German Conjunction-adverbs and Coordinate Conjunctions

Conjunction-adverbs in German (Konjunktionaladverbien)

In German, the Konjunktionaladverbien are very interesting. They are adverbs that share properties of conjunctions. This type of word creates a bit of confusion among people trying to learn German. We’ll try and explain this in a way that is understandable:Grammar

The two properties of a Konjunktionaladverb are:- It occupies a position in the clause (like an adverb)

- They associate clauses with one another (like a conjunction)

Die Zimmer sind klein. Trotzdem ist das Hotel für den Preis zu empfehlen The rooms are small. Nevertheless, the hotel is recommended for the price.

Pay attention to the construction: The verb “ist ( sein)” is in the second position. This is because “Trotzdem”, which gives order to the sentence, is behaving like an adverb by occupying the first position in the sentence. Another possibility is to place the Konjunktionaladverb in the middle of the sentence (position 3).Die Zimmer sind klein. Das Hotel ist trotzdem für den Preis zu empfehlen The rooms are small. The hotel, nonetheless, is recommended for the price

List of the most common Konjunktionaladverbien

| Adverbs | Meaning |

|---|---|

| allerdings | however, nonetheless |

| auch | also |

| außerdem | in addition |

| daher | |

| darum | |

| deshalb | therefore, that’s why |

| deswegen | therefore, that’s why |

| doch | so |

| gleichfalls | likewise |

| nur | only |

| so | so |

| somit | hence, therefore |

| sonst | or else |

| zudem | in addition |

| trotzdem | however, nonetheless |

allerdings

It means “however,” “nonetheless,” or simply “but” when it acts as a KonjunktionaladverbIch habe Geschichte studiert, allerdings habe ich keinen Abschluss I studied history but I didn’t finish

Take note that when it is simply acting as an adverb it has another meaning: “of course (as a response)” or “naturally”Ich habe allerdings keine Lust noch länger zu warten Of course I don’t want to wait even longer

auch

It means “also”Ich habe Deutsch studiert. Auch habe ich zwei Jahre mit meiner Familie in Deutschland gewohnt I studied German. I also lived in Germany for two years with my family

außerdem

It means “also”Ich heiße Ana und bin 30 Jahre alt, außerdem bin ich Lehrerin und Mutter von 3 Kindern My name is Ana and I am 30 years old. In addition, I am a professor and mother of three children

daher

It means “therefore” or “that’s why”Ich verstehe leider kein Spanisch. Daher kann ich das Handbuch nicht lesen Unfortunately, I don’t understand Spanish; that’s why I can’t read the manual

darum

It means “therefore” or “that’s why”Wir haben noch keine Erfahrung. Darum ist es für uns wichtig, verschiedene Meinungen zu hören We still don’t have experience. That’s why it is important to us to listen to different opinions

deshalb

deshalb means “therefore” or “that’s why”Mein Mann hat momentan leider keinen Job, deshalb muss ich arbeiten My husband doesn’t have a job at the moment, unfortunately. That’s why I have to work

deswegen

It means “that’s why”Sie hat kein Auto, deswegen fährt sie immer mit der U-Bahn She doesn’t have a car. That’s why she always uses the subway

doch

It means “so” or “but” or “though.” It depends greatly on the context.Wir haben in deiner Wohnung angerufen, doch warst du nicht da We called you at home but you weren’t there

trotzdem

It means “however”Ich bin Deutsche, trotzdem möchte ich das Buch auf Englisch lesen I am German. However, I would like to read the book in English.

| Coordinate conjunctions | Subordinate conjunctions | Compound conjunctions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aber beziehungsweise denn oder sondern und | als bevor bis dass damit nachdem | ob obwohl seit seitdem sobald sofern soweit | sowie während weil wenn wie wo | weder .. noch anstatt..zu entweder…oder sowohl … als (auch) sowohl … wie (auch) je … desto zwar … aber |

Coordinate Conjunctions (Koordinierende Konjunktionen)

The coordinate conjunctions do not modify the position of the verb in the clause. The most common ones are:| Coordinate conjunction | Meaning |

|---|---|

| aber | but |

| beziehungsweise | better put respectively |

| denn | because then |

| oder | or |

| sondern | but but rather |

| und | and |

aber

It means “but”.Die Hose ist schön, aber zu klein The pants are pretty but too small

Er ist klug, aber faul He’s smart but lazy

Das Angebot ist super, aber wir haben keine Zeit The offer is great but we don’t have time

beziehungsweise

It means “better put” or “respectively” and is abbreviated often as bzw.Ein Auto habe ich beziehungsweise meine Frau hat eins I have a car or, better put, my wife has one.

