

der Fotograf

[photographer] |

der Enthusiast

[enthusiast] |

der Anthropologe

[anthropologist] |

Again: note that all of these nouns are masculine. Furthermore, their plural forms are the same as their accusative, dative, and genitive singular forms: e.g., den Studenten, dem Studenten, des Studenten; [plural:] die Studenten, den Studenten, der Studenten.(“Herr” is an exception: den Herrn, dem Herrn, des Herrn; [plural:] die Herren, den Herren, der Herren).

Typically, dictionaries identify weak nouns by giving not only the plural but also the weak ending: “der Bauer (-n, -n) farmer, peasant.” The first ending that is cited is that of the genitive case. With weak nouns the accusative and the dative are usually identical with the genitive – but not always. A few weak nouns add “-ns,” for example:

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

der Glaube

den Glauben

dem Glauben

des Glaubens

[belief] |

der Wille

den Willen

dem Willen

des Willens

[will] |

der Gedanke

den Gedanken

dem Gedanken

des Gedankens

[thought] |

der Name

den Namen

dem Namen

des Namens

[name] |

One neuter noun is also weak in the dative and takes an “-ens” in the genitive:

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

das Herz

das Herz

dem Herzen

des Herzens

[heart] |

While the Latin accusative and dative forms of Jesus Christus (Jesum Christum, Jeso Christo) are not used in modern German, the genitive is: Jesu Christi.

The genitive personal pronouns are rare nowadays, but they do exist (some further examples of their use can be found below):

| meiner = (of) me |

unser = (of) us |

| deiner = (of) you |

eurer = (of) y’all |

|

Ihrer = (of) you |

| seiner = (of) him

ihrer = (of) her

seiner = (of) it |

ihrer = (of) them |

The demonstrative pronoun, on the other hand, is commonly employed:

| dessen = (of) him/it (masc.)

derer = (of) her/it (fem.)

dessen = (of) it (neut.) |

derer = (of) them |

| Wir danken im Namen derer, die in Nöte geraten sind. |

We give thanks in the name of those who have come into hardship. |

| Meine Brüder und deren Kinder sind schon angekommen. |

My brothers and their children have already arrived. |

In ambiguous situations, the demonstrative possessive pronoun points to the nearest preceding (i.e. the latter) noun:

| Pauls Sohn und dessen Freunde haben Hunger. |

Paul’s son and (Paul’s) son’s friends are hungry. |

|

[not: Paul’s son and (Paul’s) friends are hungry]. |

When such a pronoun depends on a preceding noun, desselben or derselben can be employed:

| Das Mikroskop, Theorie und Anwendung desselben. |

The Microscope: its Theory and Use [book title] |

|

|

| Die meisten Glaubenslehrer verteidigen ihre Sätze nicht, weil sie von der Wahrheit derselben überzeugt sind, sondern weil sie diese Wahrheit einmal behauptet haben. |

Most doctrinal theologians defend their propositions, not because they are convinced of the truth of them, but because they have at one point asserted that truth. [aphorism by G. C. Lichtenberg] |

Further pronoun examples can be found below.

|

|

|

|

[There is room in this subway car for] 2 bicycles. No bringing [a bike] along when this car is traveling at the front of the train. |

|

Using the Genitive Case in German:

Germans will often assert that the genitive is disappearing from the language. It is certainly used less than one or two centuries ago, but it still occupies an important position. Primarily, the genitive designates a relationship between two nouns in which one of them belongs to the other. The former can be in any case, but the latter is in the genitive:

| Was ist die Telefonnummer deiner schönen Kusine? |

What is your beautiful cousin’s phone number? |

| Sie hat den Brief ihres Vaters gar nicht gesehen. |

She never saw her father’s letter. |

| Das Bild deiner Frau ist besonders gut. |

Your wife’s picture is particularly good. |

| Der Motor dieses Autos ist viel zu klein. |

This car’s engine is much too small. |

| Die größte Liebe aller deutschen Männer ist Fußball. |

The greatest love of all German men is soccer. |

| Das Dach des Hauses war unbeschädigt. |

The roof of the house was undamaged. |

|

|

|

|

Success is the sum of correct decisions |

|

Note that the genitive noun comes second. The opposite sounds either archaic or poetic:

| “Das also war des Pudels Kern!” [Goethes Faust] |

So that was the poodle’s core! |

Proper names in the genitive do precede the noun, however. If the name already ends in “-s” or “-z,” then an apostrophe is added:2

| Was hast du mit Roberts altem Computer gemacht? |

What did you do with Robert’s old computer? |

| Veronikas neuer Freund ist schön. |

Veronika’s new boyfriend is handsome. |

| Heinz’ Hut ist wirklich hässlich. |

Heinz’s hat is really ugly. |

In colloquial speech Germans often use the preposition von (with the dative, of course) instead of the genitive:

