German Personal Pronouns

Personalpronomen I (Nominativ)

German Personal Pronouns:

A

pronoun in German as well as in English is like a shortcut to refer to a noun, a word that stands for or represents a noun or noun phrase, a pronoun is identified only in the context of the sentence in which it is used. So you must have a prior idea about who “he or she” “er or sie” is. In English we find “I, her, what, that, his”, In German pronouns use is governed by cases (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), number and gender. All these three factors can affect the pronoun.

Types of pronouns include personal pronouns (refer to the persons speaking, the persons spoken to, or the persons or things spoken about), indefinite pronouns, relative (connect parts of sentences), reciprocal or reflexive pronouns (in which the object of a verb is being acted on by verb’s subject), demonstrative, and interrogative pronouns.

The personal (subject) pronouns in German are (ich, du, er, sie, es, wir, ihr, Sie, sie.), and make the equivalent of (I, you, he, she, it, we, you people, you all, they) in English, usually they take the nominative form, since they’re the subject of the sentence. They’re very important and therefore they must be memorized by heart.

I have a pen =

Ich habe einen Kugelschreiber.

| Personal Pronouns in German |

| Singular |

| I |

ich |

| you (familiar) |

du |

| you (formal) |

Sie |

| he, she, it |

er, sie, es |

| Plural |

| we |

wir |

| you (familiar) |

ihr |

| you (formal) |

Sie |

| they |

sie |

German Pronoun

German Personal Pronouns

The personal (subject) pronouns in German are (ich, du, er, sie, es, wir, ihr, Sie, sie.), and make the equivalent of (I, you, he, she, it, we, you people, you all, they) in English, usually they take the nominative form, since they’re the subject of the sentence. They’re very important and therefore they must be memorized by heart.

Present simple (Präsens Indikativ)

| Conjugation |

Meaning |

| ich bin |

I am |

| du bist |

you are |

| er ist

sie ist

es ist |

he is

she is

it is |

| wir sind |

we are |

| ihr seid |

you are |

| sie sind |

they are |

Examples:

Ich bin elf Jahre alt

I am eleven years old

Wie ist dein Name?

What is your name?

Ich bin Frank

I am Frank

Was sind Sie von Beruf?

What’s your profession?

Ich bin Kellnerin

I’m a waitress

Es ist zwei Uhr

It’s two o’clock

Wir sind zufrieden

We are content

Es kann nicht sein

It can’t beMemorizing this German pronoun chart doesn’t help much unless you use it in your own words. The German lessons mentioned above are full of examples of daily use. Here are some examples explaining the usage of above pronouns.

- Ich bin Peter (I am Peter)

- Du bist Peter (You are Peter)

- Sie sind Peter (You are Peter)

- Er ist Peter (He is Peter)

- Sie ist Monika (She is Monika)

- Es ist Tommy (It is Tommy)

- Wir sind Amerikaner (We are American)

- Ihr seid Amerikaner (You are American)

- Sie sind Amerikaner (They are American)

You must have noticed in the above sentences that each German pronoun comes with a different “Be-verb”. Like, “Ich-Bin”, “Du-Bist”, “Er ist”etc. This is very similar to English “I-am”,”You-are” and “He-is” respectively.

A particular German pronoun is always followed by a particular German Be-verb. This is called subject-verb agreement. Subject-verb agreement exist in all languages and German language is no exception.

The following chart shows German pronouns and their possessive form but please learn them through the lessons mentioned above instead of memorizing this chart. This chart is here only for the purpose of providing a summary of possessive form of German pronouns.

German Object Pronouns

Object pronouns replace the object of a sentence;

direct object pronouns take the place of the direct object nouns, let’s take this example “I see

a man”, “a man” can be replaced in English by the direct object pronoun “him” and

not “he”, so it would be “I see

him”, the same thing happens in German:

Ich sehe

einen Mann becomes Ich sehe

ihn.

Note that the direct object pronoun in German is associated with the accusative case:

| Direct Object Pronouns in German |

| Singular |

| me |

mich |

| you (familiar) |

dich |

| you (formal) |

Sie |

| him, her, it |

ihn, sie, es |

| Plural |

| us |

uns |

| you (familiar) |

euch |

| you (formal) |

Sie |

| them |

sie |

The

indirect object pronouns (IOP) are used to replace nouns (people or things) in a sentence to which the action of the verb occurs. In English usually it is preceded by a preposition, “I give the book to Katja”, the name “Katja” is an indirect object noun, to replace it with a pronoun we would say in English “her”, in German we would say “ihr”, note that since the IOP is associated with the

dative, the preposition “to” that we would usually use in English is not used in German, or rather we would say that it’s mixed with the pronoun (look at the table below to understand the concept better), for example “

to her” in German will become one word “

ihr”.

| Indirect Object Pronouns in German |

| Singular |

| to me |

mir |

| to you (familiar) |

dir |

| to you (familiar) |

Ihnen |

| to him, to her, to it |

ihm, ihr, ihm |

| Plural |

| to us |

uns |

| to you (familiar) |

euch |

| to you (formal) |

Ihnen |

| to them |

ihnen |

German Personal Pronouns:

The nominative personal pronouns are one of the first things to learn in German as they are the basics to form our first sentences. One interesting fact about German is that the formal way of writing “you” is “Sie” and it is always capitalized.

| Nominative |

Accusative |

Dative |

Genitive |

| ich |

I |

mich |

me |

mir |

me, to me |

meiner |

mine |

| du |

you |

dich |

you |

dir |

you, to you |

deiner |

yours |

| er |

he |

ihn |

him |

ihm |

him,to him |

seiner |

his |

| sie |

she |

sie |

her |

ihr |

her, to her |

ihrer |

hers |

| es |

it |

es |

it |

ihm |

it, to it |

seiner |

its |

| wir |

we |

uns |

us |

uns |

us, to us |

unser |

ours |

| ihr |

you |

euch |

you |

euch |

you, to you |

euer |

yours |

| sie

Sie |

they

you (formal) |

sie

Sie |

them

you (formal) |

ihnen

Ihnen |

to them

to you (formal) |

ihrer

Ihrer |

theirs

yours (formal) |

| What is a pronoun? A pronoun is – as the word says – to substitute a noun. In a position pro- (for) noun. Have a look. |

|

Singular |

Plural |

| 1. PERSON |

ich |

wir |

| 2. PERSON |

du

Sie (Höflichkeitsform) |

ihr

Sie (Höflichkeitsform) |

| 3. PERSON |

er (maskulin)

sie (feminin)

es (neutrum) |

sie |

Konjugation Präsens I

|

Singular |

Plural |

| 1. PERSON |

ich geh-e |

wir geh-en |

| 2. PERSON |

du geh-st

Sie geh-en |

ihr geh-t

Sie geh-en |

| 3. PERSON |

er geh-t

sie geh-t

es geh-t |

sie geh-en |

Konjugation Präsens II (sein)

|

Singular |

Plural |

| 1. PERSON |

ich bin |

wir sind |

| 2. PERSON |

du bist

Sie sind |

ihr seid

Sie sind |

| 3. PERSON |

er ist

sie ist

es ist |

sie sind |

Konjugation Präsens III (haben)

|

Singular |

Plural |

| 1. PERSON |

ich habe |

wir haben |

| 2. PERSON |

du hast

Sie haben |

ihr habt

Sie haben |

| 3. PERSON |

er hat

sie hat

es hat |

sie haben |

| 4.2 Personal Pronouns in Basic Form (Nominative) |

|

|

What is a pronoun? A pronoun is – as the word says – to substitute a noun. In a position pro- (for) noun. Have a look.

|

Germans drink too much beer.

we can also say

They drink too much beer. |

|

|

ich |

|

I |

|

|

du |

you |

|

|

er |

he |

|

|

sie |

she |

|

|

es |

it |

|

|

wir |

we |

|

|

ihr |

you |

|

|

sie |

they |

|

|

You might have heard before that one of the crazy things in German language is that everything has a gender, even though it might be just a thing. They can be feminine, masculine or neutral. And then there is absolutely no logic in this issue. For instance is the German baby a neutral.

|

Das Kind schläft. = The baby sleeps

Es schläft. = It sleeps. |

|

|

But there are other weird combinations, too.

|

Der Tisch ist braun. (masculine) = The table is brown.

Er ist braun. = He (It) is brown.Das Haus ist grün (neutrum) = The house is green.

Es ist grün. = It is green.Die Tasse ist gelb. (feminine) = The cup is yellow

Sie ist gelb. = She (it) is yellow. |

|

|

Things only get easier in plural forms because there is no difference between the genders of the words.

|

Die Frauen lesen. = The women are reading.

Sie lesen = They are reading.

Die Männer lesen. = The men are reading.

Sie lesen = They are reading.

Die Babys lesen. = The babies are reading.

Sie lesen = They are reading. |

|

|

One big step is to learn the personal pronouns because you will need them a lot.

A conjugation is the change of the verb according to the subject. For this endings (suffixes) are appended to the stem of the verb. First question is What is the stem? Well, it’s the root without the endings. |

| German Conjugation – Weak Verbs |

|

A conjugation is the change of the verb according to the subject. For this endings (suffixes) are appended to the stem of the verb. First question is What is the stem? Well, it’s the root without the endings.

