The Differences Between 'Sein' and 'Haben' in German

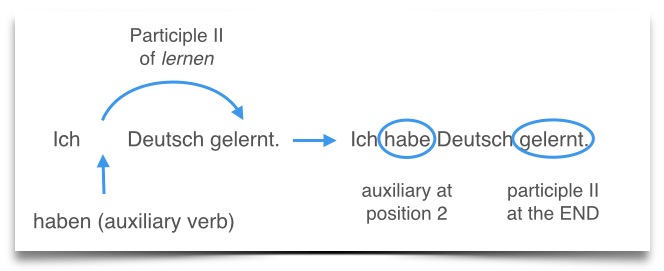

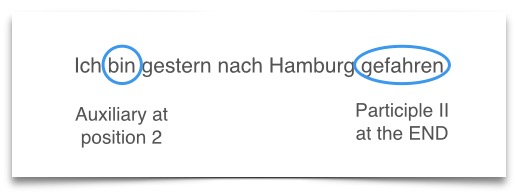

Auxiliary verb (conjugated) + Past Participle (at the end of the sentence)

„Auxiliary verb“ („Hilfsverb“) here means that at position 2 in the main clause (where the conjugated verb is ALWAYS found) there is a verb that helps us to construct the perfect tense in German grammar. The auxiliary verb does not have any meaning by itself, it has only a grammatical function.

Because of this, there are fundamentally only two possible verbs that one can use as the auxiliary verb for constructing the Perfect Tense, namely the verb „haben“ and the verb „sein“. Let me explain to you when to use „haben“ and when to use „sein“.

Firstly, an example:

Present tense: I learn German/ I am learning German. When we want to put this easy sentence into the Perfect tense, the following happens:

What happens?

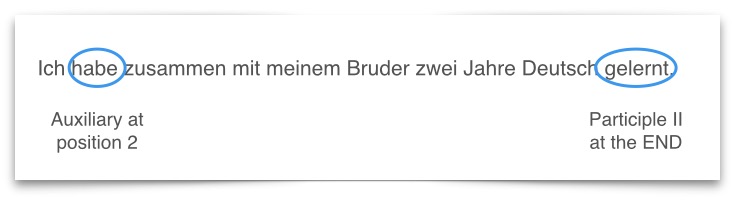

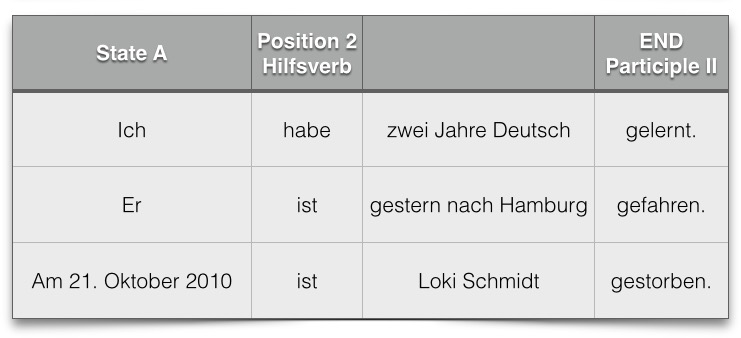

The verb „lernen“ becomes the past participle and moves from position 2 to the END of the sentence. To Position 2 now comes the auxiliary verb „haben“ in conjugated form, so „Ich habE“, with an „e“. This structure always remains the same: auxiliary verb in Position 2, past participle at the end of the sentence, as with much longer sentences:

For you, it is important to note that the actual meaning of the sentence is not shown by the conjugated verb in Position 2 anymore but by the past participle at the end of the sentence. Only the auxiliary verb is ever found in Position 2; mostly we use the auxiliary verb „haben“, and with regular / weak verbs we only EVER use the auxiliary verb „haben“.

When do we use the auxiliary verb „sein“?

The answer to this question is, at first glance, quite simple:Rule:

Verbs about Movement and Change of state use the verb „sein“. And how can we best remember this? Very simple! Be creative and write the verb „sein“ in such a way that you could associate with movement! I am sure, that there are many creative people out there who can do that pretty well. I myself have always thought of this picture here:

And what does this mean exactly?