| Ist das der Freund von deinem Bruder? |

Is that your brother’s friend? |

| Wir suchen das Haus von seiner Mutter. |

We’re looking for his mother’s house. |

|

|

|

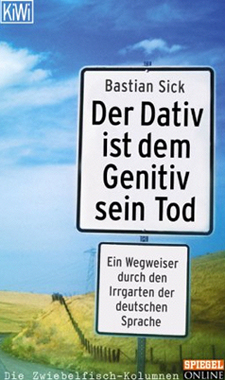

|

The Dative is the Death of the Genitive. A Guide through the Labyrinth of the German Language [book by Bastian Sick] |

|

This construction with “von” is always used if there is no article to mark the genitive:

| Er ist ein Freund von mir. |

He’s a friend of mine. |

| Das Abstellen von Farhrädern ist verboten. |

The parking of bicycles is forbidden. |

Uneducated Germans sometimes use the dative and a possessive adjective to create a genitive effect: Bist du dem Mann seine Frau? Are you the man’s wife?

The genitive is used to indicate an indefinite day or part of the day:

| Eines Tages sollten wir das machen. |

Some day we ought do that. |

| Eines Morgens hat er vergessen, sich die Schuhe anzuziehen. |

One morning he forgot to put his shoes on. |

| Eines Sonntags gehen wir in die Kirche. |

Some Sunday we’ll go to church. |

Although Nacht is feminine, it here – and only here – assumes an analogous structure: Sie isteines Nachts weggelaufen. She ran away one night.

|

|

|

|

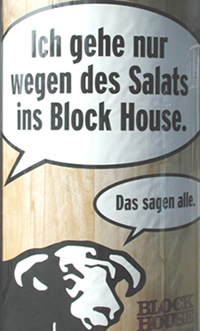

“I go to Block House [a chain of steak houses] only because of the salad.”

“That’s what they all say.” |

|

Prepositions that take the genitive:

A number of prepositions take a genitive object. The most common are statt and anstatt [instead of], trotz [in spite of],wegen [because of] and während [during]. In normal speech, German often use the dative after trotz and wegen.The grammar-police find that appalling, but in fact the dative is actually the older form.

| Statt eines Regenmantels trägt er einen Schirm. |

Instead of a raincoat he carries an umbrella. |

| Trotz der Kälte wollen wir schwimmen gehen. |

Despite the cold we want to go swimming. |

| Wegen der Arbeit meines Vaters mussten wir oft umziehen. |

Because of my father’s work we often had to move. |

| Wir machen alles des Kindes wegen. |

We’re doing everything on account of the child. |

| Während des Sommers wohnt er bei seinen Großeltern. |

During the summer he lives with his grandparents. |

When just a masculine or neuter noun follows the preposition, there is no genitive “-s”:

| Anstatt Fleisch isst sie Tofu. |

Instead of meat she eats tofu. |

Note also:

| Er entschuldigte sich immer wieder wegen seines schlechten Deutsch. |

He apologized repeatedly on account of his bad German. |

| Trotz ihres guten Französisch konnte sie nichts verstehen. |

In spite of her good French she couldn’t understand a thing. |

Less frequently used are außerhalb [outside of], innerhalb [inside of], oberhalb [above], unterhalb [beneath], diesseits [on this side of], and jenseits [on the other side of]:

| Sie wohnen außerhalb der Stadt. |

They live outside the city. |

| Nur ein Spieler darf innerhalb dieses Kreises stehen. |

Only one player is allowed to stand inside this circle. |

| Oberhalb dieser Linie gibt es ein paar Kratzer. |

Above this line there are a couple of scratches. |

| Die Leber sitzt unterhalb der Lunge. |

The liver is beneath the lung. |

| Diesseits der Grenze spricht man Deutsch, aber jenseits spricht man Holländisch. |

On this side of the border German is spoken, but on the other side they speak Dutch. |

|

|

|

|

The grand race of the lowest prices. |

|

George O. Curme’s Grammar of the German Language (New York: Macmillan, 1922) lists a total of 123 prepositions that take the genitive (p. 357), but most are very rare or confined to legal language. They include anlässlich [on the occasion of], angesichts [in the face of; in view of],infolge [as a result of; owing to], ungeachtet [despite; notwithstanding], etc.

Genitive prepositions do not form “da-” compounds. Instead we use genitive demonstrative pronouns, getting structures like während dessen [in the meantime], statt dessen [instead of that], and trotz dessen [despite that] – written as one or two words.

There is a special form of wegen:

| Wir gehen seinetwegen zu Fuß. |

We’re going on foot on account of him (for his sake). |

| Ich mache es ihretwegen. |

I’m doing it on account of her (for her sake). |

| Kaufen Sie das nicht meinetwegen. |

Don’t buy that for my sake. |

| Meinetwegen könnt ihr es verkaufen. |

As far as I’m concerned (for all I care), you can sell it. |

Verbs that take the genitive:

Quite a few verbs once took a genitive object, but over time they have switched to the accusative. One example is vergessen, although the name of the flower Vergissmeinnicht (forget-me-not) remains. Some verbs officially still take the genitive, although many native speakers will use the accusative instead. It is with such formal – some would say stilted – German that you might encounter genitive pronouns:

| Die Angst bemächtigte sich seiner. |

Fear seized him. |

| Wir bedürfen Ihrer Hilfe. |

We require your assistance. |

| Man muss unter 16 sein, um sich eines VCRs zu bedienen. |

You have to be under 16 to operate a VCR. |

| Ich erfreue mich seiner Anwesenheit. |

I enjoy his presence. |

| Wir harren ihrer Ankunft. |

We patiently await her arrival. |

Other genitive constructions:

Some predicate adjectives are also associated with the genitive:

| Er ist seiner Beliebtheit sehr gewiss. |

He’s very certain of his popularity. |

| Ich bin mir dessen bewusst. |

I’m aware of that. |

| Ach ich bin des Treibens müde! [aus Goethes “Wandrers Nachtlied”] |

Oh, I’m weary of this restless activity |

| Sie ist des Mordes schuldig. |

She is guilty of murder. |

| Er ist ihrer nicht wert. |

He’s not worthy of her. |

Certain noun phrases in the genitive act like prepositional phrases:

| Er fährt immer erster Klasse. |

He always travels first class. |

| Sie ist meine Cousine ersten Grades. |

She’s my first cousin. |

| Wir sind heute guter Laune. |

We’re in a good mood today |

| Sie geht guten Mutes nach Hause. |

She goes home in good spirits. |

| Er arbeitet festen Glaubens dafür. |

He works for that with a firm faith. |

| Meines Erachtens ist das nicht nötig. |

In my opinion that’s not necessary. |

| Meines Wissens ist nichts übrig geblieben. |

As far as I know, nothing was left over. |

| Sie behauptet das allen Ernstes. |

She claims that in all seriousness |

| Du bist heute guter Dinge. |

You’re in a cheerful mood today. |

| Wir sind unverrichteter Dinge zurückgekehrt. |

We returned having accomplished nothing. |

|

|

|

|

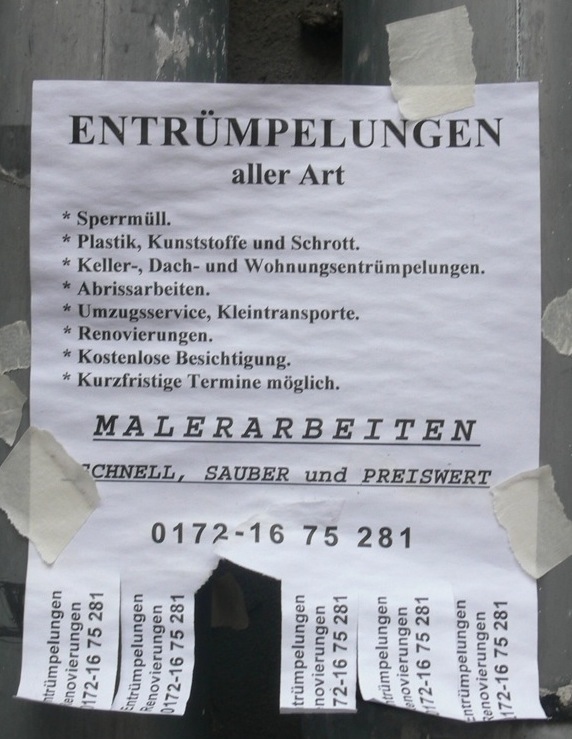

Junk disposal of all kinds

bulky refuse / plastic, synthetics and scrap metal /clearing out of cellars, attics, and apartments /

demolition work / moving service, mini-transport / free inspection / short notice possible

Painting jobs. Fast, clean, and reasonably priced. |

|

1 The “ein-words” are ein, kein, and the possessive pronouns: mein, dein, sein, ihr, unser, euer, Ihr, ihr.

The so-called “der-words” are the articles der, die, das; dies-, jed-, jen-, manch-, solch-, welch-.

Increasingly, Germans are putting apostrophes onto all names, especially in commercial enterprises. This option is unavailable to non-native speakers.

|

|

|

|

Fränky’s Flowers. |

|

]]>