Die Disko ist heute billiger für Frauen und Männer. Es kostet 7 Euro bzw. 10 Euro. The disco is cheaper today for women and men. It costs 7 and 10 Euros, respectively

denn

It means then/because, etc.Ich weinte, denn ich hatte kein Geld I cried because I didn’t have money

Synonymns: weiloder

Means “or”Ich weiß nicht, ob ich lachen oder weinen soll I don’t know whether I should laugh or cry

Wer fängt an, du oder ich? Who starts, you or me?

sondern

Means “but” or “but rather”Das Haus ist nicht alt, sondern neu The house is not old but new

und

It means “and”Meine Freunde und ich wollen ins Kino gehen My friends and I want to go to the cinema

Subordinate Conjunctions

Subordinate conjunctions help to form subordinate clauses. One of the most interesting things about German is that the verb is placed in the last position of the clause in subordinate clauses.| Subordinate conjunction | Meaning |

|---|---|

| als | when |

| bevor | before |

| bis | until |

| dass | that |

| damit | so that |

| nachdem | after |

| ob | whether if |

| obwohl | although |

| seitdem | since |

| sobald | as soon as |

| sofern | provided that as long as |

| soweit | insofar as |

| sowie | as soon as |

| während | while |

| weil | because |

| wenn | if |

| wie | how |

| wo | where |

als

It means “when” if it is a subordinate conjunction. Careful: It’s used only in the past and when the past event only took place one time (temporal conjunction)Als ich Kind war, wohnte ich in München When I was a child, I lived in Munich

“Als” is also used for the construction of the comparative of superiority:Er ist stärker als ich He is stronger than me

bevor

It means “before” (temporal conjunction to show previous action or event)Woran denkst du, bevor du einschläfst? What do you think about before you fall asleep?

bis

It means “until” (temporal conjunction to show subsequent action or event) “Bis” can act as a subordinate conjunction:Warte, bis du gesund bist Wait until you are healthy

or as a preposition:Bis in den Tod until death

dass

It can be translated into English as “that” and is used to start a new subordinate clause.Ich denke, dass die deutsche Sprache kompliziert ist I think that the German language is complicated

dass vs das

Sometimes English speakers confuse “das” (relative pronoun) and “dass” (conjunction). The reason for this is because we use “that” for both words. “das” is used to make relative clauses, which are used to give more information about a noun (Example: the noun “book”):Das ist das Buch, das ich gerade lese This is the book that I am reading

dass is to make common subordinate clauses where more information is given with a verb (Example: the verb to say)Ich habe dir gesagt, dass er heute kommt I told you that he’s coming today

damit

It means “so that” (conjunction of purpose)Ich spare, damit meine Familie einen Mercedes kaufen kann I am saving money so that my family can buy a Mercedes

nachdem

It means “after” (temporal conjunction)Nachdem wir aufgestanden waren, haben wir gepackt After we got up, we packed our bags

ob

It means “whether/if” in the context of indirect questions or to show doubt.Er hat dich gefragt, ob du ins Kino gehen möchtest He asked you if you wanted to go to the cinema

Common mistakes: Confusing the use of ob and wennobwohl

It means “although” or “even though” (concessive conjunction)Ich mag Kinder, obwohl ich keine habe I like kids even though I don’t have any

seit

It means “since” (temporal conjunction). Seit can act as a subordinate conjunction:Ich wohne in Köln, seit ich geboren bin I’ve been living in Cologne since I was born

or as a preposition (seit + Dative):Er wohnt jetzt seit 2 Jahren in diesem Haus He’s been living in this house for two years

seitdem

It means “since” (temporal conjunction)Ich habe keine Heizung, seitdem ich in Spanien wohne I haven’t had heating since I’ve been living in Spain

sobald

It means “as soon as” (temporal conjunction)Ich informiere dich, sobald ich kann I’ll inform you as soon as I can

sofern

It means “as long as” (temporal conjunction)Wir versuchen zu helfen, sofern es möglich ist We will try to help as long as it’s possible

soviel

It means “as much as” or “for all”Soviel ich weiß, ist sie in Berlin geboren For all I know, she was born in Berlin