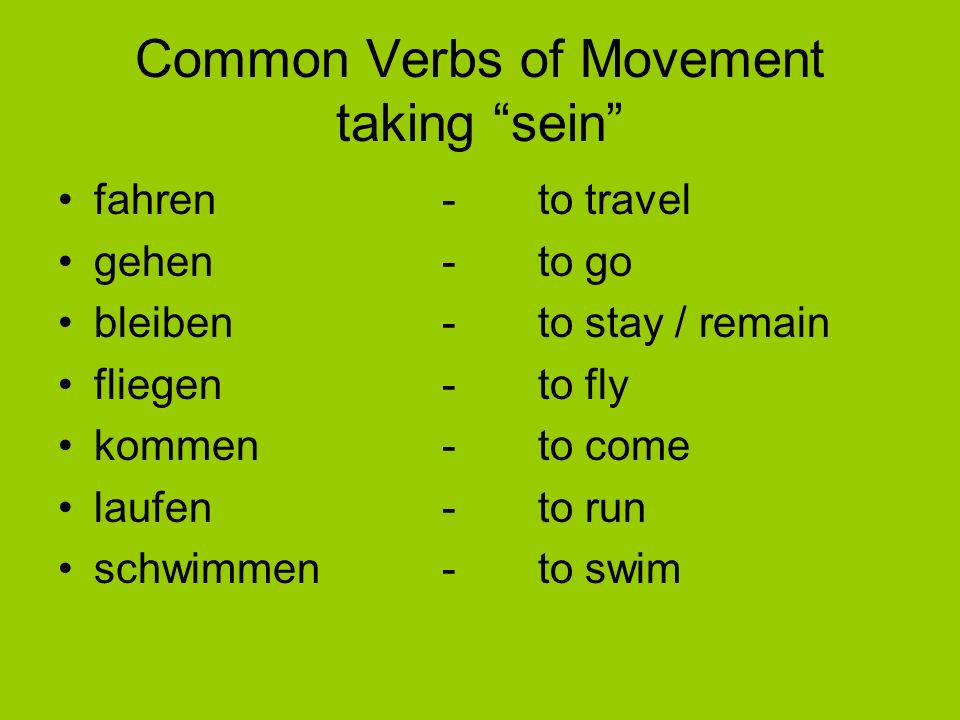

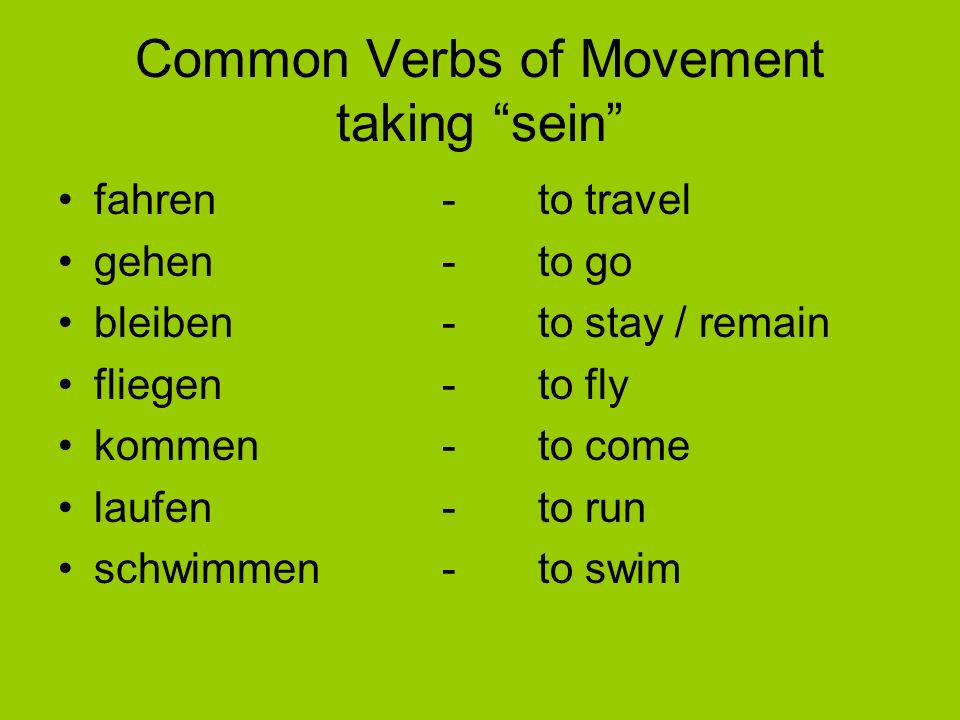

Here are some examples of Verbs of Movement: to go „gehen“, to travel „fahren“, to run „rennen“, to fly „fliegen“ and so on. If we construct the Perfect tense with these verbs, thus we have to use the auxiliary verb „sein“ in conjugated form in Position 2 and, again, the corresponding Past Participle at the END of the sentence:

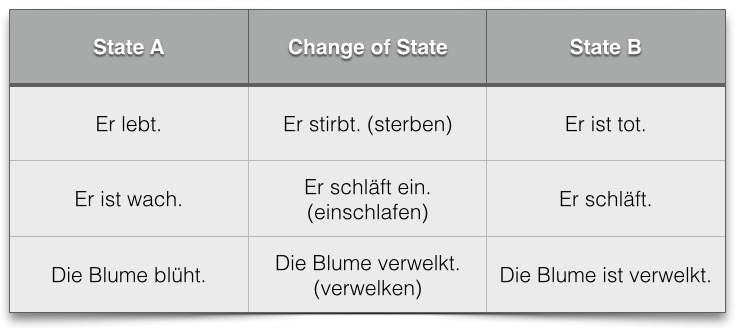

What are Verbs of Change of State?

Verbs of Change of State express when a subject’s state changes from ‚State A‘ to ‚State B‘! Here are a few examples (all sentences in the table are in the present tense):

The verbs „sterben“, „einschlafen“, „verwelken“ and obviously many more are thus so-called Verbs of Change of State and form the Perfect Tense with the auxiliary verb „sein“.

And here once more an overview in the form of a table

So far so good. German students now find it difficult to tell whether they are dealing with verbs of Movement or of Change of State.

Furthermore, there are some verbs that you really can’t say whether they are Verbs of Movement or not, for example with the verb „spielen“. Most people associate that verb with movement, and in spite of this, when constructing the Perfect tense with this verb you use „haben“.

In addition, there are often regional differences. In Austria, some verbs take a different Auxiliary Verb when constructing the Perfect Tense to Germany. So there is always lots for German Students to be confused by!

Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

When do you use the Perfect Tense?

Firstly you must remember, that the Perfect tense conveys the meaning of the past in exactly the same way as the Imperfect tense (Präteritum). There is no difference! It does not matter; both of the following sentences mean exactly the same thing: 65 million years ago, the Dinosaurs died out… Vor 65 Millionen Jahren sind die Dino Saurier ausgestorben. (Perfekt) Vor 65 Millionen Jahren starben die Dino Saurier aus. (Präteritum) The statements made with both grammatical times/tenses mean exactly the same. The difference is only in the communicative context of the sentence. We have to distinguish between a formal, public, literary context and a more easy informal context. Generally the rule is that you use the Imperfect tense in a formal context, for example in literature written in a serious tone such as Newspapers, scientific work or in a serious public speech. If it is meant to be received in a more casual manner, we use the Perfect tense. When we email our friends, for example, or in normal everyday speech and so on. Now you also understand why the Perfect tense is so important in German grammar. If we are talking „ganz normal“ in everyday life and we speak about the past, we use the Perfect tense. So it is very important that you can use it properly.Exceptions

For the verbs „sein“, „haben“ and the Modal verbs (wollen, müssen, können usw.), as a general rule, the Germans do not use the Perfect Tense. You can speculate about why this is – I guess it simply sounds a little awkward or old-fashioned. Because of this, more often we use the Imperfect tense (das Präteritum); with these verbs it is simply easier. Here are a few examples to clarify the difference:sein

Silvester 2001 bin ich in Rom gewesen. (perfect tense) Silvester 2001 war ich in Rom. (past tense)werden

Vor einigen Jahren bin ich Deutschlehrer geworden. (perfect tense) Vor einigen Jahren wurde ich Deutschlehrer. (past tense)bleiben

Gestern bin ich noch ein bisschen länger auf der Party geblieben. (perfect tense) Gestern blieb ich noch ein bisschen länger auf der Party. (past tense)haben

Noch vor einem Jahr hat Paul einen guten Job gehabt. (perfect tense) Noch vor einem Jahr hatte Paul einen guten Job. (past tense)Modal verbs

Als Kind habe ich Pilot werden wollen. (perfect tense) Als Kind wollte ich Pilot werden. (past tense) AUXILIARY VERBS “Haben” OR “Sein” IN THE PRESENT PERFECT TENSE Contrary to English, German sometimes uses a form of “to be” as an auxiliary verb to form the present perfect. In English, it is exclusively “to have” (examples: “I have loved”, “He has kissed”) The only exceptions would come from old nursery rhymes or can be found in the bible on rare occasions. (example “The lord is risen”) The majority of verbs in the present perfect will form via the auxiliary “haben” as well. (examples: “Ich habe geliebt”, “Er hat geküsst” ) However, there are many occasion when you will have to use “sein” instead. The auxiliary “sein” is used if the following two conditions are met and BOTH have to be met. 1. If the verb conveys motion or a change of condition Examples: “Er ist gelaufen”. (He has run), “Sie sind geschwommen” (They have swum), “es ist eingefroren” (It has frozen) “Wir sind gestorben” (we have died).The verbs to “run” and “to swim” express motion, “frieren” and “sterben” are examples of verbs that convey a change of condition. 2. If the verb is intransitive (i.e. it cannot take a direct object) The above verbs are all intransitive. Other examples would include “kommen” or “sein”. “Ich bin gekommen” (I have come) and “Ich bin gewesen” (I have been) A counter example would be “essen”. (Ich habe gegessen.) The word “essen” cries out for a direct object. What have you eaten? The verb is therefore transitive. Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

Both conditions have to be met

Examples:

“Du hast geschlafen” (You have slept) Schlafen is intransitive, but it conveys neither motion nor a change of condition. For this reason “haben” is the auxiliary.“

Ich habe …geöffnet” (I have opened…)The verb “to open” conveys a change of condition and/or motion but the verb is transitive. Hence, the auxiliary is “haben”

If you are like most German language learners, you’ve probably come across the following dilemma when it comes to verbs in the perfect tense: “When do I use the verb haben (to have), when do I use sein (to be)?

This is a tricky question. Even though the usual answer is that most verbs use the auxiliary verb haben in the perfect tense (however watch for common exceptions stated below), sometimes both are used — depending on what part of Germany you’re from.

For instance, northern Germans say Ich habe gesessen, whereas in southern Germany and Austria, they say Ich bin gesessen. The same goes for other common verbs, such as liegen and stehen. Furthermore, the German grammar “bible,” Der Duden, mentions that there is a growing tendency to increasingly use the auxiliary verb sein with action verbs.

However, rest assured. These are other uses of haben and sein to be aware of. In general, keep the following tips and guidelines in mind when deciding between these two auxiliary verbs and you’ll get it right.HABEN PERFECT TENSE

In the perfect tense, use the verb haben:- With transitive verbs, that is verbs that use the accusative. For example: Sie haben das Auto gekauft? (You (formal) bought the car?)

- Sometimes with intransitive verbs, that is verbs that don’t use the accusative. In these cases, it will be when the intransitive verb describes an action or event over a duration of time, as opposed to an action/event that occurs in one moment of time. For example, Mein Vater ist angekommen, or “My father has arrived.” Another example: Die Blume hat geblüht. (The flower bloomed.)

- With reflexive verbs. For example: Er hat sich geduscht. (He took a shower.)

- With reciprocal verbs. For example: Die Verwandten haben sich gezankt. (The relatives argued with each other.)

- When modal verbs are used. For example: Das Kind hat die Tafel Schokolade kaufen wollen. (The child had wanted to buy the chocolate bar.) Please note: You see sentences expressed in this way more in written language.

SEIN PERFECT TENSE

In the perfect tense, you use the verb sein:- With the common verbs sein, bleiben, gehen, reisen and werden. For example: Ich bin schon in Deutschland gewesen. (I’ve already been in Germany.) Meine Mutter ist lange bei uns geblieben. (My mother stayed with us for a long time.) Ich bin heute gegangen. (I went today.) Du bist nach Italien gereist. (You traveled to Italy.) Er ist mehr schüchtern geworden. (He has become shier).

- With action verbs that denote a change of place and not necessarily just movement. For example, compare Wir sind durch den Saal getanzt (we danced throughout the hall) with Wir haben die ganze Nacht im Saal getanzt (we danced the whole night in the hall).

- With intransitive verbs that denote a change in condition or state. For example: Die Blume ist erblüht. (The flower has begun to bloom.)

The Differences Between ‘Sein’ and ‘Haben’ in German

The Differences Between ‘Sein’ and ‘Haben’ in German