In Spanish, all nouns are either masculine or feminine, whether they denote a person, a thing, a place or an idea.

Masculine nouns usually end in -o: el libro, el curso, el colegio

Compound nouns (verb+noun) are always masculine: el cortaúñas, el rascacielos

Many nouns that end in –ma (those of Greek origin) are masculine: el problema, el tema, el sistema.

Exceptions to the rules include: la mano, la radio, la alarma, la pluma

Feminine nouns usually end in -a: la lengua, la casa, la escuela

Nouns that end in -ción, -sión, or -ía are feminine: la conversación, la televisión, la economía

So are the nouns ending in -dad, -tad, or -tud: la universidad, la amistad, la actitud…

…and those ending in -umbre or -za: la costumbre, la pobreza

Exceptions to the rules include: el día, el mapa, el sofá

Feminine nouns that begin with a stressed a or ha syllable use the masculine article in front of their singular forms, but the feminine article when in plural.

el agua, el aula, el alma, el área, el águila, el hacha, el hada

but

las aguas, las aulas, las almas, las áreas, las águilas, las hachas, las hadas

Some masculine nouns end in a consonant: el señor, el profesor

and they have a corresponding feminine form that ends in -a: la señora, la profesora.

Some nouns have the same masculine and feminine forms. In these cases, the article indicates the gender: el estudiante – la estudiante, el artista – la artista.

Finally, there are nouns that can be both masculine and feminine, but have a different meaning depending on gender.

el frente (front) – la frente (forehead)

el corte (cut) – la corte (court)

el pendiente (earring) – la pendiente (slope)

el cortaúñas

la televisión

la televisión

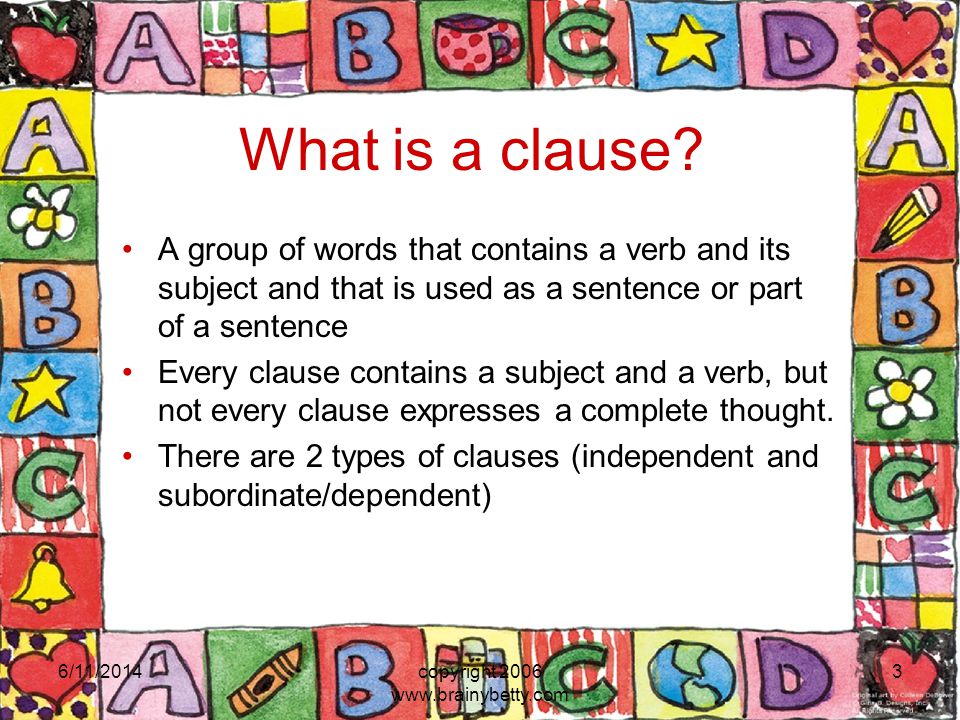

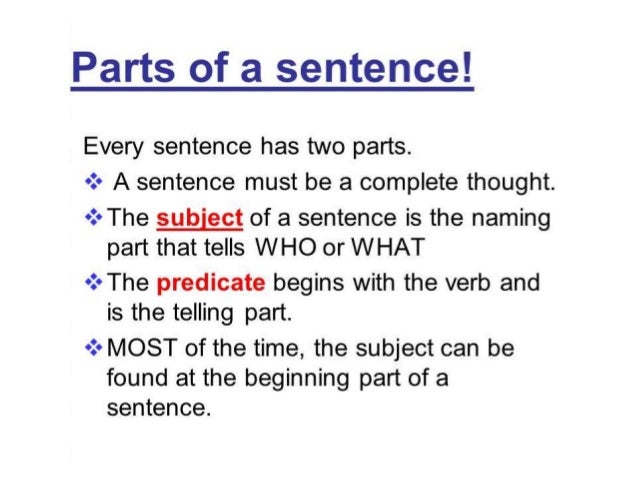

Nouns

Nouns are used to name all sorts of things:

people, animals, objects, places, ideas, emotions, feelings, virtues, defects.

Examples of nouns in English:

cat, dog, house, river, Richard, Santiago, Chile, boy, love, selfishness, courage, loyalty, etc.

Gender

Introduction

In Spanish, all nouns are either masculine or feminine. In most cases we can recognise from the word ending whether a noun is masculine or feminine.

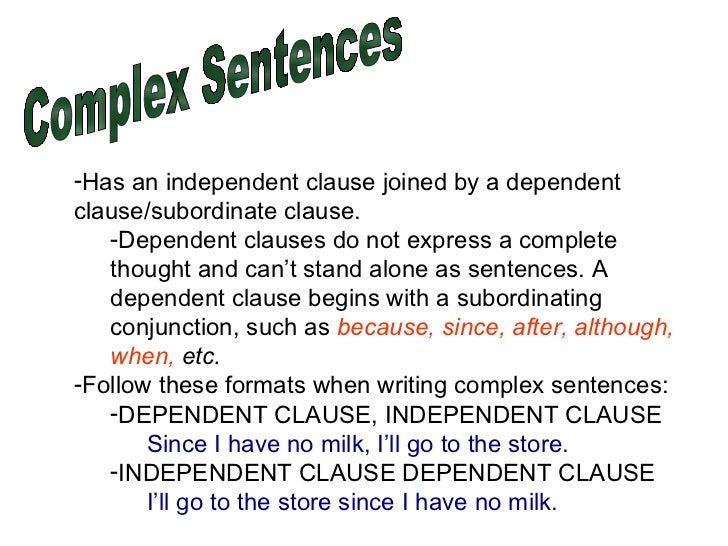

2. Nouns – singular and plural

How to form the plural form of a Spanish noun depends on its ending. There are several different endings:

Nouns ending in a vowel get the ending -s.

perro – perros

escuela – escuelas

Nouns ending in a consonant have the ending -es.

español – españoles

doctor – doctores

Nouns ending in -z have it changed into c when the plural -es is added.

cruz – cruces

voz – voces

Nouns ending in -ión or -és lose the accent when the plural -es is added.

acción – acciones

francés – franceses

In some nouns, mostly compound, only the article changes: el lunes – los lunes, el paraguas – los paraguas, el rascacielos – los rascacielos.

Masculine Nouns

| word feature |

example |

| noun ending with -o |

el trabajo |

| noun ending with -n |

el tren |

| noun ending with -aje |

el viaje |

| noun ending with -r |

el ordenador |

| noun ending with -ón |

el buzón |

| noun ending with -l |

el nivel |

| foreign noun ending with -ma |

el programa |

| male people |

el hombre |

| compass directions |

el norte |

| days of the week |

el lunes |

| months |

el enero |

| numerals |

el uno |

| names of bodies of water and mountains |

el Atlántico |

Feminine Nouns

| word feature |

example |

| noun ending with -a |

la ventana |

| noun ending with -d |

la libertad |

| noun ending with -z |

la cruz |

| noun ending with -ión |

la información |

| female people |

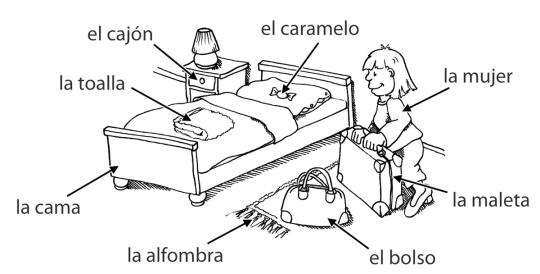

la mujer |

| islands |

Mallorca |

| city names ending with -a |

Barcelona |

| country names ending with -a |

España |

| letters of the alphabet |

la A |

To Note

As with all rules, there are a few exceptions to this one. Therefore it’s best to learn each noun’s gender along with the noun.

In Spanish, nouns may be masculine or feminine. Unlike English, in Spanish even inanimate nouns are classified as masculine or feminine.

You can usually tell whether a noun is masculine or feminine by its ending.

- Nouns ending in ‘s’ are masculine: país, autobús, mes, compas

- Nouns ending in ‘ma’ are masculine: puma, sistema, tema

- Nouns ending in ‘r’, are masculine: motor, par, cráter

- Nouns ending in ‘l’, are masculine: pastel, papel, redil, mantel

- Nouns ending in ‘o’ are masculine: libro, niño, sueño, diccionario

- Nouns ending in ‘n’ are masculine: jabón, jardín, capitán, atún

- About 50% of nouns ending in ‘e’ are masculine: puente, diente, peine

Perhaps ‘SMARLONE’ will help you to remember the above!

- Nouns ending in ‘a’ are feminine: niña, mesa, ventana

- Nouns ending in ‘ción’ are feminine: canción, nación, situación

- Nouns ending in ‘sión’ are feminine: profesión, posesión,

- Nouns ending in ‘d’ are feminine: amistad, ciudad, voluntad

- Nouns ending in ‘z’ are feminine: paz, cruz, luz

- About 50% of nouns ending in ‘e’ are feminine:

- Nouns ending in -ista can be masculine or feminine: turista, dentista, periodista.

- Nouns ending in -ente can be masculine or feminine: gerente, cliente, dirigente.

- Nouns ending in -ante can be masculine or feminine: visitante, agente, dibujante.

Singular and Plural Nouns in Spanish

Most Spanish nouns are either singular (one) or plural (several).

The plural of nouns that end in a vowel (-a, -e, -i, -o, -u) is usually formed by adding an -s.

Examples:

silla/sillas; padre/padres; taxi/taxis; mango/mangos;

Nouns that end in a consonant usually form the plural by adding -es.

Examples:

cartel/carteles; pared/paredes; joven/jóvenes

Exceptions include nouns ending in -s or -x which have the same form in both singular and plural:

Examples:

virus/virus, tórax/tórax, crisis/crisis.

Orthographic rule

When a noun ends in -z, the plural is formed by changing -z to -ces.

el lápiz, los lápices; la raíz, las raíces.

Nouns ending in -í, -ú, -tonics, add -es.

el colibrí, los colibríes; el bambú, los bambúes; el rubí, los rubíes.

In Spanish, all nouns are either masculine or feminine. There several rules which help to identify a given object’s gender; for example, nouns that end in a – like “manzana” (apple) – are almost always feminine, while nouns that end in o – like “bolígrafo” (pen) – are almost always masculine.

To make things even more interesting, each gender has its own set of articles, those little words – the, a, an, some – that essentially introduce a noun and say a little something about it. While in English you can simply apply the same articles – the, a, an, some – to all nouns, in Spanish there are distinctions between masculine and feminine as well as between singular and plural.

Personal pronouns are words used instead of nouns to represent people or things.

Singular

1. yo (I)

2. tú (you)

3. él, ella, usted (he, she, You)

Plural

1. nosotros, nosotras (we)

2. vosotros, vosotras (you)

3. ellos, ellas, ustedes (they, You)

Spanish personal pronouns are similar to those in English, but note that there is no equivalent for the English it form – in Spanish all things are either masculine or feminine (él, ella).

La ciudad es bonita. Ella es bonita.

The city is nice. It is nice.

El coche es nuevo. Él es nuevo.

The car is new. It is new.

The English singular “you” exists in two forms in Spanish: tú (informal) and usted (formal). Similarly, there are two plural forms, vosotros (informal) and ustedes (formal).

Note that these two formal forms – usted, ustedes (and their abbreviated forms, Ud/Vd andUds/Vds) – are followed by the verb conjugated in the 3rd person, not the 2nd.

Veo que tú escribes muy bien en inglés.

I see you write very well in English.

Veo que usted escribe muy bien en ingles.

I see You write very well in English.

The vosotros form is used primarily in Spain. Throughout Latin America, the ustedes form is used to say “you” in both formal and informal contexts, and the verb conjugates as explained above.

¡Vosotros dos siempre llegáis tarde al colegio! (in Spain, talking to children)

¡Ustedes dos siempre llegan tarde al colegio! (in Latin America, talking to children)

You two are always late for school!

Con la tarjeta de fidelidad, ustedes pueden entrar a la zona VIP.(both in Spain and Latin America, talking to clients)

With your membership card, You can access the VIP area.

Definite Articles / Artículos definidos

Definite articles (the) refer to a specific object (

the apple or

the pen). Check out a few examples:

|

Article – English |

Article – Spanish |

Noun – English |

Noun – Spanish |

| masculine, singular |

the |

el |

the pen |

el bolígrafo |

| masculine, plural |

the |

los |

the pens |

los bolígrafos |

| feminine, singular |

the |

la |

the apple |

la manzana |

| feminine, plural |

the |

las |

the apples |

las manzanas |

Indefinite Articles / Artículos indefinidos

Indefinite articles (a, an, some), on the other hand, refer to an unspecified object (

an apple or

a pen ).

|

Article – English |

Article – Spanish |

Noun – English |

Noun – Spanish |

| masculine, singular |

a, an |

un |

a pen |

un bolígrafo |

| masculine, plural |

some |

unos |

some pens |

unos bolígrafos |

| feminine, singular |

a, an |

una |

an apple |

una manzana |

| feminine, plural |

some |

unas |

some apples |

unas manzanas |

Spanish Gender and Articles

In Spanish, unlike English, all nouns (persons, places or things) are either masculine or feminine. The article (‘a’, ‘an’ or ‘the’ in English) must change according to whether the noun that follows is masculine or feminine. It must also agree with the number of the noun – whether it is singular or plural:

| Definite article (‘the’) |

Indefinite article (‘a’ or ‘an’) |

| el |

masculine singular |

un |

masculine singular |

| la |

feminine singular |

una |

feminine singular |

| los |

masculine plural |

unos |

masculine plural |

| las |

feminine plural |

unas |

feminine plural |

Unfortunately, there are no hard and fast rules to tell you which gender a noun should be and most simply need to be learnt.

However, here are some guidelines to show you some common patterns.

Nouns denoting male people and animals are usually but not always masculine:

| el hombre |

the man |

| el toro |

the bull |

| un enfermero |

a (male) nurse |

Nouns denoting female people and animals are usually but not always feminine:

| la niña |

the girl |

| la vaca |

the cow |

| una enfermera |

a (female) nurse |

Some nouns are masculine or feminine depending on the sex of the particular person to whom they refer:

| el/un médico |

the/a (male) doctor |

| la/una médico |

the/a (female) doctor |

| el/un belga |

the/a (male) Belgian |

| la/una belga |

the/a (female) Belgian (NB nationalities are not capitalized in Spanish, but nations are.) |

A noun ending in –ista can be masculine or feminine, depending on whether it refers to a male or female:

| el artista |

the (male) artist |

| la artista |

the (female) artist |

| el pianista |

the (male) pianist |

| la pianista |

the (female) pianist |

Similarly, a noun ending in –nte can be masculine or feminine, depending on whether you are talking about a male or female:

| el estudiante |

the (male) student |

| la estudiante |

the (female) student |

| el presidente |

the (male) president |

| la presidente |

the (female) president |

Some nouns can refer to men or women but have only one gender, whether the person is male or female:

| la/una persona |

the/a person |

| la/una víctima |

the/a victim |

| la/una estrella |

the/a star |

Although you’re likely to be understood by Spanish speakers if you use the wrong genders, there are some instances where it could cause a great deal of confusion. A few nouns change their meaning radically, depending on whether they are masculine or feminine, so they’re well worth learning. Here are some of the more common examples:

| Masculine |

Feminine |

| el capital |

capital (money) |

la capital |

capital (city) |

| un corte |

a cut |

una corte |

a court (royal) |

| un cura |

a priest |

una cura |

a cure (medical) |

| el moral |

the mulberry tree |

la moral |

morals |

| el papa |

the Pope |

la papa |

the potato |

| un policía |

a policeman |

la policía |

the police (force) |

| el radio |

the radius |

la radio |

the radio |

Ser for Specific Things

The verb

ser (to be) has some specific uses that you can learn in order to use it in the context of conversations. The correct usage of this important verb is essential in any language and is not difficult if you learn how to use it.

Naturally, you use the verb by conjugating it in the desired tense and for the appropriate person. For instance, ‘I am’ is

Yo soy (pronounced yio soy). ‘They were’ is

Ellos fueron (pronounced eyios foo-er-ohn). In other words, you must know how to conjugate the verb first. So, please be sure you understand how to conjugate

ser before continuing this lesson.

Expressing liking in Spanish works a bit different than in English. Whereas in English there’s a subject and a direct object of liking, in Spanish there’s an indirect object before gustar to say who likes something.

A mí me gusta esta novela. I like this novel. (Literally: To me is pleasing this novel.)

A Elsa le gustan esos zapatos. Elsa likes those shoes. (Literally: To Elsa are pleasing those shoes.)

If the doer of the action is clear, the first part can be omitted:

A mí me gustan los perros. -> Me gustan los perros. I like dogs.

A nosotros nos gusta ir de compras. -> Nos gusta ir de compras. We like going shopping.

Gusta and gustan are common forms when talking about general likes or dislikes. However, the verb gustar can be used in any and all singular and plural forms as well as in all verb tenses, always keeping in mind that it is defined by the “object of liking”, which is actually the subject of the Spanish sentence.

¿Te gusta el café? Do you like coffee? not ¿Te gustas el café?

Me gustaron sus zapatos. I liked her shoes, not Me gustó sus zapatos.

A mi perro no le gustas (tú). My dog doesn’t like you, not A mi perro no le gusta (tú).

This is because the verb in Spanish is defined by the subject pronoun “you” and not by the indirect object “(to) my dog”, regardless of the word order, so in this case it conjugates as the 2

nd person singular and not 3

rd.

There are a number of other verbs that work the same way in Spanish, e.g.

encantar, faltar, molestar, aburrir, interesar, picar, doler, bastar, quedar.

9. Prepositions de, en, a

These three are some of the most common prepositions in Spanish. However, there is no single meaning for them in English.

DE can mean

of, about, on, from, than, indicating:

- Origin: Soy de Alemania. I’m from Germany.

- Possession: Es el bar de mi tío. It’s my uncle’s bar.

- Cause: Estoy cansada de copiar estas letras. I’m tired of copying these lyrics.

- Composition: Este pañuelo es de seda. This is a silk scarf.

- Comparison: Hay más de 20 personas aquí. There are more than 20 people here.

- Idiomatic expressions: ¿Por qué estáis de pie? Why are you standing?

EN can mean

in, at, on, by, indicating:

- Place: No estamos en casa. We are not at home.

- Time: En otoño hay muy pocos turistas aquí. There are very few tourists here in autumn.

- Travel method: A menudo viajo en avión. I often travel by plane.

- Idioms: ¿Hablas en serio? Are you serious?

A can mean

to, at, for, on, indicating:

- Motion: Quiero ir a Suiza. I want to go to Switzerland.

- Manner: Vine aquí a pie. I came here on foot.

- Time: La clase empieza a las diez. The lesson starts at 10 o’clock.

- Connection between two verbs: Empecé a hacer yoga. I started doing yoga.

- Before an indirect object: Di tus apuntes a Ana. I gave your notes to Ana.

- Before a person as a direct object – personal “a”: ¿Conoces a Martin? Do you know Martin?

Saying Your Name

If you wish to tell what your name is, you must use the verb

ser. Below is an example of this use:

- Yo soy Patricia y ella es Carol. (I am Patricia and she is Carol)

Note that, in Spanish, you can also say

me llamo (I call myself, pronounced: meh yiah-moh) followed by your name to mean ‘My name is. . .’

Relationships

When expressing the relationship that ties a person with another, whether because of work, family ties, or legal ties, one must use

ser. Below is an example of this use:

- John es mi jefe. (John is my boss)

- Nosotros somos hermanos. (We are brothers)

- Lauren es mi suegra. (Lauren is my mother in law)

Describing Physical Aspects

The verb

ser is always used with the use of adjectives that serve to describe physical characteristics of a person, object, or animal. Below are some examples for each case:

- Erika es alta y delgada. (Erika is tall and thin)

- La mesa es nueva. (The table is new)

- Mi perro es grande. (My dog is big)

Colors are also a physical characteristic. When referring to colors, always use

ser. Below is an example:

- Mi coche es rojo. (My car is red)

Describing Personality & Intellectual Features

The use of adjectives that serve to describe personality or intellectual features is also always uses the verb

ser, as in the examples below:

- Pedro es inteligente. (Pedro is intelligent)

- Mi gato es muy independiente. (My cat is very independent)

Place of Origin & Nationality

When expressing your place of origin, you use

ser. The same happens for nationality. Below are two examples:

- Mi amiga es de Colombia. (My friend is from Colombia)

- Ella es colombiana. (She is Colombian)

Profession & Occupation

The profession you have, but also the word that describes the type of worker you are (your occupation), is always used with

ser as follows:

- Carlos es arquitecto. (Carlos in an architect)

- Mario es mesero. (Mario is a waiter).

For the English word “for”, there are two Spanish words, por and para. In order to understand which one to use, you must think of their meaning and use in a sentence. Generally speaking,para indicates purpose or intention (¿Para qué? For what purpose?), whereas por expresses motivation or substitution (¿Por qué? For what reason?).

Uses of PARA:

- Destination: Mañana salgo para Helsinki. I’m leaving for Helsinki tomorrow.

- Intended use: Este regalo es para ti. This present is for you.

- Deadline: Tiene que estar listo para el lunes.I need it ready by Monday.

- Purpose: Fui a Irlanda para mejorar mi inglés. I went to Ireland in order to improve my English.

- Contrasting: Para ser extranjera, hablas muy bien el finés. For a foreigner, you speak Finnish very well.

- Opinion: Para mí, mirar la tele es una pérdida de tiempo.To me, watching TV is a waste of time.

- Actions soon to be completed: Está para salir. He’s about to leave.

Uses of POR:

- Reason: Cerramos la ventana por la lluvia. We closed the window because of the rain.

- Movement through space: Un globo entró por la ventana. A balloon came in through the window.

- Duration of time: Trabajé en Argentina por 2 meses. I have worked in Argentina for 2 months.

- Exchange: Te doy 500 dólares por esta moto. I’ll give you 500 dollars for this motorcycle.

- On behalf of/In favour of: Lo hago por ti. I’m doing this for you.

- Agent in passive phrases: Esta zona no fue afectada por la sequia. This area wasn’t affected by drought.

- Idiomatic expressions, such as: por fin – finally, por supuesto – of course, por lo tanto– therefore, etc.

Note the difference in meaning between the following examples:

Lo compré por ella. I bought it because of her (because she wanted me to).

Lo compré para ella. I bought it for her (in order to give it to her).

The Verb Estar

Estar is one of two verbs in Spanish meaning ‘to be.’ When we use the verb

estar, we have to conjugate, or change, the verb to match the subject of the sentence. In Spanish, verbs have different conjugations, or forms, for each subject pronoun, like I, you, he or she. To make these different forms, you change the letters at the end of the verb infinitive. We will change the letters ‘ar’ at the end of

estar to different endings to indicate who is doing the action and the time of the action – present or past. This lesson will look at three different ways to conjugate the verb

estar: the

present indicative,

imperfect, and

present subjunctive.

Present Indicative

In the present indicative, we use the verb

estar to describe temporary feelings, such as happiness or sadness, and locations of things. In fact, there’s an easy rhyme that helps you remember when to use

estar – ‘How you feel and where you are, always use the verb

estar.’

Estar is an irregular verb in the present indicative tense. This means that it doesn’t follow conjugation rules, so you’ll need to memorize the different forms. Also, you usually will not say a separate word for the subject when you use

estar because there is a different form of the verb for each subject pronoun. In the chart you can see how the form of the verb is different for each subject pronoun.

| Present indicative form of estar |

Pronunciation |

Meaning |

| Estoy |

ay-stohy |

I am |

| Estás |

ay-stahs |

you are (singular informal) |

| Está |

ay-stah |

he is / she is / you are (singular formal) |

| Estamos |

ay-stah-mohs |

we are |

| Estáis |

ay-stah-eest |

you are (plural informal) |

| Están |

ay-stahn |

they are / you are (plural formal) |

Did you notice that some subject pronouns share the same form of

estar? Like

está and

están? For

está you can add the subject pronoun – either

él (he),

ella (she) or

usted (you – singular, formal) – before the verb. This would make it clear to everyone who the subject of the verb is.

Están follows a similar pattern. You can add

ellos (they – masculine or mixed gender),

ellas (they – female), or

ustedes (you – plural, formal) before the verb. Adding the subject pronoun before these two forms will make the meaning of your message clear and easy for everyone to understand.

Imperfect

Verbs that are in the imperfect tense always describe the past. They can describe repeated actions in the past, like habits. Any time that you say that you ‘used to’ do something, you want to use the imperfect tense. You also use imperfect verbs to describe mental activities in the past, like thinking or to describe the scene, location or environment where something in the past happened.

For the imperfect tense, you use the forms of

estar that you see in the chart. Like we saw with the present indicative, some subject pronouns share the same forms of

estar. When you have the same form of estar for more than one subject pronoun, you’ll want to make it clear what the subject is. You can do this by putting the subject pronoun before the form of

estar in the sentence. So, if you have the sentence

Estaba triste ( _____ was sad), it isn’t clear who was sad. You can make it clear by adding the subject pronoun before

estaba, such as

Él estaba triste. (He was sad.)

Common Spanish Verbs Ending in -er

Using -Er Verbs in Present Tense Spanish

Verbs are action words that change slightly depending on who is doing the action. In Spanish, the last two letters of an

infinitive verb, or non-conjugated verb, tell us which ending to replace the

-er with to match the

subject of the verb, or the person/people doing the action.

Here are the subjects in Spanish:

- yo: I

- tú (pronounced: too): you (informal)

- usted: you (formal)

- él: he

- ella (pronounced: A-yah): she

- nosotros/nosotras: we

- vosotros/vosotras: you all (informal, in Spain only)

- ustedes: you all

- ellos/ellas(pronounced: Ayohs/A-yahs): they

Conjugating -er Verbs in Spanish

Once you choose the correct subject, you can match it to the correct ending of the –

er verb. We take off the

-erand replace it with the right ending for the subject of the sentence.

| yo: -o |

tú: -es |

usted, él, ella: -e |

nosotros/as: -emos |

vosotros/as: -‘eis |

ustedes, ellos, ellas: -en |

These endings can be inserted into many regular –

er verbs you come across in Spanish. There are other verbs in Spanish that end with –

ar and –

ir, which have different sets of endings. The

yo form of –

ar, –

er and –

ir verbs are all

-o.

Often in Spanish, you might see sentences without the subject written in front of the verb. That’s because the different verb endings make it clear who the subject is without restating it. For example, in the present tense, when you see a conjugated verb that ends in

-o, you’ll know that the subject is

yo, or

I, even if it isn’t stated.

Common -er Verbs

Here’s a list of some common –

er verbs:

| aprender |

to learn |

| beber |

to drink |

| comer |

to eat |

| comprender |

to understand; to comprehend |

| correr |

to run |

| creer (en) |

to believe (in) |

| leer |

to read |

| proteger (pronounced: pro-teh-hair) |

to protect |

| responder |

to respond |

| vender |

to sell |

Let’s practice!

Let’s start with

comer. I love to eat hamburgers for lunch. I might say

Yo como hamburguesas mucho. (I eat hamburgers a lot.) Your sister prefers soup, so you could explain that

Ella come sopa. (She eats soup.)

Now let’s try

beber. Marisa and I are drinking water, so we will say

Nosotras bebemos agua. We use the feminine form of

we, or

nosotras, since Marisa is a girl.

Your mother and father drink coffee, so that is

Ellos beben café. (They drink coffee.)

You can use this same process to conjugate any regular –

er verb.

Creer, Leer

The verbs

creer and

leer look a little different since there are two vowels in the middle of the infinitive verb. To conjugate

leer and

creer, remove the second ‘e’ to add the correct endings.

Yo leo el periódico. (I read the newspaper.)

Tú lees el libro. (You read the book.)

Usted cree en la astrología. (You (formal) believe in astrology.)

Martín y Javier creen en Dios. (Martín and Javier believe in God.)

Proteger

There’s one more thing to keep in mind for the verb

‘proteger. For pronunciation reasons, we need to change the

g to a

j in the

yo, or

I form. ‘I protect my house’ is

Yo protejo a mi casa. The other forms of

proteger keep the ‘g’:

Ustedes protegen a los niños. (You all protect the children.)

Nosotras protegemos la comida. (We (all female) protect the food.)

Tener: Definition & Conjugation

Tener

The verb

tener in Spanish means ‘to have’.

Tener is also used to form many common expressions that we use with ‘to be’ in English.

Conjugating Tener in the Present Tense

Tener is an

irregular verb, which means that its conjugations don’t follow a common pattern. Since we use this verb a lot in Spanish, it’s a good idea to practice the present tense conjugations so you can use them quickly.

| yo tengo |

I have |

|

nosotros/as tenemos |

we have |

| tú tienes |

you (informal) have |

|

vosotros/as tenéis |

you all (informal; Spain only) have |

| usted/él/ella tiene |

you (formal)/he/she has |

|

ustedes/ellos/ellas tienen |

you all/they have |

You can create sentences by starting with the subject and then using the matching verb form. Since each verb form has different spellings, we can also omit the subject when it’s pretty clear who is doing the action or who has the item.

Let’s say I have a car. I can say

Yo tengo un carro. Since the

tengo form of

tener can only be used for

yo (I), you can leave that word out and say simply

Tengo un carro.

Now that you know how to conjugate

tener, let’s use it to form common expressions in Spanish.

| tener __ años |

to be __ years old |

| tener hambre |

to be hungry |

| tener sed |

to be thirsty |

| tener cuidado |

to be careful |

| tener razón |

to be correct; to be right |

| tener sueño |

to be sleepy |

| tener que |

to have to |

| tener ganas (de) |

to feel like |

| tener frío |

to be cold |

| tener calor |

to be hot |

| tener prisa |

to be in a hurry |

For each of these expressions, we’ll use the same forms of

tener that we practiced above.

Let’s say that Marta is hungry and her brother Jorge is sleepy. We can say:

Marta tiene hambre y Jorge tiene sueño. I am thirsty, so I’ll say

yo tengo sed, or simply

tengo sed.

If we say that two plus two is four, we are right, or

tenemos razón.

If Javier and Luisa say that two plus two is five, they are not right;

ellos no tienen razón.

Tener in the Preterite Tense

Tener is irregular in the past

preterite tense also. You may have learned about the preterite tense in Spanish before. We use this form of the verb to talk about a series of events in the past and to talk about things with a clear beginning and end.

Spanish Pronouns

Subject Pronouns in Spanish

The subject pronouns in Spanish are:

|

Singular |

Plural |

| 1st Person |

yo |

nosotros, nosotras |

| 2nd Person |

tú, usted |

vosotros, vosotras, ustedes |

| 3rd Person |

él, ella |

ellos, ellas |

1st Person = the person who is speaking

2nd Person = the person you are speaking to or listening to

3rd Person = the person you are talking about

An explanation of what each Personal Pronoun is:

| Personal

Pronoun |

|

Situation |

| Yo |

I |

= it refers to yourself |

| Tú |

You |

= the person you are speaking to – informal (family or friend) |

| Vos |

You |

= you in Argentina |

| Usted |

You |

= the person you are speaking to – formal (respect, older people) |

| Él |

He |

= man or boy (another person) |

| Ella |

She |

= woman or girl (another person) |

| Nosotros * |

We |

= tú + yo OR Usted + yo |

| Nosotras * |

We (fem) |

= tú + yo OR Usted + yo (both are women / girls) |

| Vosotros |

You |

= tú + tú (this is not used much in Latin America) |

| Vosotras |

You (fem) |

= tú + tú (only women – this is not used much in Latin America) |

| Ellos ** |

They |

= él + él OR él + ella |

| Ellas ** |

They (fem) |

= ella + ella (only women or girls) |

| Ustedes |

You |

= Usted + Usted (= tú + tú in Latin America) |

* Nosotros vs Nosotras

There are two ways of saying “We” in Spanish depending on who is speaking or in the “group”.

If there is at least one man (or boy) in the “group” of people, then “We” will be

Nosotros in Spanish.

If there are only women (or girls) in the group, and no men, then “We” will be

Nosotras in Spanish.

You (man) + Man = Nosotros (= yo + él)

You (man) + Woman = Nosotros (= yo + ella)

You (woman) + Man = Nosotros (= yo + él)

You (woman) + Woman =

Nosotras (= yo + ella)

** Ellos vs Ellas

The same applies to “They” (ellos or ellos). If there is one or more men in the group, then it will be

ellos.

If everyone in the group is female, then you would use

ellas.

Subject Pronouns in Spanish – Summary Charts

Subject Pronouns

Every sentence has a subject. The subject of the sentence is who or what is doing the action in the sentence or is being described.

In English, the subject pronouns are I, you, he/she/it, we, they.

In Spanish there are several other forms of these subject pronouns. As with many other grammatical forms, there are different gender forms of pronouns.

| English Subject Singular Pronoun |

Spanish Subject Singular Pronoun |

English Subject Plural Pronoun |

Spanish Subject Plural Pronoun |

| I |

yo |

We |

nosotros (masculine or mixed gender group)

nosotras (feminine) |

| you |

tú (familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

ustede (formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

you (as in all of you) |

ustedes (used in Latin American countries for both formal and informal, used in Spain for formal)

vosotros (informal masculine and mixed gender groups -used in Spain)

vosotras (informal feminine – used in Spain) |

| he

she |

él

ella |

they |

ellos (masculine or mixed gender group)

ellas (feminine group) |

Direct Object of Preposition Pronouns

| English Direct Object of Preposition Singular Pronoun |

Spanish Direct Object of Preposition Singular Pronoun |

English Direct Object of Preposition Plural Pronoun |

Spanish Direct Object of Preposition Plural Pronoun |

| I |

mí |

We |

nosotros (masculine or mixed gender group)

nosotras (feminine) |

| you |

ti (familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

usted (formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

you (as in all of you) |

ustedes (used in Latin American countries for both formal and informal, used in Spain for formal)

vosotros (informal masculine and mixed gender groups -used in Spain)

vosotras (informal feminine – used in Spain) |

| he

she |

él

ella |

they |

ellos (masculine or mixed gender group)

ellas (feminine group) |

- If the pronoun “mi” is used with the preposition “con” the word conmigo is used instead.

- If the pronoun “ti” is used with the preposition “con” the word contigo is used instead.

- If the pronoun in the preposition refers back to the subject of the sentence, use the word consigo – otherwise use the regular prepositional pronouns.

There are several prepositions that use the subject pronouns rather than the prepositional pronouns with prepositions. They are:

- entre – between

- excepto – except

- incluso – including

- menos – except

- según – according to

- salvo – except

Direct Object Pronouns

The object that directly gets or receives the action of the verb is called the direct object. If that direct object noun is replaced by a pronoun, it is a direct object pronoun.

| English Direct Object Singular Pronoun |

Spanish Direct Object Singular Pronoun |

English Direct Object Plural Pronoun |

Spanish Direct Object Plural Pronoun |

| me |

me |

us |

nos |

| you |

te (familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

lo, la(formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

you (as in all of you) |

os (informal)

los, las (formal masculine and mixed gender groups -used in Spain) |

| he

she |

lo

la |

them |

los (masculine or mixed gender group)

las (feminine group) |

The direct object pronoun comes before the verb in most cases. If the sentence is negative, the pronoun comes between the negative word (“no”) and the verb.

When there are two verbs – for example the conjugated verb and an infinitive, you can correctly write it two ways. You can put the direct object pronoun in front of the conjugated verb or attach it to the end of the infinitive.

Lo necessito ver. – I must see it.

Necissito verlo. – I must see it.

Direct Object Pronouns

First of all you must remember that a direct object in a sentence is the person, event or thing affected by the verb. The main difference between the use of the direct object pronouns in Spanish and English is their placement. While in English they substitute the direct object (and its article) and are placed where the original object was, in Spanish this pronoun is placed in front of the verb, replacing also any article used with the object previously.

| Singular |

Plural |

| Me (me) |

Nos (us) |

| Te (you) |

Os (you [all]) |

| *Lo/la (him/her/it) |

*Los/las (them: masculine/feminine/neuter) |

*The pronouns ‘le’ or ‘les’ are sometimes used as direct object pronouns. Its use carry some subtle differences in meaning.

Some examples:

|

Spanish |

English |

| Direct objectexpressed |

(Tú) llevas el libro |

You take/carry the book |

| Direct objectpronoun |

(Tú) lo llevas |

You take/carry it |

| Direct objectexpressed |

Ella rompe la silla |

She breaks the chair |

| Direct objectpronoun |

Ella la rompe |

She breaks it |

| Direct objectexpressed |

Ustedes secuestran losperros |

You [all] kidnap the dogs |

| Direct objectpronoun |

Ustedes los secuestran |

You [all] kidnap them |

| Direct objectexpressed |

El interrumpe la fiesta |

He interrupts the party |

| Direct objectpronoun |

El la interrumpe |

He interrupts it |

Indirect Object Pronouns

The indirect object tells “To whom?” or “For whom?” the action of the verb is performed.

| English Indirect Object Singular Pronoun |

Spanish Indirect Object Singular Pronoun |

English Indirect Object Plural Pronoun |

Spanish Indirect Object Plural Pronoun |

| me |

me |

us |

nos |

| you |

te (familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

le (formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

you (as in all of you) |

os (informal)

les (formal masculine and mixed gender groups -used in Spain) |

| he

she |

le |

them |

les |

The indirect object pronoun comes before the verb in most cases. If the sentence is negative, the pronoun comes between the negative word (“no”) and the verb.

When there are two verbs – for example the conjugated verb and an infinitive, you can correctly write it two ways. You can put the indirect object pronoun in front of the conjugated verb or attach it to the end of the infinitive.

Le volvo dar un libro

Volvo darle un libro.

Basic Spanish Pronouns

Indirect Object Pronouns

An indirect object is usually a person receiving the direct object. The pronouns in Spanish are basically the same as the ones used for the direct objects, with the exception of the third person. It is important to remember that in Spanish, anytime that an indirect object is expressed, the pronoun must be present even if the indirect object is expressed in some other way (i.e., prepositional clause).

| Singular |

Plural |

| Me (me) |

Nos (us) |

| Te (you) |

Os (you [all]) |

| Le/se (him/her/it) |

Les/se (them) |

As you see, we have one that can be used only for the singular (le), one used only for the plural (les), and yet another one (

se) that can be used for both! Nevertheless, the ‘

se‘ form is used only when the direct object pronoun is also used for reasons that seem to be primarily aesthetic (such as the use of the ‘n’ with the indefinite article in English: “an apple” vs. “a apple”). Although you’ll see the pesky ‘se’ everywhere in standard writing in Spanish (i.e., newspaper articles, literature, manuals, etc.), you should be aware that there are many uses of ‘se’, and that it’s not always used as an indirect object pronoun. Just

click here to see some other uses.

First, let’s see a few examples where we substitute the indirect object without using the direct object pronoun, and then we’ll see how these two pronouns act together.

|

Spanish |

English |

| With prepositional clause |

(Tú) Le das el libro aPedro |

You give the book toPedro |

| No prepositional clause |

(Tú) Le das el libro |

You give him the book [incorrect to express a prepositional clause]. |

| With prepositional clause |

Yo te doy el libro [a ti: redundant/emphasis] |

I give the book to you |

| No prepositional clause |

Yo te doy el libro |

I give you the book. |

Note how in both languages we can use the prepositional clause to know who is receiving the book. The prepositional clause is mainly used for clarification or for emphasis. Generally, in Spanish the prepositional clause is used at the end, whereas in English it would be incorrect to use it sometimes, as in the second sentence. In that case, we can identify the indirect object by using the name: “You give Pedrothe book.”

Using the Direct and Indirect Object Pronouns at the Same Time

When both pronouns are used, they will continue to be placed in front of the verb (linguists say that these pronouns become part of the verb). The order a declarative sentence will follow when both pronouns are present is: subject-indirect object pronoun-direct object pronoun-verb, or

SIODOV for short. Remember that you might not see the subject expressed at the beginning of the sentence due to the fact that it is implied in the verb. However, a personal pronoun or name of the subject could be placed at the beginning of the sentence.

- Direct object

- Indirect object

| Spanish |

English |

| (Yo) te doy el libro [a ti] |

I give the book to you |

| (Yo) te lo doy |

I give it to you [I give you it] |

| (Nosotros) les damos el libro a lasniñas |

We give the book to the girls |

| (Nosotros) se lo damos |

We give it to them |

Direct Object and Indirect Object Pronouns in the Same Sentence

When you have both a direct object pronoun and an indirect object pronoun in the same sentence, the indirect object pronoun comes first.

Yo le los doy. – I gave them to him.

Possessive Pronouns

| English Possessive Singular Pronoun |

Spanish Possessive Singular Pronoun |

English Possessive Plural Pronoun |

Spanish Possessive Plural Pronoun |

| mine |

el mío / la mía

los míos / las mías |

ours |

el nuestro / la nuestra

los nuestros / las nuestras |

| your, yours |

el tuyo / la tuya

los tuyos / las tuyas

(familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

l suyo / la suya

los suyos / las suyas

(formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

yours (as in all of you) |

el vuestro / la vuestra

los vuestros / las vuestras (Familiar)

el suyo / la suya

los suyos / las suyas

(Formal) |

| his

hers |

l suyo / la suya

los suyos / las suyas |

theirs |

el suyo / la suya

los suyos / las suyas |

This list differs slightly in usage from possessive pronoun/adjectives. The list is here:

| English Singular Pronoun – Adjectives |

Spanish Singular Pronoun – Adjectives |

English Plural Pronoun – Adjectives |

Spanish Plural Pronoun – Adjectives |

| my |

mi/mis |

our |

nuestro – nuestra

nuestros – nuestras |

| your, yours |

tu/tus

(familiar form used with friends, co-workers, children)

su/sus

(formal form used with superiors, strangers, children to adults) |

yours (as in all of you) |

vuestro – vuestra

vuestros – vuestras (Familiar)

el suyo / la suya

los suyos / las suyas

(Formal) |

| his

her |

su/sus |

theirs |

su – sus |

Here are several sample sentences to show the difference in usage;

Mi gato es bonito. – My cat is pretty. (Possessive adjective – pronoun in which my describes the noun cat)

El mio es bonito – Mine is pretty. (The possessive pronoun mine alone with cat inferred).

Another way one can express possession is to say:

El gato es de ella. – The cat is hers.

Notice that the article is not in front of the ella.

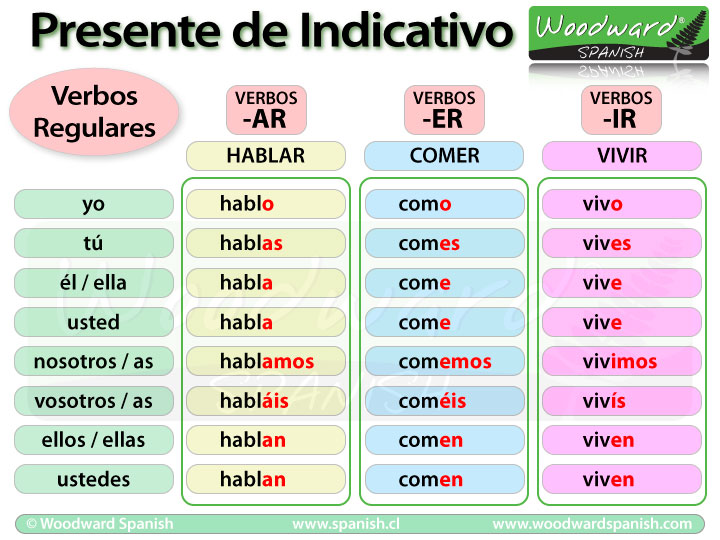

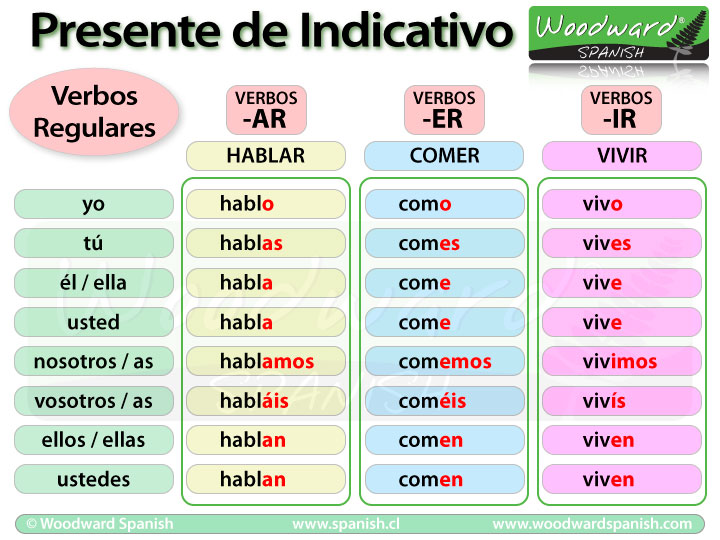

Present Tense in Spanish

Spanish Grammar Rules: El Presente Indicativ

In Spanish, verbs are classified into three types.

- Verbs ending in -AR,

- Verbs ending in -ER

- Verbs ending in -IR.

Spanish Regular Verbs in Present Tense

With regular verbs in Spanish, only the ending part of that verb (the

-ar,

-er or

-ir part) changes depending on who does the action. However, unlike English, there is a different ending for each subject (pronoun).

To begin, we will show you how to conjugate the verb in the present tense:

(Notice how the part of the verb in red is the part that changes)

Before you continue reading, make sure you know about

Subject Pronouns in Spanish (yo, tú, él etc.).

If you have the verb

Hablar (to speak) and you want to say “I speak”. You just remove the last two letters of the verb (in this case remove the

-ar) and add the letter -O to the end to create the conjugated verb

Hablo which means “I speak”.

Another example: if you want to say “They eat”, we take the original verb, in this case

Comer, we remove the ending (

-er) and then add -EN to the end (because

ellos = they). We now have

Comen (they eat).

You will notice that certain verb endings are repeated. For example for YO (I) we take off the ending for all regular verbs and add the -O to the root (main part) of the verb.

Also see how the only difference between -ER verbs and -IR verb endings is when we use

nosotros (we) and

vosotros (you/plural/informal).

The subject pronoun (yo, tú, nosotros etc.) is often omitted before the verb since we normally know who the subject (the person doing the action) is because of the verb’s ending.

For example: If you say “Hablamos español” (we speak Spanish). You don’t need to put the pronoun

nosotros before the verb because we know that when we say

hablamos, it refers to

nosotros (we). So often you will hear or just read “Hablamos español” without the pronoun

nosotros.

Basic Spanish Conversation Phrases

Conversational Phrases

Hola! (Hello). Estas listo para aprender Espanol? (Are you ready to learn some Spanish?). In this lesson, we will go over some basic phrases that are commonly used in Spanish.

Greetings

Let’s begin by looking at some common casual and formal greetings.

Casual Greetings

- Hola! (Hello)

- Como estas? (How are you?)

- Como te va? (How’s it going?)

- Que tal? (What’s up?)

- Que pasa? (What’s happening?)

- Como esta usted? (How are you?)

- Buenas tardes (Good evening, but also Good afternoon)

- Buenos dias (Good morning)

- Buenas noches (Good night)

Good Bye

Okay, now that we know some formal and informal ways to greet someone in Spanish, let’s practice some ways to say good bye.

- Nos vemos (See you later)

- Hasta luego (later)

- Adios (Bye)

- Adios (Bye)

- Que pase un buen dia (Have a nice day)

- Hasta pronto (See you soon)

Example 1

Now, let’s practice what we learned by paying attention to a conversation among two friends, Shirley and Erick.

Shirley: Hola (hello) Erick!

Erick: Hola (hello) Shirley! Como estas? (How are you?)

Shirley: Bien, gracias. (Fine, thank you)

Erick: Como esta tu familia? (How is your family?)

Shirley: Todos bien. (Everyone is well). Y tu familia? (and your family)

Erick: Bien también (Fine as well).

Shirley: Que vas a hacer hoy, Erick? (What are you doing today?)

Erick: Nada (nothing). Y tu? (and you?)

Shirley: Voy a estudiar un poco. ( I am going to study a little bit)

Erick:Bueno, me tengo que ir (well, I have to go). Nos vemos (see you later).

Shirley: Adios (bye).

Miscellaneous Phrases

Now let’s look at some basic miscellaneous Spanish questions.

- Tengo hambre (I am hungry)

- Tengo sed (I am thirsty)

- Estoy aburrido (I am bored)

- Tengo sueno (I am sleepy)

- Estoy cansado (I am tired)

- Mi comida favorita es la pizza (My favorite food pizza)

- Yo quiero ir al cine (I want to go to the movies)

- Yo no quiero ir al cine (I don’t want to go to the movies)

- Tengo tarea (I have homework)

- No tengo tarea (I don’t have homework)

- Tienes tarea? (Do you have homework?)

- No entiendo ( I don’t understand)

- Entiendo (I understand)

- Entiendo un poco (I understand a little)

Example 2

Now let’s practice again. This time we will be paying attention to a conversation that a family has during lunch.

Axel: mama, tengo hambre (mom, I am hungry)

Mom: Entiendo (I understand), I am serving the food already.

Clarice: mama, tengo sed (Mom, I am thirsty)

Mom: Clarice, sirvete (Clarice, serve yourself), I am busy getting the food ready, Sweetheart.

Dad: Axel, tienes tarea? (Axel, do you have homework?)

Axel: Si, papa. (yes, dad)

Dad: Y tu Clarice, tienes tarea? (And you Clarice, do you have homework?)

Clarice: No tongue tarea papa (I don’t have homework dad)

Axel: Mom, what are we eating?

Mom: Quesadillas

Axel: Ah, I wanted pizza, mi comida favorite es la pizza (my favorite food is pizza)

Mom: Si Axel, lo se (Yes Axel, I know)

Well done! Hasta pronto (see you later).

Example 3

Now, let’s do this last one! Let’s look at a conversation between Franco and Cindy.

Franco: Como estuvo tu dia, Cindy? (How was your day, Cindy?)

Cindy: no muy bien (not so well). Estoy bien cansada ( I am really tired).Y tu, Franco? (And you, Franco?). Como estuvo tu día (How was your day?).

Franco: Yo tuve un buen día (I had a good day).

Cindy: Tienes planes para este fin de semana? (Do you have plans for this weekend?).

Franco: Si (Yes). Voy a ir al juego de Basquetbol (I am going to the Basketball game).

Cindy: Que padre (Cool).

Franco: Y tu, Cindy? (And you, Cindy?).

Cindy: Yo voy ir a visitar a mi familia el Sabado (I am going to visit my family on Saturday), y el Domingo voy a ir al parque (and Sunday I am going to the park).

Franco: y a la Iglesia (and to church on Sunday).

Spanish Phrases for Travelers

Greetings, Basic Manners, and Useful Words

Buenos días (Good morning, pronounced: boo-eh-nos dee-ahs)

Buenas tardes (Good afternoon, pronounced: boo-eh-nas taar-dehs)

Buenas noches (Good evening/good night, pronounced: boo-eh-nas noh-ches)

Hola (Hello, pronounced: oh-lah)

Hasta luego (So long, pronounced: ahs-tah loo-eh-goh). This is to say bye when you expect to see someone later on, such as your hotel receptionist. Say adiós (Good bye, pronounced: ah-dee-os) when you are saying ‘bye’ for good. Also, Spanish speakers say chao (bye, pronounced: chah-oh) to mean ‘see you later’, ‘see you soon’, or ‘bye’.

Mucho gusto (Glad to meet you, pronounced: moo-choh goose-toh)

Permiso (Excuse me, pronounced: pehr-mee-soh). This is to ask people to get out of the way.

Disculpe (Sorry, pronounced: dees-kool-peh). This is when you have accidentally bumped someone or any other similar situation.

Por favor (Please, pronounced: pohr fah-bor)

Gracias (Thanks, pronounced: grah-see-ahs)

De nada (You’re welcome, pronounced: deh nah-dah

¿Habla inglés? (Do you speak English?, pronounced: ah-blah een-glehs)

Useful words you need to know are:

el aeropuerto (the airport, pronounced: ehl ah-eh-roh-poo-ehr-toh)

el pasaje (the ticket, pronounced: ehl pah-sah-heh). Note that, in Spain, people say el billete instead, which is pronounced: ehl bee-yeh-teh)

el pasaporte (the passport, pronounced: ehl pah-sah-pohr-teh)

el viaje (the trip, pronounced: ehl bee-ah-heh)

las vacaciones (the vacation, pronounced: lahs bah-kah-see-ohnehs)

At the Hotel

¿Cuánto cuesta la habitación? (How much is the room? pronounced: Koo-ahn-toh koo-ehs-tah la ah-bee-tah-see-on)The word ‘hotel’ is spelled exactly the same in Spanish and is pronounced ‘oh-tel’. These are useful phrases in hotels:

¿Incluye desayuno? (Does it include breakfast? pronounced: een-kloo-yeh deh-sah-yoo-noh)

¿Incluye impuestos? (Does it include taxes? pronounced: een-kloo-yeh eem-poo-es-tos)

Necesito una habitación para fumadores (I need a room for smokers, pronounced: neh-seh-see-toh oo-nah ah-bee-tah-see-on pah-rah foo-mah-doh-res).

Necesito una cama extra (I need an extra bed, pronounced: neh-seh-see-toh oo-nah kah-mah eks-trah)

¿Puedo pagar con tarjeta de crédito? (Can I pay with credit card?, pronounced: poo-eh-doh pah-gar kohn taar-heh-tah deh kreh-dee-toh)

Tip: Note that the question ¿Cuánto cuesta? (How much is it?) is useful in many situations. For instance, if you are shopping and you want to find out the price of anything, all you have to do is ask this question while pointing at what you want to buy.

At a Restaurant

The word ‘restaurant’ is restaurante in Spanish. The pronunciation is ‘rehs-tah-oo-rahn-teh’.

These are useful phrases in restaurants:

Una mesa, por favor (A table, please, pronounced: oo-nah meh-sah pohr fah-bor). If you wish to ask for a table for two, three, or more people, add the following expression with the number in Spanish that represents the number in your party: para dos (for two), para tres (for three), etc. after saying una mesa. For instance, una mesa para dos, por favor.

¿Puedo ver el menú, por favor? (Can I see the menu, please?, pronounced: poo-eh-doh vehr el meh-noo pohr fah-bor)

While you could just point at what you wish to have on the menu, the following words are useful when ordering:

Para la entrada, quiero… followed by the name of the dish you see on the menu. (For an appetizer, I want…, pronounced: pah-rah la ehn-trah-dah kee-eh-roh).

Spanish Irregular Verbs in Present Tense

The following verbs are only irregular in the first person (singular). The rest of the conjugations are as normal (see regular verbs above).

I.- First Person Verbs ending in -Y

The following verbs are a part of this group:

Estar (to be) –

Dar (to give)

| Subject |

Estar |

| Yo |

estoy |

| Tú |

estás |

| Él |

está |

| Ella |

está |

| Usted |

está |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

estamos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

estáis |

| Ellos / Ellas |

están |

| Ustedes |

están |

- Yo estoy feliz. (I am happy)

- Yo estoy en mi casa. (I’m at home)

- Yo doy propinas (I give tips).

II.- First Person Verbs ending in -GO

The following verbs are a part of this group:

Hacer (to do) –

Poner (to put) –

Salir (to go out) –

Valer (to cost/be worth)

| Subject |

Hacer |

| Yo |

hago |

| Tú |

haces |

| Él |

hace |

| Ella |

hace |

| Usted |

hace |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

hacemos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

hacéis |

| Ellos / Ellas |

hacen |

| Ustedes |

hacen |

- Yo hago mis tareas (I do my homework).

- Yo pongo la leche en el refrigerador.

- Yo salgo con mis amigos. (I go out with my friends)

- Yo valgo mucho (I’m worth it)

III.- First Person Verbs ending in -ZCO

Verbs that end in

-cir and

-cer change to

-zco in third person. The following verbs are a part of this group:

Conducir(to drive) –

Conocer (to know) –

Traducir (to translate)

| Subject |

Conducir |

| Yo |

conduzco |

| Tú |

conduces |

| Él |

conduce |

| Ella |

conduce |

| Usted |

conduce |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

conducimos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

conducís |

| Ellos / Ellas |

conducen |

| Ustedes |

conducen |

- Yo conduzco mi coche. (I drive my car)

- Yo conozco a muchas personas. (I know many people)

- Yo traduzco canciones. (I translate songs)

Remember these verbs are only irregular in the first person (singular), the rest of the verb has the same rules as regular present tense conjugations.

Spanish Verbs that have Stem Changes

There are four types of verbs where the stem of the verb is irregular and changes. In the present tense these are verbs that change their stem from O to UE, from U to UE, E to IE, and E to I. Note that this stem change does

nothappen when the verb is for

nosotros o

vosotros (these maintain the original stem of the verb).

I.- Stem changes from O to UE

The letter “

O” in the stem of the infinitive verb changes to “

UE” in the conjugations.

| Subject |

Almorzar |

| Yo |

Almuerzo |

| Tú |

Almuerzas |

| Él |

Almuerza |

| Ella |

Almuerza |

| Usted |

Almuerza |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

Almorzamos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

Almorzáis |

| Ellos / Ellas |

Almuerzan |

| Ustedes |

Almuerzan |

- Yo almuerzo con mis amigos. (I have lunch with my friends)

- Tú almuerzas todos los días en un restaurante. (You have lunch in a restaurant every day)

- Ellos almuerzan comida chilena. (They have Chilean food for lunch)

II.- Stem changes from E to IE

The letter “

E” in the stem of the infinitive verb changes to “

IE” in the conjugations.

| Subject |

Sentir |

| Yo |

siento |

| Tú |

sientes |

| Él |

siente |

| Ella |

siente |

| Usted |

siente |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

sentimos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

sentís |

| Ellos / Ellas |

sienten |

| Ustedes |

sienten |

- Ellos sienten frío. (She feels cold)

- Tú sientes un dolor de cabeza. (You have a headache)

- Él siente una presencia. (He feels a presence)

III.- Stem changes from E to I

The letter “

E” in the stem of the infinitive verb changes to “

I” in the conjugations.

| Subject |

Pedir |

| Yo |

pido |

| Tú |

pides |

| Él |

pide |

| Ella |

pide |

| Usted |

pide |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

pedimos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

pedís |

| Ellos / Ellas |

piden |

| Ustedes |

piden |

- Yo pido una bebida. (I ask for a drink)

- Usted pide un vaso de agua. (You ask for a glass of water)

- El animador pide un aplauso para el artista. (The presenter asks for applause for the artist)

IV.- Stem changes from U to UE

The letter “

U” in the stem of the infinitive verb changes to “

UE” in the conjugations. Note that the verb

Jugar is the only verb that is irregular in this way.

| Subject |

Jugar |

| Yo |

juego |

| Tú |

juegas |

| Él |

juega |

| Ella |

juega |

| Usted |

juega |

| Nosotros / Nosotras |

jugamos |

| Vosotros / Vosotras |

jugáis |

| Ellos / Ellas |

juegan |

| Ustedes |

juegan |

- Yo juego en mi pieza. (I play in my room)

- Tú juegas fútbol. (You play football)

- Usted juega baloncesto. (You play basketball)

Prepositions of Place

Spanish Grammar Rules

A preposition of place is used to show the relationship of two or more things in regards to location or position.

When translating

To Be + Preposition in English (e.g. The dog

is next to the tree), the verb

Estar (in its correct form) is used before the preposition of place. (e.g. El perro

está al lado del árbol).

Position of the preposition

In English a preposition sometimes appears at the end of a sentence, however in Spanish it is NOT possible to end a sentence with a preposition.

Prepositions in Spanish are always followed by an object (a noun or pronoun).

- preposition of place + object

See the examples that appear below.

Prepositions of Place in Spanish with examples

al lado de = next to / beside

- Al lado de mi casa hay una farmacia.

- Ana trabaja al lado de un hermoso parque.

alrededor de = around

- Los niños están jugando alrededor del árbol.

- Hay anillos alrededor de la planeta Saturno.

cerca de = near / close to

- Cerca de tu casa hay un centro comercial.

- Claudia vive cerca de una carretera.

debajo de = below / under

- Tus zapatos están debajo de ese mueble.

- Al él no le importa si tiene que pasar debajo de la escalera.

delante de (= frente a / enfrente de) = in front of / before / ahead of

- Delante de José hay un hombre que habla mucho.

- No me gusta que caminen lento delante de mi.

dentro de = in / inside / within

- Hay una sorpresa dentro de la caja.

- Sus llaves están dentro de la cartera.

detrás de = behind

- Detrás de ti hay un zombi.

- En la casa que está detrás del cerro hay unos lindos rosales.

en (= dentro de) = in / inside

- Nosotros vivimos en Chile.

- Alfredo está acostado en su cama.

en (= sobre) = on / on top of

- La cómida ya está en la mesa.

- Hay un reloj grande en la pared.

encima de = sobre = above / over / on / on top of

- El perro está encima de la cama otra vez.

- Nicolás está durminedo encima de la alfombra.

enfrente de = in front of /opposite

- Enfrente del colegio hay un edificio enorme.

- Pablo se sentó enfrente de Diego.

entre = between / among / in the midst of

- La farmacia esta entre la botillería y la carnicería.

- Puedes estacionarte entre esos dos carros.

frente a (= delante de algo / enfrente de) = in front of / opposite (facing)

- Cristina está sentada frente a Paula.

- El hospital está frente al supermercado

fuera de = outside

- El perro está fuera de la casa.

- Los niños durante su recreo juegan fuera de la sala de clases.

lejos de = far from

- Mariana trabaja lejos de su casa.

- Ellos viajarán lejos de aquí.

junto a (= al lado de) = next to

- La chica que me gusta está junto a la puerta.

- La escoba está junto a la pared.

sobre (= encima de) = on / on top of / upon

- Mis cuadernos están sobre el escritorio.

- Las cartas ya están sobre la mesa.

| PRESENT TENSE: regular verbs |

| 1. ABRIR : |

to open |

| Yo: |

abro |

Nosotros: |

abrimos |

| Tú: |

abres |

Vosotros: |

abrís |

| Ella: |

abre |

Ellos: |

abren |

|

| 2. APRENDER : |

to learn |

| Yo: |

aprendo |

Nosotros: |

aprendemos |

| Tú: |

aprendes |

Vosotros: |

aprendéis |

| Ella: |

aprende |

Ellos: |

aprenden |

|

| 3. ASISTIR : |

to attend |

| Yo: |

asisto |

Nosotros: |

asistimos |

| Tú: |

asistes |

Vosotros: |

asistís |

| Ella: |

asiste |

Ellos: |

asisten |

|

| 4. BAILAR : |

to dance |

| Yo: |

bailo |

Nosotros: |

bailamos |

| Tú: |

bailas |

Vosotros: |

bailáis |

| Ella: |

baila |

Ellos: |

bailan |

|

| 5. BARRER : |

to sweep |

| Yo: |

barro |

Nosotros: |

barremos |

| Tú: |

barres |

Vosotros: |

barréis |

| Ella: |

barre |

Ellos: |

barren |

|

| 6. BEBER : |

to drink |

| Yo: |

bebo |

Nosotros: |

bebemos |

| Tú: |

bebes |

Vosotros: |

bebéis |

| Ella: |

bebe |

Ellos: |

beben |

|

| 7. BORRAR : |

to erase |

| Yo: |

borro |

Nosotros: |

borramos |

| Tú: |

borras |

Vosotros: |

borráis |

| Ella: |

borra |

Ellos: |

borran |

|

| 8. CAMINAR : |

to walk |

| Yo: |

camino |

Nosotros: |

caminamos |

| Tú: |

caminas |

Vosotros: |

camináis |

| Ella: |

camina |

Ellos: |

caminan |

|

| 9. CANTAR : |

to sing |

| Yo: |

canto |

Nosotros: |

cantamos |

| Tú: |

cantas |

Vosotros: |

cantáis |

| Ella: |

canta |

Ellos: |

cantan |

|

| 10. COCINAR : |

to cook |

| Yo: |

cocino |

Nosotros: |

cocinamos |

| Tú: |

cocinas |

Vosotros: |

cocináis |

| Ella: |

cocina |

Ellos: |

cocinan |

|

| 11. COMER : |

to eat |

| Yo: |

como |

Nosotros: |

comemos |

| Tú: |

comes |

Vosotros: |

coméis |

| Ella: |

come |

Ellos: |

comen |

|

| 12. COMPRENDER : |

to understand |

| Yo: |

comprendo |

Nosotros: |

comprendemos |

| Tú: |

comprendes |

Vosotros: |

comprendéis |

| Ella: |

comprende |

Ellos: |

comprenden |

|

| 13. CORRER : |

to run |

| Yo: |

corro |

Nosotros: |

corremos |

| Tú: |

corres |

Vosotros: |

corréis |

| Ella: |

corre |

Ellos: |

corren |

|

| 14. DESAYUNAR : |

to have breakfast |

| Yo: |

desayuno |

Nosotros: |

desayunamos |

| Tú: |

desayunas |

Vosotros: |

desayunáis |

| Ella: |

desayuna |

Ellos: |

desayunan |

|

| 15. DIBUJAR : |

to draw |

| Yo: |

dibujo |

Nosotros: |

dibujamos |

| Tú: |

dibujas |

Vosotros: |

dibujáis |

| Ella: |

dibuja |

Ellos: |

dibujan |

|

| 16. ESCRIBIR : |

to write |

| Yo: |

escribo |

Nosotros: |

escribimos |

| Tú: |

escribes |

Vosotros: |

escribís |

| Ella: |

escribe |

Ellos: |

escriben |

|

| 17. ESCUCHAR : |

to listen |

| Yo: |

escucho |

Nosotros: |

escuchamos |

| Tú: |

escuchas |

Vosotros: |

escucháis |

| Ella: |

escucha |

Ellos: |

escuchan |

|

| 18. HABLAR : |

to speak |

| Yo: |

hablo |

Nosotros: |

hablamos |

| Tú: |

hablas |

Vosotros: |

habláis |

| Ella: |

habla |

Ellos: |

hablan |

|

| 19. LAVAR : |

to wash |

| Yo: |

lavo |

Nosotros: |

lavamos |

| Tú: |

lavas |

Vosotros: |

laváis |

| Ella: |

lava |

Ellos: |

lavan |

|

| 20. LEER : |

to read |

| Yo: |

leo |

Nosotros: |

leemos |

| Tú: |

lees |

Vosotros: |

leéis |

| Ella: |

lee |

Ellos: |

leen |

|

| 21. LIMPIAR : |

to clean |

| Yo: |

limpio |

Nosotros: |

limpiamos |

| Tú: |

limpias |

Vosotros: |

limpiáis |

| Ella: |

limpia |

Ellos: |

limpian |

|

| 22. LLEVAR : |

to wear, to carry |

| Yo: |

llevo |

Nosotros: |

llevamos |

| Tú: |

llevas |

Vosotros: |

lleváis |

| Ella: |

lleva |

Ellos: |

llevan |

|

| 23. MIRAR : |

to watch |

| Yo: |

miro |

Nosotros: |

miramos |

| Tú: |

miras |

Vosotros: |

miráis |

| Ella: |

mira |

Ellos: |

miran |

|

| 24. MONTAR : |

to ride |

| Yo: |

monto |

Nosotros: |

montamos |

| Tú: |

montas |

Vosotros: |

montáis |

| Ella: |

monta |

Ellos: |

montan |

|

| 25. NADAR : |

to swim |

| Yo: |

nado |

Nosotros: |

nadamos |

| Tú: |

nadas |

Vosotros: |

nadáis |

| Ella: |

nada |

Ellos: |

nadan |

|

| 26. PRESTAR : |

to lend |

| Yo: |

presto |

Nosotros: |

prestamos |

| Tú: |

prestas |

Vosotros: |

prestáis |

| Ella: |

presta |

Ellos: |

prestan |

|

| 27. RECIBIR : |

to receive |

| Yo: |

recibo |

Nosotros: |

recibimos |

| Tú: |

recibes |

Vosotros: |

recibís |

| Ella: |

recibe |

Ellos: |

reciben |

|

| 28. SUBIR : |

to go up, to rise |

| Yo: |

subo |

Nosotros: |

subimos |

| Tú: |

subes |

Vosotros: |

subís |

| Ella: |

sube |

Ellos: |

suben |

|

| 29. VENDER : |

to sell |

| Yo: |

vendo |

Nosotros: |

vendemos |

| Tú: |

vendes |

Vosotros: |

vendéis |

| Ella: |

vende |

Ellos: |

venden |

|

| 30. VIVIR : |

to live |

| Yo: |

vivo |

Nosotros: |

vivimos |

| Tú: |

vives |

Vosotros: |

vivís |

| Ella: |

vive |

Ellos: |

viven |

|

IR Ending Verbs

All IR ending verbs (that are regular) will have conjugation done in this way for present, past and future conditions. Some regular IR ending verbs are listed below these charts.

| Present Tense |

drop -IR ending and add: |

| I |

yo |

-o |

vivir (to live) => yo vivo (I live) |

| you (informal) |

tú |

-es |

tú vives (you live) |

| you (formal) |

usted |

-e |

ud. vive (you live) |

| we |

nosotros |

-imos |

nosotros vivimos (we live) |

| you (informal) |

vosotros |

-ís |

vosotros vivís (you all/they live) |

| you (formal) |

ellos, ustedes |

-en |

uds. viven (you all/they live) |

Common irregular verbs

Some verbs are so irregular that you will not be able to recognize when a conjugated form goes with the infinitive of the verb. The most irregular verbs in Spanish are also the most common, so you see the conjugated forms of these verbs often. Eventually, you will come to know the conjugated forms of these verbs so well that it may be difficult to remember the infinitive form. The verb ir means “to go .” Notice that the entire verb looks like the – ir infinitive ending, but it is conjugated nothing at all like a normal – ir verb. Also, notice that the conjugated forms of the verb ir in Table 1 look more like they come from some – ar verb with a v in it.

Once you get used to thinking that voy, vas, va, vamos, vais, and van all mean go or goes, it’s hard to remember that the infinitive that means “to go” is the verb ir.

Another really irregular verb is ser, which means “to be .” Be aware that each word that follows a pronoun in Table 2 is the entire form of the verb.

As luck would have it, the most common form, es, sounds a lot like its English equivalent “is .”

Not only is ser irregular in its conjugated forms, it also has to compete with the verb estar, which also means “to be.”

As luck would have it, the most common form, es, sounds a lot like its English equivalent “is .”

Not only is ser irregular in its conjugated forms, it also has to compete with the verb estar, which also means “to be.”

Irregular verbs in the yo form

Several common verbs in Spanish are completely regular verbs except for the yo form. These are usually called yo irregulars. To help you remember the irregular yo form as you work through this section, verbs with the same irregular yo form are grouped together.

–oy verbs

There are two extremely important verbs that are irregular only because the yo form of the verb ends in – oy: dar (to give) and estar (to be). As you can see in Tables 3 and 4, the rest of the forms of the verbs have regular endings.

Notice that the verb estar has accent marks on all forms except the first person yo and the first person plural nosotros/nosotras.

Notice that the verb estar has accent marks on all forms except the first person yo and the first person plural nosotros/nosotras.

–go verbs

There are many verbs with a yo form that ends in – go even though there is not a single letter g in the infinitive. Most of these verbs are regular in all of the rest of their forms.The four simplest and most common – go verbs are: The verbs hacer, poner, and valer are all regular – er verbs with an irregular yo form that ends in – go. Tables 5, 6, and 7 show how to conjugate each verb.

The verbs hacer, poner, and valer are all regular – er verbs with an irregular yo form that ends in – go. Tables 5, 6, and 7 show how to conjugate each verb.

Salir is a – go verb like poner, hacer, and valer. However, because it is an – ir verb, it will have the regular endings for an – ir verb, which differ slightly from – er verbs in the nosotros/nosotras and vosotros/vosotrasforms, as shown in Table 8.

Salir is a – go verb like poner, hacer, and valer. However, because it is an – ir verb, it will have the regular endings for an – ir verb, which differ slightly from – er verbs in the nosotros/nosotras and vosotros/vosotrasforms, as shown in Table 8.

The next two verbs, caer (to fall) and traer (to bring), follow the regular – er verb patterns of a – go verb, except for the irregular yo form, which adds an i to the conjugated form, as shown in Tables 9 and 10.

The next two verbs, caer (to fall) and traer (to bring), follow the regular – er verb patterns of a – go verb, except for the irregular yo form, which adds an i to the conjugated form, as shown in Tables 9 and 10.

Three common – go verbs also fall under another irregular category called stem‐changing verbs. The irregular – go ending of the yo form follows to keep the list of ‐ go verbs together. Normally you can’t predict that a verb will be irregular in its yo form unless you already know the verb. There is one rule that is consistent, however. If the infinitive of the verb ends in a vowel followed by – cer or – cir, theyo form of the verb ends in – zco. Here are the infinitive forms of some of the most common –zco verbs:

Normally you can’t predict that a verb will be irregular in its yo form unless you already know the verb. There is one rule that is consistent, however. If the infinitive of the verb ends in a vowel followed by – cer or – cir, theyo form of the verb ends in – zco. Here are the infinitive forms of some of the most common –zco verbs: These verbs are all conjugated exactly like conocer, which is the example used in Table 11. Use this table as model when you need to conjugate the other –zco verbs.