German verbs in basic form always have the ending -en. That means that you take away the -en and you have the stem of the verb. Then you take the right suffix to append it to the verb and you have a perfect conjugation: |

|

infinitive |

bringen |

trinken |

sagen |

kaufen |

|

translation |

to bring |

to drink |

to say |

to buy |

|

stem / root |

bring |

trink |

sag |

kauf |

|

ich |

bring–e (I bring) |

trink-e |

sag-e |

kauf-e |

|

du |

bring–st (you bring) |

trink-st |

sag-st |

kauf-st |

|

er |

bring–t (he brings) |

trink-t |

sag-t |

kauf-t |

|

sie |

bring–t (she brings) |

trink-t |

sag-t |

kauf-t |

|

es |

bring–t (it brings) |

trink-t |

sag-t |

kauf-t |

|

wir |

bring–en (we bring) |

trink-en |

sag-en |

kauf-en |

|

ihr |

bring–t (you bring) |

trink-t |

sag-t |

kauf-t |

|

sie |

bring–en (they bring) |

trink-en |

sag-en |

kauf-en |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

infinitive |

bringen |

weinen |

lachen |

schwimmen |

|

translation |

to bring |

to cry |

to laugh |

to swim |

|

stem / root |

bring |

wein |

lach |

schwimm |

|

ich |

bring–e (I bring) |

wein-e |

lach-e |

schwimm-e |

|

du |

bring–st (you bring) |

wein-st |

lach-st |

schwimm-st |

|

er |

bring–t (he brings) |

wein-t |

lach-t |

schwimm-t |

|

sie |

bring–t (she brings) |

wein-t |

lach-t |

schwimm-t |

|

es |

bring–t (he brings) |

wein-t |

lach-t |

schwimm-t |

|

wir |

bring–en (we bring) |

wein-en |

lach-en |

|

|

Personal pronouns

The nominative personal pronouns are one of the first things to learn in German as they are the basics to form our first sentences. One interesting fact about German is that the formal way of writing “you” is “Sie” and it is always capitalized.

| Nominative |

Accusative |

Dative |

Genitive |

| ich |

I |

mich |

me |

mir |

me, to me |

meiner |

mine |

| du |

you |

dich |

you |

dir |

you, to you |

deiner |

yours |

| er |

he |

ihn |

him |

ihm |

him,to him |

seiner |

his |

| sie |

she |

sie |

her |

ihr |

her, to her |

ihrer |

hers |

| es |

it |

es |

it |

ihm |

it, to it |

seiner |

its |

| wir |

we |

uns |

us |

uns |

us, to us |

unser |

ours |

| ihr |

you |

euch |

you |

euch |

you, to you |

euer |

yours |

| sie

Sie |

they

you (formal) |

sie

Sie |

them

you (formal) |

ihnen

Ihnen |

to them

to you (formal) |

ihrer

Ihrer |

theirs

yours (formal) |

The third person singular is formed with “er” (he), “sie” (she) and “es” (it).

Ich singe ein Lied für dich

I am singing a song for you

Ich habe dir eine Email geschickt

I have sent you an e-mail

The current use of genitive pronouns in German is rare and sounds old (Often, it’s substituted by dative pronouns):

Ich will dir statt seiner einen Kuss geben (old form with genitive)

Ich will dir statt ihm einen Kuss geben (modern form with Dative)

I want to give you a kiss and not him.

Possessive Pronouns

The possessive pronouns in German are:

|

German |

English |

| 1 Person Sing. |

mein |

my |

| 2 Person Sing. |

dein |

your |

| 3 Person Sing. |

sein

ihr

sein |

his

her

its |

| 1 Person Plural |

unser |

our |

| 2 Person Plural |

euer |

your |

| 3 Person Plural |

ihr |

their |

Unfortunately, the possessive pronouns are declined and, this has always been a bit confusing. Let’s try and make this clear. There are 3 declensions depending on the function of the pronoun:

- Attributive (possessive pronoun that comes before a noun) or determiner

- Not attributive without article

- Not attributive with article

Attributive or determiner

This is when the possessive pronoun comes before a noun:

Mein Name ist Helmut

My name is Helmut

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

mein /dein

sein/ihr/sein

unser/euer/ihr |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

mein /dein

sein/ihr/sein

unser/euer/ihr |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

| Accusative |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

mein /dein

sein/ihr/sein

unser/euer/ihr |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

| Dative |

meinem /deinem

seinem/ihrem/seinem

unserem/eurem/ihrem |

meiner /deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/eurer/ihrer |

meinem /deinem

seinem/ihrem/seinem

unserem/eurem/ihrem |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

| Genitive |

meines /deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meiner/deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/eurer/ihrer |

meines/deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meiner /deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/ eurer/ihrer |

Not attributive without article

When the possessive pronoun does not accompany a noun or an article:

Der Kuli ist meiner

The pen is mine

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

meiner /deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/eurer/ihrer |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meines/deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

| Accusative |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meines/deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

| Dative |

meinem /deinem

seinem/ihrem/seinem

unserem/eurem/ihrem |

meiner /deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/eurer/ihrer |

meinem /deinem

seinem/ihrem/seinem

unserem/eurem/ihrem |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

| Genitive |

meines /deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meiner/deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/eurer/ihrer |

meines/deines

seines/ihres/seines

unseres/eures/ihres |

meiner /deiner

seiner/ihrer/seiner

unserer/ eurer/ihrer |

Not attributive with article

When the possessive pronoun is accompanied by an article:

Ein Kuli ist der meine

A pen is mine

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

| Accusative |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meine /deine

seine/ihre/seine

unsere/eure/ihre |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

| Dative |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

| Genitive |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

meinen /deinen

seinen/ihren/seinen

unseren/euren/ihren |

Reflexive pronouns

Just like in English, in some cases, reflexive verbs need a reflexive pronoun to complete the meaning of the verb (Example: I dressed myself)

Ich erinnere mich nicht

I don’t remember

|

Accusative |

Dative |

| 1 Person Sing. |

mich |

mir |

| 2 Person Sing. |

dich |

dir |

| 3 Person Sing. |

sich |

sich |

| 1 Person Plural |

uns |

uns |

| 2 Person Plural |

euch |

euch |

| 2 Person Plural |

sich |

sich |

Demonstrative pronouns

The following demonstrative pronouns exist in German:

- der, die, das (that one)

- dieser (this one)

- jener (that one)

- derjenige (that)

- derselbe (the same one)

These pronouns are declined according to the gender, number and the case of the noun they refer to:

Diese Frau ist Sängerin

This woman is a singer

This picture shows the demonstrative pronouns “der”, “die” and “das”:

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

der |

die |

das |

die |

| Accusative |

den |

die |

das |

die |

| Dative |

dem |

der |

dem |

denen |

| Genitive |

dessen |

deren |

dessen |

deren |

The pronouns “der”, “dieser” and “jener” have a strong declension:

| Strong declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

dieser |

diese |

dieses/dies |

diese |

| Accusative |

diesen |

diese |

dieses/dies |

diese |

| Dative |

diesem |

dieser |

diesem |

diesen |

| Genitive |

dieses |

dieser |

dieses |

dieser |

The pronouns “derjenige”, “derselbe” are both declined “der” with the strong declension and “jenige/selbe” with the weak one:

| Strong declension +

Weak declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

derselbe |

dieselbe |

dasselbe |

dieselben |

| Accusative |

denselben |

dieselbe |

dasselbe |

dieselben |

| Dative |

demselben |

derselben |

demselben |

denselben |

| Genitive |

desselben |

derselben |

desselben |

derselben |

Indefinite Pronouns

The main indefinite pronouns are:

- alle (all)

- andere (other)

- beide (both)

- einige (some)

- ein bisschen (a bit)

- ein paar (a couple)

- jeder (each)

- jemand (someone)

- kein (none)

- man (one)

- mancher (some)

- mehrere (several)

- niemand (no one)

alle

This generally has a strong declension and is almost always used in the plural

| Strong declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

aller |

alle |

alles |

alle |

| Accusative |

allen |

alle |

alles |

alle |

| Dative |

allem |

aller |

allem |

allen |

| Genitive |

alles/allen* |

aller |

alles/allen* |

aller |

Hamburger mit allem

Hamburger with everything

But if it comes before a:

- definite article

- possessive pronoun

- demonstrative pronoun

It is not declined and it is written in its non-changing form

all.

andere

Depending on the particle that comes before it, it has a declension:

- Without article ➜ Strong declension.

Auf dem Tisch steht eine Flasche Wein und eine Flasche mit anderem Inhalt

There’s a bottle of wine on the table and a bottle with other contents

Er lebt jetzt mit anderem Namen in Mexiko

He lives in Mexico now with another name

- Indefinite article or possessive pronouns ➜ Mixed declension.

Mein anderer Hund ist groß

My other dog is big

- Definite article ➜ Weak declension.

Ich habe ein Stück Torte genommen, die anderen hat Michael gegessen

I took a piece of cake. Michael ate the other ones

beide

Usually

“beide” is only used in the plural:

|

Strong declension

(plural) |

Mixed declension

(plural) |

Weak declension

(plural) |

| Nominative |

beide |

beiden |

beiden |

| Accusative |

beide |

beiden |

beiden |

| Dative |

beiden |

beiden |

beiden |

| Genitive |

beider |

beiden |

beiden |

To find out which declension to use, check out the example of

andere.

Wir haben zwei Kinder, und beide sind so unterschiedlich

We have two children, and both are so different

Examples of the 3 declensions:

Beide Arme nach oben

Both arms up (strong)

Meine beiden Arme

Both my arms (mixed)

Die beiden Arme

Both arms (weak)

einige

It only has a strong declension:

Haus mit einigem Luxus

House with (some) luxury

| Strong declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

einiger |

einige |

einiges |

einige |

| Accusative |

einigen |

einige |

einiges |

einige |

| Dative |

einigem |

einiger |

einigem |

einigen |

| Genitive |

einiges |

einiger |

einiges |

einiger |

ein bisschen

It is correct to decline

“ein bisschen” as well as leave it unchanged:

Mit ein bisschen Glück

With a bit of luck

Mit einem bisschen Glück

With a bit of luck

ein paar

“Ein paar” never changes:

Mit ein paar Freunden

With a couple of friends

jeder

Usually, “jeder” only is used in the singular and its declension is strong:

Der Morgen kommt nach jeder Nacht

The morning arrives after every night

| Strong declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

| Nominative |

jeder |

jede |

jedes |

| Accusative |

jeden |

jede |

jedes |

| Dative |

jedem |

jeder |

jedem |

| Genitive |

jedes/jeden* |

jeder |

jedes/jeden* |

jemand

“jemand” is only used in the singular and it doesn’t depend on the gender. It’s correct to decline it as well as to leave it unchanged.

Jemand kommt

Someone’s coming

| Strong declension |

Singular |

| Nominative |

jemand |

| Accusative |

jemand

jemanden |

| Dative |

jemand

jemandem |

| Genitive |

jemands

jemandes |

kein

There are 2 declensions depending on

“kein”‘s function:

- Attributive

- Not attributive without article

Attributive Attributive When the pronoun

“kein” comes before a noun

Ich habe keine Lampe

I don’t have any lamp

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

kein |

keine |

kein |

keine |

| Accusative |

keinen |

keine |

kein |

keine |

| Dative |

keinem |

keiner |

keinem |

keinen |

| Genitive |

keines |

keiner |

keines |

keiner |

Not attributive without article When the pronoun does not accompany a noun

Hast du ein Auto? Nein, ich habe keines

Do you have a car? No, I don’t have one

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

keiner |

keine |

keines |

keine |

| Accusative |

keinen |

keine |

keines |

keine |

| Dative |

keinem |

keiner |

keinem |

keinen |

| Genitive |

keines |

keiner |

keines |

keiner |

man

“man” does not change and it is only used in the nominative to make impersonal phrases.

Man kann nie wissen

You never know

Sentences with the pronoun “man” are an alternative way to form the passive voice.

mancher

“mancher” has a strong declension.

Manche Autos verbrauchen weniger als 3 Liter

Some cars consume less than 3 liters

| Strong

declension |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Nominative |

mancher |

manche |

manches |

manche |

| Accusative |

manchen |

manche |

manches |

manche |

| Dative |

manchem |

mancher |

manchem |

manchen |

| Genitive |

manches /

manchen* |

mancher |

manches /

manchen* |

mancher |

mehrere

“mehrere” is only used in the plural:

In mehreren Sprachen

In several languages

| Strong declension |

Plural |

| Nominative |

mehrere |

| Accusative |

mehrere |

| Dative |

mehreren |

| Genitive |

mehrerer |

niemand

“niemand” is used only in the singular and does not depend on the gender. It’s correct to decline it as well as to leave it unchanged.

Niemand ist schuld

No one is guilty

| Strong declension |

Singular |

| Nominative |

niemand |

| Accusative |

niemand

niemanden |

| Dative |

niemand

niemandem |

| Genitive |

niemands

niemandes |

Forming the masculine and neuter genitive “-en” instead of using “-es”

The indefinite pronouns “alle”, “jeder”, “mancher”, etc (strong declension) form the genitive sometimes with “-en” instead of “-es”.

This has a logical explanation: Most masculine or neuter nouns add an “-s” already when forming the genitive.

Die Meinung manches Lesers

The opinion of some reader

That is why adding “-en” instead of “-es” is the preferred choice in many cases.

Die Meinung manchen Lesers

It is important to emphasize that if the noun does not add an “-s” in the genitive (for example, the nouns with N-declension), the genitive of pronouns is formed only with “-es”.

Die Meinung manches Kunden

The opinion of some client

Personal Pronouns

We can use personal pronouns to replace a previously-introduced noun, speak about ourselves, or address other people. Personal pronouns have to be declined.

|

singular |

plural |

| 1st pers. |

2nd pers. |

3rd person |

1st pers. |

2nd pers. |

3rd pers. |

| nominative |

ich |

du |

er |

sie |

es |

wir |

ihr |

sie |

| dative |

mir |

dir |

ihm |

ihr |

ihm |

uns |

euch |

ihnen |

| accusative |

mich |

dich |

ihn |

sie |

es |

uns |

euch |

sie |

Usage

- Personal pronouns in the 3rd person (er, sie, es) usually replace a previously-introduced noun.

- Example:

- Ich habe eine Katze. Sie ist sehr niedlich.

To avoid misunderstandings, it should always be clear which noun we are replacing (in case of doubt, it’s better to just repeat the noun).

- Example:

- Herr Schneider hatte einen Wellensittich. Er ist gestorben.

(Who – the budgerigar or Herr Schneider?)

- The pronoun can also be used in impersonal forms.

- Example:

- Es regnet. Es ist schon spät.

- The pronoun can also be a placeholder for an entire clause that comes later in the sentence.

- Example:

- Es freut mich, dass du mich besuchst.

(instead of: Dass du mich besuchst, freut mich.)

- We use personal pronouns in the first person (ich, wir) when we’re talking about ourselves.

- Example:

- Ich habe Hunger. Mir ist kalt.

- Wir gehen ins Kino. Uns ist das egal.

- When we address other people, we use the personal pronouns in the 2nd person (du, ihr) or the polite form Sie (identical to the 3rd personal plural, except that the pronoun is written with a capital letter).

- Example:

- Wie heißt du? Wie geht es dir?

- Woher kommt ihr? Welche Musik gefällt euch?

- Können Sie das bitte wiederholen? Kann ich Ihnen helfen?

]]>

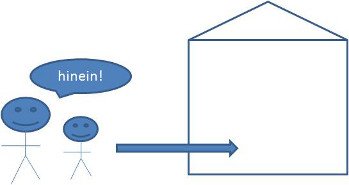

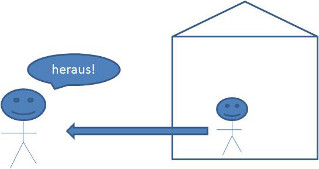

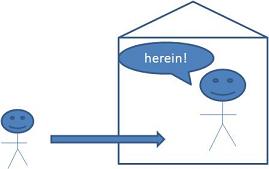

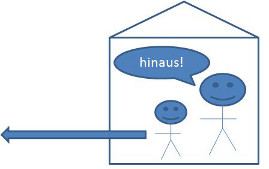

Locative adverbs with the particles “hin” and “her”. The particles “hin” and “her” denote the direction of movement with respect to the person that is speaking. These particles are used often to make adverbs.

Here are some examples so that you understand better:

Locative adverbs with the particles “hin” and “her”. The particles “hin” and “her” denote the direction of movement with respect to the person that is speaking. These particles are used often to make adverbs.

Here are some examples so that you understand better:

German Languages Classes[/caption]

German Languages Classes[/caption]

.jpg) Here are the German ‘definite articles’ – the different ways to say ‘the’ in German – in the ‘nominative case’ with some noun examples:

(You will find a link to German cases at the end of this lesson, but don’t worry too much about ‘cases’ at the moment particularly if you are a complete beginner.)

1.) Masculine German nouns take the definite article: ‘der’.

For example, der Tisch (the table)

2.) Feminine German nouns take the definite article: ‘die’.

For example, die Musik (the music)

3.) Neuter German nouns take the definite article: ‘das’.

For example, das Kind (the child)

Therefore, do not just learn the word for ‘table’ (Tisch) in German, learn its ‘definite article’ as well, for example ‘the table’ (der Tisch).

Need some more examples? Listed below you will find a sample of German nouns listed according to gender. Make sure you learn these useful German nouns together with their respective ‘definite article’.

Here are the German ‘definite articles’ – the different ways to say ‘the’ in German – in the ‘nominative case’ with some noun examples:

(You will find a link to German cases at the end of this lesson, but don’t worry too much about ‘cases’ at the moment particularly if you are a complete beginner.)

1.) Masculine German nouns take the definite article: ‘der’.

For example, der Tisch (the table)

2.) Feminine German nouns take the definite article: ‘die’.

For example, die Musik (the music)

3.) Neuter German nouns take the definite article: ‘das’.

For example, das Kind (the child)

Therefore, do not just learn the word for ‘table’ (Tisch) in German, learn its ‘definite article’ as well, for example ‘the table’ (der Tisch).

Need some more examples? Listed below you will find a sample of German nouns listed according to gender. Make sure you learn these useful German nouns together with their respective ‘definite article’.

German nouns are likely to be…

1.) …masculine and take ‘der’ if:-

– referring to male human beings and the male of an animal species.*

– referring to the days of the week, months, seasons as well as directions.

– the noun ends with ‘ling’.

2.) …feminine and take ‘die’ if:-

– the noun ends with any of the following: ‘ei’, ‘heit’, ‘keit’, ‘ung’, ‘schaft’. For example: die Freundschaft – friendship.

– the noun denotes a female being – and sometimes female animal.

For example: die Frau – the woman.*

3.) …neuter and take ‘das’ if:-

– the noun ends in ‘chen’, ‘lein’, ‘icht’, ‘tum’, ‘ett’, ‘ium’, ‘ment’.

– referring to the names of towns, cities, countries as well as continents.

*Be aware: Many German nouns are classified, however, as being masculine, feminine or neuter even though they are not referring to males, females or inanimate objects. For example: das Mädchen. This means girl in German and takes ‘neuter’, but a girl is clearly a female being. Slightly confusing, I know!

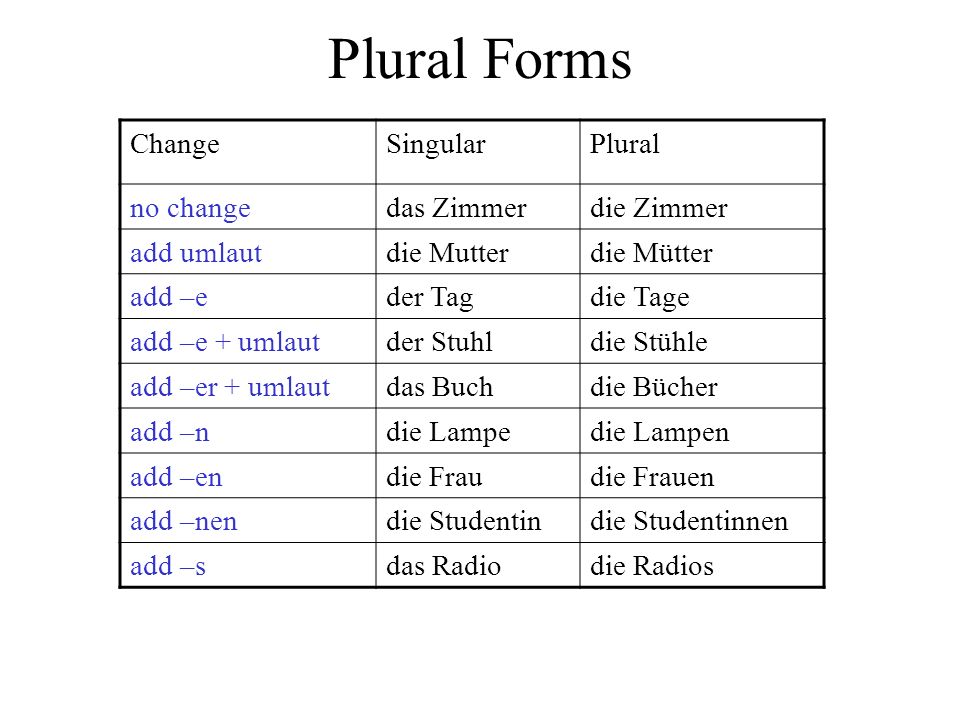

Plural

This lesson so far has focused on nouns and their respective definite articles in the singular form (i.e. one unit: the house), rather than the plural form (i.e. several units: the houses).

The ‘definite article’ for all plural nouns in German is ‘die’. In English, it is of course still ‘the’. Easy to remember, huh?

In English, the noun itself becomes plural in the majority of cases by adding an ‘s’ at the end (houses for example). In German, however, here is where it gets a little more complicated. While a few plural nouns will end in ‘s’ (e.g. die Hotels), the majority form plurals in a variety of different ways.

The only way to be sure of the noun in the plural is to check in a dictionary. (By the way, a really great free online English-German dictionary is

German nouns are likely to be…

1.) …masculine and take ‘der’ if:-

– referring to male human beings and the male of an animal species.*

– referring to the days of the week, months, seasons as well as directions.

– the noun ends with ‘ling’.

2.) …feminine and take ‘die’ if:-

– the noun ends with any of the following: ‘ei’, ‘heit’, ‘keit’, ‘ung’, ‘schaft’. For example: die Freundschaft – friendship.

– the noun denotes a female being – and sometimes female animal.

For example: die Frau – the woman.*

3.) …neuter and take ‘das’ if:-

– the noun ends in ‘chen’, ‘lein’, ‘icht’, ‘tum’, ‘ett’, ‘ium’, ‘ment’.

– referring to the names of towns, cities, countries as well as continents.

*Be aware: Many German nouns are classified, however, as being masculine, feminine or neuter even though they are not referring to males, females or inanimate objects. For example: das Mädchen. This means girl in German and takes ‘neuter’, but a girl is clearly a female being. Slightly confusing, I know!

Plural

This lesson so far has focused on nouns and their respective definite articles in the singular form (i.e. one unit: the house), rather than the plural form (i.e. several units: the houses).

The ‘definite article’ for all plural nouns in German is ‘die’. In English, it is of course still ‘the’. Easy to remember, huh?

In English, the noun itself becomes plural in the majority of cases by adding an ‘s’ at the end (houses for example). In German, however, here is where it gets a little more complicated. While a few plural nouns will end in ‘s’ (e.g. die Hotels), the majority form plurals in a variety of different ways.

The only way to be sure of the noun in the plural is to check in a dictionary. (By the way, a really great free online English-German dictionary is  Other masculine nouns may add an ‘umlaut’ to the vowel in the word. For example: der Mantel, die Mäntel (the coat, the coats) and others will have an additional ‘e’ or umlaut plus an ‘e’. For example: der Weg, die Wege (the path, the paths) and der Busbahnhof, die Busbahnhöfe (the bus station, the bus stations).

Feminine nouns: The majority of feminine plural nouns will end in ‘(e)n’. For example, die Rose, die Rosen (the rose, the roses) and die Zahl, die Zahlen (the number, the numbers). Nouns ending in ‘in’ will have an added ‘nen’ in the plural. For example: die Lehrerin, die Lehrerinnen (the teacher, the teachers – female).

Neuter nouns: Nouns ending in ‘lein’ or ‘chen’ do not change. Once again, only the definite article will indicate if the noun is referring to several girls for example, or just one girl: das Mädchen (singular), die Mädchen (plural).

Other masculine nouns may add an ‘umlaut’ to the vowel in the word. For example: der Mantel, die Mäntel (the coat, the coats) and others will have an additional ‘e’ or umlaut plus an ‘e’. For example: der Weg, die Wege (the path, the paths) and der Busbahnhof, die Busbahnhöfe (the bus station, the bus stations).

Feminine nouns: The majority of feminine plural nouns will end in ‘(e)n’. For example, die Rose, die Rosen (the rose, the roses) and die Zahl, die Zahlen (the number, the numbers). Nouns ending in ‘in’ will have an added ‘nen’ in the plural. For example: die Lehrerin, die Lehrerinnen (the teacher, the teachers – female).

Neuter nouns: Nouns ending in ‘lein’ or ‘chen’ do not change. Once again, only the definite article will indicate if the noun is referring to several girls for example, or just one girl: das Mädchen (singular), die Mädchen (plural).

In a restaurant, you can get service with the following expressions. Just remember to start with Entschuldigen Sie, bitte! (Excuse me, please!)

In a restaurant, you can get service with the following expressions. Just remember to start with Entschuldigen Sie, bitte! (Excuse me, please!)

When you’re walking around town and need directions on the street, the following questions can help you find your way:

When you’re walking around town and need directions on the street, the following questions can help you find your way:

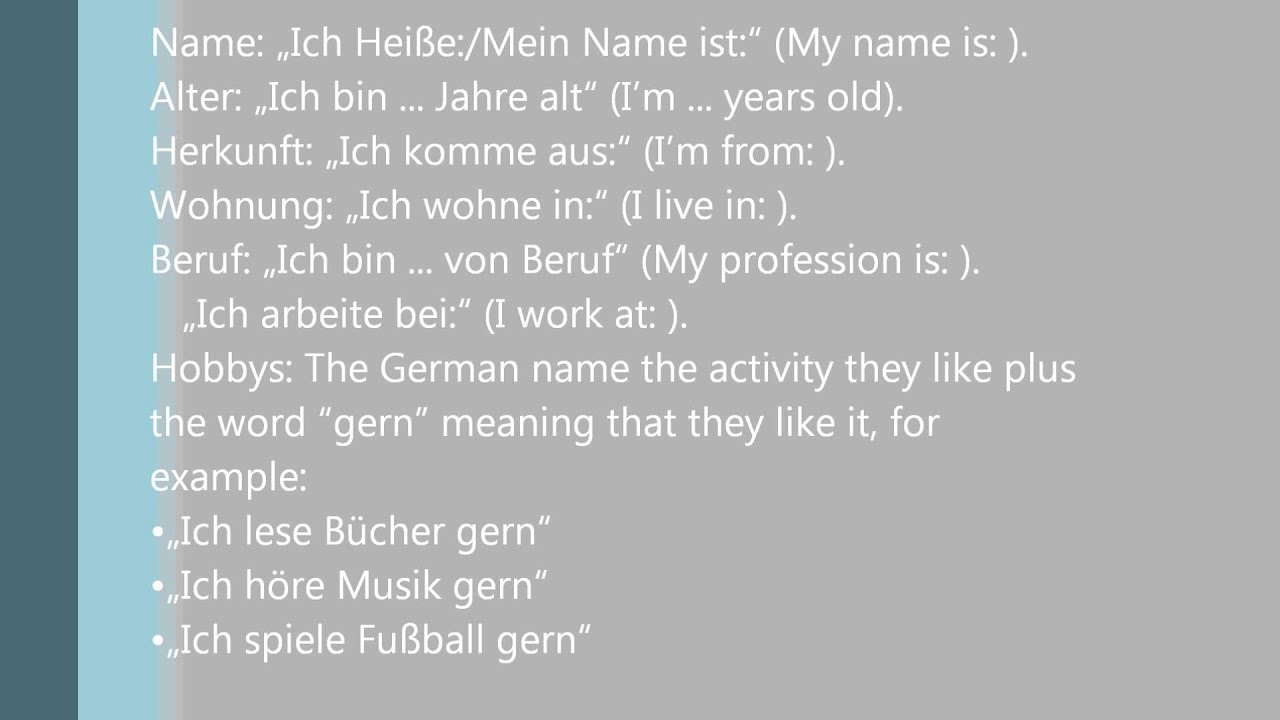

The courses in German Language correspond to the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) . As a result our students are able to compete very well in the Goethe Examinations.

The courses in German Language correspond to the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) . As a result our students are able to compete very well in the Goethe Examinations.

The intensive ” How to Speak German?” Sessions help in sharpening the Grammar and structural skills of the Candidates.

The course materials are designed to constantly refine and fine-tune the skills of the participants and bring out the best in them. Hence, the candidates doing the German courses here shine and outshine others in all walks of life. The knowledge of a new language helps improve their career prospects.

The intensive ” How to Speak German?” Sessions help in sharpening the Grammar and structural skills of the Candidates.

The course materials are designed to constantly refine and fine-tune the skills of the participants and bring out the best in them. Hence, the candidates doing the German courses here shine and outshine others in all walks of life. The knowledge of a new language helps improve their career prospects.

Best Coaching in German[/caption]

Best Coaching in German[/caption]