IELTS Writing-Transition Words

Transitional Words & Phrases

Using transitional words and phrases in IELTS Writing

Use of Transition words and phrases helps papers read more smoothly, and at the same time allows the reader to flow more smoothly from one point to the next. Transitions enhance logical organization and understandability and improve the connections between thoughts. They indicate relations, whether within a sentence, paragraph, or paper. This list illustrates categories of “relationships” between ideas, followed by words and phrases that can make the connections: Addition: also, again, as well as, besides, coupled with, furthermore, in addition, likewise, moreover, similarlyWhen there is a trusting relationship coupled with positive reinforcement, the partners will be able to overcome difficult situations.

Consequence: accordingly, as a result, consequently, for this reason, for this purpose, hence, otherwise, so then, subsequently, therefore, thus, thereupon, whereforeHighway traffic came to a stop as a result of an accident that morning.

Contrast and Comparison: contrast, by the same token, conversely, instead, likewise, on one hand, on the other hand, on the contrary, rather, similarly, yet, but, however, still, nevertheless, in contrastThe children were very happy. On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, their parents were very proactive in providing good care.

Direction: here, there, over there, beyond, nearly, opposite, under, above, to the left, to the right, in the distanceShe scanned the horizon for any sign though in the distance she could not see the surprise coming her way.

Diversion: by the way, incidentallyHe stumbled upon the nesting pair incidentally found only on this hill.

Emphasis above all, chiefly, with attention to, especially, particularly, singularlyThe Quakers gathered each month with attention to deciding the business of their Meeting.

Exception: aside from, barring, beside, except, excepting, excluding, exclusive of, other than, outside of, saveConsensus was arrived at by all of the members exclusive of those who could not vote.

Exemplifying: chiefly, especially, for instance, in particular, markedly, namely, particularly, including, specifically, such asSome friends and I drove up the beautiful coast chiefly to avoid the heat island of the city.

Generalizing: as a rule, as usual, for the most part, generally, generally speaking, ordinarily, usuallyThere were a few very talented artists in the class, but for the most part the students only wanted to avoid the alternative course.

Illustration:

for example, for instance, for one thing, as an illustration,

illustrated with, as an example, in this case

Illustration:

for example, for instance, for one thing, as an illustration,

illustrated with, as an example, in this case

The chapter provided complex sequences and examples illustrated with a very simple schematic diagram.

Similarity: comparatively, coupled with, correspondingly, identically, likewise, similar, moreover, together withThe research was presented in a very dry style though was coupled with examples that made the audience tear up.

Restatement: in essence, in other words, namely, that is, that is to say, in short, in brief, to put it differentlyIn their advertising business, saying things directly was not the rule. That is to say, they tried to convey the message subtly though with creativity.

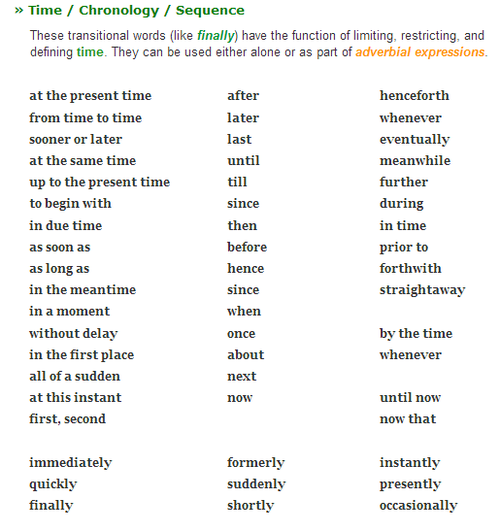

Sequence: at first, first of all, to begin with, in the first place, at the same time, for now, for the time being, the next step, in time, in turn, later on, meanwhile, next, then, soon, the meantime, later, while, earlier, simultaneously, afterward, in conclusion, with this in mind,The music had a very retro sound but at the same time incorporated a complex modern rhythm.

Summarizing: after all, all in all, all things considered, briefly, by and large, in any case, in any event, in brief, in conclusion, on the whole, in short, in summary, in the final analysis, in the long run, on balance, to sum up, to summarize, finallyShe didn’t seem willing to sell the car this week, but in any case I don’t get paid until the end of the month.

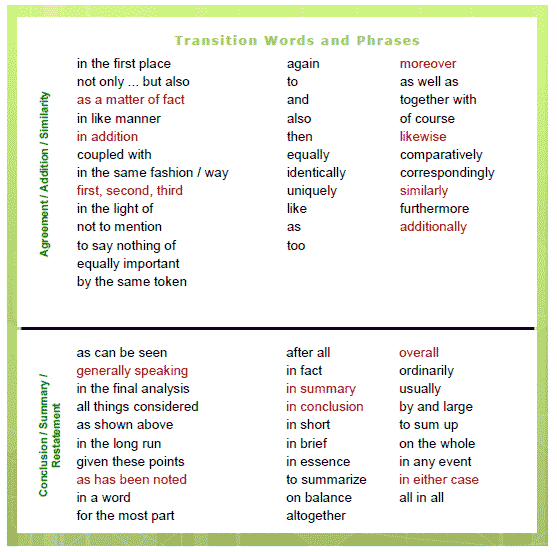

Transition Words and Phrases

This structured list of commonly used English transition words — approximately 200, can be considered as quasi complete. It can be used (by students and teachers alike) to find the right expression. English transition words are essential, since they not only connect ideas, but also can introduce a certain shift, contrast or opposition, emphasis or agreement, purpose, result or conclusion, etc. in the line of argument. The transition words and phrases have been assigned only once to somewhat artificial categories, although some words belong to more than one category.

There is some overlapping with preposition and postposition, but for the purpose of clarity and completeness of this concise guide, I did not differentiate.

Agreement / Addition / Similarity

The transition words like also, in addition, and, likewise, add information, reinforce ideas, and express agreement with preceding material .

.

as a matter of fact

in like manner

in addition

as a matter of fact

in like manner

in addition

coupled with

in the same fashion / way

first, second, third

in the light of

not to mention

coupled with

in the same fashion / way

first, second, third

in the light of

not to mention

to say nothing of

equally important

by the same token

to say nothing of

equally important

by the same token

Opposition / Limitation / Contradiction

Transition phrases like but, rather and or, express that there is evidence to the contrary or point out alternatives, and thus introduce a change the line of reasoning while

albeit

besides

as much as

even though

while

albeit

besides

as much as

even though

List of Transition Words

Usage of Transition Words in Essays

Transition words and phrases are vital devices for essays, papers or other literary compositions. They improve the connections and transitions between sentences and paragraphs. They thus give the text a logical organization and structure (see also: a List of Synonyms). All English transition words and phrases (sometimes also called ‘conjunctive adverbs’) do the same work as coordinating conjunctions: they connect two words, phrases or clauses together and thus the text is easier to read and the coherence is improved. Usage: transition words are used with a special rule for punctuation: a semicolon or a period is used after the first ‘sentence’, and a comma is almost always used to set off the transition word from the second ‘sentence’.Example 1: People use 43 muscles when they frown; however, they use only 28 muscles when they smile.

Example 2: However, transition words can also be placed at the beginning of a new paragraph or sentence – not only to indicate a step forward in the reasoning, but also to relate the new material to the preceding thoughts.

Use a semicolon to connect sentences, only if the group of words on either side of the semicolon is a complete sentence each (both must have a subject and a verb, and could thus stand alone as a complete thought).]]>IELTS Writing-Transition Words Read More »