soweit

It means “as far as”Soweit ich mich erinnern kann, war er Pilot As far as I remember, he was a pilot

sowie

It means “as soon as”Ich schicke dir das Dokument, sowie es fertig ist I’ll send you the document as soon as it’s finished

während

It means “while” or “during” (temporal). While can act as a subordinate conjunction:Während ich studierte, lernte ich auch Deutsch While I was studying, I was also learning German

or as a preposition (während + Genitive):Während meiner Jugendzeit war ich in Basel During my youth I was in Basel

weil

It means “because” (causal conjunction)Sie arbeitet heute nicht, weil sie krank ist She doesn’t work today because she’s sick

Synonyms: dennwenn

It means “if” but only in certain cases. For example: “If you want to go with us, you can.” Expressing doubt would require “ob”. For example: ” I don’t know if you’d like to come with us.” It also means “whenever” (conditional conjunction)Wenn du möchtest, kannst du Deutsch lernen If you want, you can learn German (context of “if” or “in case”)

Wenn ich singe, fühle ich mich viel besser If I sing, I feel much better (context of “whenever I sing…”)

Common mistakes: Confusing the use of “wenn” and “ob”.wie

It means “how” (modal conjunction):Ich weiß nicht, wie ich es auf Deutsch sagen kann I don’t know how to say it in German

or for expressions of equality:Peter ist so dünn wie Tomas Peter is as thin as Tomas

wo

It means “where” (local conjunction)Ich weiß nicht, wo er Deutsch gelernt hat I don’t know where he learned German

Compound Conjunctions

Compound conjunctions are formed by 2 words:| Compound conjunction | Meaning |

|---|---|

| anstatt … zu | instead of [subordinate] |

| entweder … oder | either… or [coordinate] |

| weder noch | neither… nor [coordinate] |

| weder noch | as well as [subordinate] |

| sowohl … als (auch) | as well as [subordinate] |

| sowohl … wie (auch) | as well as [subordinate] |

anstatt…zu

It means “instead of”Ich würde 2 Wochen am Strand liegen, anstatt zu arbeiten I would be lying on the beach for 2 weeks instead of working

entweder…oder

It means “either… or”Entweder bist du Teil der Lösung, oder du bist Teil des Problems Either you’re part of the solution or you’re part of the problem

Die Hose ist entweder schwarz oder rot The pants are either black or red

weder…noch

It means “neither… nor”Weder du noch ich haben eine Lösung Neither you nor I have a solution

sowohl … als (auch)

It means “as well as”Ich habe sowohl schon einen Mercedes als auch einen Audi gehabt I have had a Mercedes as well as an Audi

sowohl … wie (auch)

It means “as well as”Ich habe sowohl ein Auto wie auch ein Motorrad I have a car as well as a motorcycle

]]>German Conjunction-adverbs and Coordinate Conjunctions Read More »

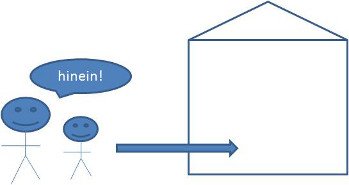

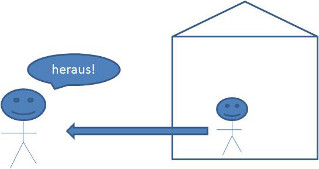

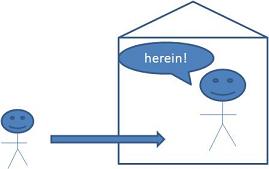

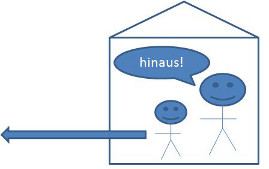

Locative adverbs with the particles “hin” and “her”. The particles “hin” and “her” denote the direction of movement with respect to the person that is speaking. These particles are used often to make adverbs.

Here are some examples so that you understand better:

Locative adverbs with the particles “hin” and “her”. The particles “hin” and “her” denote the direction of movement with respect to the person that is speaking. These particles are used often to make adverbs.

Here are some examples so that you understand better:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

NOTE: Nouns ending with “-in” only are feminine if they refer to a woman.

Examples:

NOTE: Nouns ending with “-in” only are feminine if they refer to a woman.

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Very often

– Plural with “-en”

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Seldom

Examples:

– How often this ending is seen: Seldom

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples:

Examples: