The dative case

The

dative case has four functions.

1) Indirect object

The

indirect object of a sentence is the being (usually a person, but sometimes a pet or an inanimate object) for whose benefit the subject is acting upon the direct object.. It answers the question:

To or

for whom does the subject <

insert meaning of verb here><

insert direct object here>?

EXAMPLES:

| Wir backen euch einen Kuchen.

We’re baking you a cake.

We’re baking a cake for you. |

“You” (pl). answers for whom the subject “we” is baking a cake. |

| Erik erzählt seinen Brüdern Witze.

Erik is telling his brothers jokes.

Erik is telling jokes to his brothers. |

“His brothers” answers to whom the subject “Erik” is telling jokes. |

| Den Touristen zeigt er die Kirche.

He shows the tourists the church.

He shows the church to the tourists. |

“The tourists” answers to whom the subject “he” is showing the church. |

Note that the dative case, when it denotes an indirect object in the sentence, can be and often is rendered into English using the preposition

to or

for. Because the dative case in German includes the meanings of these prepositions, those prepositions are not needed in German to designate the indirect object.

Note also that a sentence

cannot have an indirect object unless it first has a direct object. The indirect object is by definition to or for whom the subject does something to a direct object.

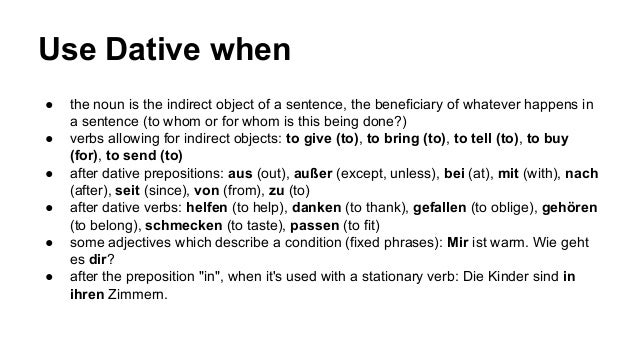

2) Object of a dative verb or dative construction

A number of verbs, adjectives, and idiomatic expressions require a dative object in German. The following verbs require a dative object and will never have an accusative object.

| antworten |

to answer |

imponieren |

to impress |

| begegnen |

to encounter |

Leid tun |

to be sorry |

| danken |

to thank |

nutzen |

to be useful to |

| dienen |

to serve |

passen |

to suit |

| drohen |

to threaten |

passieren |

to happen to |

| ein•fallen |

to occur to |

reichen |

to be enough |

| fehlen |

to be missing |

schaden |

to damage |

| folgen |

to follow |

schmecken |

to taste |

| gefallen |

to be pleasing to |

schwer•fallen |

to be difficult for |

| gehören |

to belong to |

vertrauen |

to trust |

| gelingen |

to succeed |

verzeihen |

to forgive |

| glauben |

to believe |

weh•tun |

to hurt |

| gratulieren |

to congratulate |

widersprechen |

to contradict |

| helfen |

to help |

zu•hören |

to listen to |

EXAMPLES:

| Hilfst du mir mit der Hausaufgabe?

Will you help me with the homework? |

“Me” is the object of the dative verb helfen. |

| Der Hund folgte dem Kind nach Hause.

The dog followed the child home. |

“The child” is the object of the dative verb folgen. |

| Das Geld reicht uns nicht.

The money is not enough for us. |

“Us” is the object of the dative verb reichen. |

Like dative indirect objects, the objects of dative verbs normally refer to persons. In the few instances where the verb objects are impersonal, they take the accusative case.

| Ich glaube dir (dat.).

I believe you. |

Ich glaube die Geschichte (acc.).

I believe the story. |

| Er verzeiht mir nie (dat.).

He’ll never forgive me. |

Er verzeiht den Fehler nie (acc.).

He’ll never forgive the mistake. |

In addition to the dative verbs, a number of adjectives and other idiomatic phrases are commonly used with dative objects. Here are some of them:

| ähnlich |

similar |

gleich |

same |

| angenehm |

pleasant |

leicht |

easy |

| begreiflich |

understandable |

nützlich |

useful |

| behilflich |

helpful |

peinlich |

embarrassing |

| bekannt |

known |

schädlich |

damaging |

| bequem |

comfortable |

teuer |

expensive |

| dankbar |

thankful |

verwandt |

related |

| fremd |

foreign |

willkommen |

welcome |

Notice in the examples below that the dative objects that accompany these adjectives are often rendered in English with an accompanying “to” or “for”. There is no need to add an additional preposition to the German sentence, since these meanings are included when the noun or pronoun is declined in the dative case.

EXAMPLES:

| Sie ist ihrem Vater sehr ähnlich.

She is very similar to her father. |

“(To) her father” is the dative object of the adjective “similar”. |

| Dieses Bett ist mir zu teuer.

This bed is too expensive for me. |

“(For) me” is the dative object of the adjective “expensive”. |

| Der Name war ihm sehr bekannt.

The name was well-known to him. |

“(To) him” is the dative object of the adjective “known” |

3) Object of a dative preposition

The object of an dative preposition must be in the dative case. These are the prepositions in German whose noun objects are always in the dative case:

| aus |

out of, from |

nach |

to, after, according to |

| außer |

except for |

seit |

since, for (+ time period) |

| bei |

at, with |

von |

from, by |

| gegenüber |

opposite, in relation to |

zu |

to |

| mit |

with; by means of |

|

|

EXAMPLES:

| Wir fahren mit der Bahn.

We’re traveling by train. |

“The train” is the object of the dative preposition mit. |

| Außer dir waren alle dabei.

Besides you, everyone was there. |

“You” is the object of the dative preposition außer. |

| Sie wohnt bei ihren Großeltern.

She’s living with her grandparents. |

“Her grandparents” is the object of the dative preposition bei. |

4) Object of a two-way preposition

Two-way prepositions are named as such because their objects are sometimes in the dative case and sometimes in the accusative case. Here are the two-way prepositions:

| an |

at, on (a vertical surface) |

über |

above, over |

| auf |

at, on (a horizontal surface) |

unter |

under |

| hinter |

behind |

vor |

in front of; before |

| in |

in |

zwischen |

between |

| neben |

beside |

|

|

When two-way prepositions are used with the dative case, they (1) designate a location, or (2) are in idiomatic expressions requiring the use of the dative.

EXAMPLES of 2-WAY PREPOSITIONS + DATIVE to indicate LOCATIONS:

| Sie sitzt gerade in der Bank.

She’s sitting in the bank. |

“In the bank” is a location describing where “she” is, hence intakes the dat. |

| Ich sitze neben ihm.

I am sitting next to him. |

“Next to him” is the location where the subject “I” is sitting, hence neben uses dat. |

| Grete hat Angst vor ihrem Vater.

Grete is afraid of her father. |

“Her father” is the dat.object of vor because the idiom Angst haben vor requires the use of the acc.case. |

In addition to the meanings listed , the two-way prepositions + dative have a range of idiomatic meanings, as the last example above shows:

Angst haben vor (+ dat.) =

to be afraid of.

Nouns and pronouns in the DATIVE CASE

Finally, here are some examples of nouns and pronouns in the dative case. Words and endings in

red indicate a change in form from the accusative.

| Nouns |

Personal Pronouns |

| masculine |

feminine |

neuter |

plural |

| dem Onkel

diesem Onkel

einem Onkel

keinem Onkel

unserem Onkel

|

der Tante

dieser Tante

einer Tante

keiner Tante

unserer Tante

|

dem Buch

diesem Buch

einem Buch

keinem Buch

unserem Buch |

den Kindern

diesen Kindern

Kindern

keinen Kindern

unseren Kindern |

mir

dir

ihm, ihr,ihm

uns

euch

Ihnen,ihnen |

The German dative case is generally used for the indirect object. The indirect object is often the receiver of the direct object. Take this sentence for example:

The German dative case is generally used for the indirect object. The indirect object is often the receiver of the direct object. Take this sentence for example:

- Der Bäcker gibt den Armen kein Brot – The Baker gives no bread to the poor

In that sentence there are two objects, a direct one, ‘bread‘, and the indirect one ‘the poor‘.

To identify which of both is the indirect object, you could simply ask yourself ‘To whom or for whom is the action being done?’. In most cases the indirect object is a person, but sometimes it could be an inanimate object as well.

Endings in the Dative case

Unlike the accusativ case discussed in the last lesson, the dative case not only affects the ending of the words linked to the noun, but it affects the noun itself as well.

| Article |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Definite |

dem Mann |

der Frau |

dem Kind |

den Tieren |

| Indefinite |

einem Mann |

einer Frau |

einem Kind |

– Tieren |

| Negative |

keinem Mann |

keiner Frau |

keinem Kind |

keinen Tieren |

| Possessive |

meinem Mann |

meiner Frau |

meinem Kind |

meinen Tieren |

Note that in the German dative case, an ‘-en‘ or a ‘-n‘ is added to the plural of the noun unless if that plural already ends with a ‘-s‘ or a ‘-n‘.

Personal Pronouns

All of the personal pronouns change from the nominative case to the dative case as shown in the next table:

| Singular Pronoun |

Definition |

Plural Pronoun |

Definition |

| mir |

me |

uns |

us |

| dir |

you – informal |

euch |

you – informal |

| ihm/ihr/ihm |

him/her/it |

ihnen |

they |

| Ihnen |

you – formal |

Ihnen |

you – formal |

Dative case after certain verbs

The Dative case comes after certain verbs no matter what role the noun/pronoun plays, and even if there is no direct object in the sentence.

| Verb |

Definition |

Verb |

Definition |

| antworten |

to answer |

gratulieren |

to congratulate |

| danken |

to thank |

helfen |

to help |

| drohen |

to threaten |

nutzen |

to be useful |

| fehlen |

to be missing |

passen |

to suit |

| folgen |

to follow |

schmecken |

to taste |

| gehören |

to belong to |

verzeihen |

to forgive |

| glauben |

to believe |

zuhören |

to listen to |

Dative case after certain prepositions

Certain prepositions always take the dative case no matter their position in the sentence, and even if there will be more than one dative noun within the sentence.

| Preposition |

Definition |

| aus |

from, out of |

| außer |

apart from |

| bei |

at, near |

| gegenüber |

opposite |

| mit |

with |

| nach |

after, to |

| seit |

since, for |

| von |

from |

| zu |

to |

Interrogatives in the Dative Case

In the dative, the interrogative pronoun ‘

wer‘ becomes ‘

wem‘, and the interrogative ‘

welcher‘ is declined according to the noun it’s attached to.

| Case |

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| Dative |

welchem |

welcher |

welchem |

welchen |

Impersonal Expressions

Numerous German expressions often use ‘

es‘ as their subject. They are called ‘

impersonal expressions‘ becuase they don’t identify a specific person or object as their subject. Often these expressions require a dative object.

For example:

- Es fällt mir ein – It occurs to me

- Es kommt dir vor – It appears to you

- Es scheint ihm – It seems to him

- Es gefällt dem Mann – It appeals to the man

Examples

Here are a few example sentences in which the dative nouns/pronouns are pointed out:

- Ich gebe meiner Schwester einen Hut – I’m giving a hat to my sister

- Wir folgen den Kindern – We are following the kids

- Sie kommt aus dem Museum – She is coming from the museum

- Wir fahren mit dem Zug – We’re riding the tra

|

|

|

|

Your team sits in three countries. And yet in the same office. |

|

In English:

In standard English, the indirect object is marked either by a prepositional phrase, word order or by certain forms of personal pronoun

(me, us, him, her, and

them). Thus: “He gave his girlfriend a diamond ring;” “He gave a diamond ring to his girlfriend;” “He gave her it;” or “He gave it to her.”

In German:

The dative case has several functions in German. It is marked in a variety of ways, with word order being the least important. The dative personal pronouns are:

| mir = me |

uns = us |

| dir = you |

euch = y’all |

|

Ihnen = you |

| ihm = him

ihr = her

ihm = it |

ihnen =they |

There are dative forms for other pronouns:

man becomes

einem, keiner becomes

keinem, and

wer becomes

wem. In colloquial speech,

jemand is more common, but

jemandem is possible. The reflexive pronoun “sich” can indicate either the accusative or dative form of

er,

sie (= she),

es,

Sie, or

sie (= they).

As with the nominative and accusative cases, articles and adjective endings mark the dative, but here there is no distinction between a “der-word” and an “ein-word”. However, endings are still different when there is no article at all. Note that plural nouns themseves receive an “-n” unless they already end in “-n” or “-s”:

1

| Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

Plural |

| dem roten Stuhl |

der neuen Lampe |

dem alten Buch |

den roten Stühlen |

| rotem Stuhl |

neuer Lampe |

altem Buch |

alten Büchern |

As in the accusative case, the so-called weak masculine nouns take an “-n” (or “-en”) in the dative (as well as in the genitive). Among these nouns are those that end in “-e” (except

Käse [cheese])

| nom.

acc.

dat. |

der Mensch

den Menschen

dem Menschen

[human] |

der Nachbar

den Nachbarn

dem Nachbarn

[neighbor] |

der Herr

den Herrn

dem Herrn

[lord; gentleman] |

der Held

den Helden

dem Helden

[hero] |

| nom.

acc.

dat. |

der Name

den Namen

dem Namen

[name] |

der Kunde

den Kunden

dem Kunden

[customer] |

der Junge

den Jungen

dem Jungen

[boy] |

der Experte

den Experten

dem Experten

[expert] |

| nom.

acc.

dat. |

der Glaube

den Glauben

dem Glauben

[belief] |

der Wille

den Willen

dem Willen

[will] |

der Gedanke

den Gedanken

dem Gedanken

[thought] |

der Türke

den Türken

dem Türken

[Turk] |

| nom.

acc.

dat. |

der Jude

den Juden

dem Juden

[Jew] |

der Russe

den Russen

dem Russen

[Russian] |

der Kollege

den Kollegen

dem Kollegen

[colleague] |

der Riese

den Riesen

dem Riesen

[giant] |

Other endings of weak nouns are “-ant,” “-arch,” “-ege,” “-ent,” “-ist,” “-oge,” “-om,” “-oph,” and “-ot.” Some examples:

| der Buddist

[Buddhist] |

der Katholik

[Catholic] |

der Protestant

[Protestant] |

der Pilot

[pilot] |

| der Student

[student] |

der Komödiant

[comedian] |

der Astronom

[astronomer] |

der Patriarch

[patriarch] |

| der Philosoph

[philosopher] |

der Fotograf

[photographer] |

der Enthusiast

[enthusiast] |

der Anthropologe

[anthropologist] |

Again: note that all of these nouns are masculine. Furthermore, their plural forms are the same as their dative singular forms: e.g.,

dem Studenten; [plural:] Studenten. (“Herr” is an exception:

den Herrn; [plural:] Herren).

Typically, dictionaries identify weak nouns by giving not only the plural but also the weak ending: “der Bauer (-n, -n)

farmer, peasant“. This first ending cited is actually that of the genitive case, but with weak nouns the dative and the genitive are usually identical. There are a few exceptions.

One neuter noun is also weak in the dative (and takes an “-ens” in the genitive):

| nom.

acc.

dat.

gen. |

das Herz

das Herz

dem Herzen

des Herzens

[heart] |

|

|

|

|

They need time to grow. We give it to them. The future has long been with us. [ = an ad promoting the use of coal while wind energy gets further developed] |

|

Uses of the dative case:

- 1) To designate the indirect object of a verb.

| Er erzählt seinen Kindern eine Geschichte. |

He tells his children a story. |

| Sie schreibt mir eine E-mail. |

She writes me an e-mail. |

| Er erklärte seiner Frau, warum er ihr ganzes Geld auf dieses Pferd setzte. |

He explained to his wife why he put all her money on this horse. |

| Er schreibt ihr einen langen Brief. |

He writes her a long letter. |

| Was schenken Sie ihrem Vater zum Geburtstag? |

What are you giving your father for his birthday? |

| Kannst du das der Polizei beweisen? |

Can you prove that to the police? |

- 2) When there are two objects (direct and indirect): a dative noun precedes an accusation noun; an accusative pronoun precedes a dative pronoun; and a pronoun always a noun:

| Ich gebe dem Mann ein Buch. |

| Ich gebe es dem Mann. |

| Ich gebe ihm das Buch. |

| Ich gebe es ihm. |

- It is possible to change this word order for emphasis, e.g. “Ich habe das Buch dem Mann gegeben (und nicht der Frau).”

|

|

|

|

His diet tips are radical. His training seems to contradict the laws of nature. Tim Ferriss brings his body into top form with unusual methods. |

|

- 3) Some verbs take the dative case even though logic might suggest the accusative:

| Sie glaubt mir nicht.2 |

She doesn’t believe me. |

| Ich danke dir. |

I thank you. |

| Kannst du mir verzeihen? |

Can you forgive me? |

| Helfen Sie mir! |

Help me! |

| Er hat ihr nicht geantwortet. |

He didn’t answer her. |

| Sie folgte ihrem Mann durch die Tür. |

She followed her husband through the door. |

| Das Kind gehorcht seinen Eltern gar nicht. |

The child doesn’t obey its parents at all. |

| Der Wagen gehört meiner Schwester. |

The car belongs to my sister. |

| Was ist dir geschehen? |

What happened to you? |

| Ich bin ihr oft in der Stadt begegnet. |

I often ran into her in town. |

| Sie ähnelt ihrer Mutter. |

She resembles her mother. |

| Du gleichst dem Geist, den du begreifst. |

You resemble the spirit that you comprehend. |

| Eine Entschuldigung genügt uns nicht. |

An apology isn’t enough for us. |

| Ich gratuliere dir zu deinem Nobelpreis. |

I congratulate you on your Nobel Prize. |

| Seine Rede hat mir sehr imponiert. |

His speech impressed me very much. |

| Deine Ausreden nützen uns wenig. |

Your excuses aren’t much use to us. |

| Sein Name fällt mir nicht ein. |

His name doesn’t occur to me. |

| Ich rate dir, mit dem Bus zu fahren. |

I advise you to go by bus. |

| Das schadet ihm nicht. |

That does him no harm. |

| Immer schmeichelt er seinem Chef. |

He flatters his boss all the time. |

| Du kannst mir trauen. |

You can trust me. |

| Widersprechen Sie mir nicht. |

Don’t contradict me. |

| Das widerspricht den Naturgesetzen. |

That contradicts the laws of nature. |

- 4) A number of verbs with the inseparable prefix “ent-“ or the separable “nach-“ take dative objects:

| Du kannst deinem Schicksal nicht entgehen. |

You can’t escape/avoid your fate. |

| Er konnte der Polizei nicht entkommen. |

He couldn’t escape the police. |

| Der Hund ist mir entlaufen. |

The dog ran away from me. |

| Sie will diesen Problemen nachgehen. |

She wants to investigate these problems. |

| Fahr los. Wir kommen dir später nach. |

Start driving. We’ll follow you later. |

| Der Hund läuft der Katze nach. |

The dog chases after the cat. |

- 5) Still other verbs with the separable prefixes “bei-“ and “zu-“ take dative objects:

| Sie steht ihrem Mann bei. |

She helps/stands by her husband. |

| Wir wollen der Sitzung beiwohnen. |

We want to attend the meeting. |

| Hören Sie mir bitte gut zu. |

Please listen to me closely. |

| Die Unbekannte lächelt ihm zu. |

The unknown woman smiles at him. |

| Während sie spielt, schauen ihr die Männer zu. |

The men watch her while she plays. |

| Sie ist dagegen, und ich stimme ihr zu. |

She’s against it, and I agree with her. |

| Er wollte einer linken Partei beitreten. |

He wanted to join a leftist party. |

- 6) With some verbs, the dative object would become the subject in an English translation:

| Die richtigen Leute fehlen uns. |

We lack/are missing the right people |

| Dein neuer Freund gefällt mir. |

I like your new friend. |

| Beim dritten Versuch gelingt es uns. |

We succeed on the third try. |

| Deine Frau tut mir Leid. |

I feel sorry for your wife. |

- 7) The so-called “dative of interest” establishes a point of view. Here too, the dative object can often be rendered as the subject in English:

| Es ist mir kalt. |

I’m cold. |

| Jetzt reicht’s mir aber! |

I’ve had enough of that! |

| Seine Haltung passt ihr nicht. |

She doesn’t like his attitude. |

| Ist Ihnen nicht wohl? |

Don’t you feel well? |

| Wie geht’s dir? |

How are you? |

| Das kommt mir irgendwie bekannt vor. |

That somehow seems familiar to me. |

| Ist der Stuhl dir unbequem? |

Is the chair uncomfortable for you? |

| Das war meinem Mann zu dumm. |

My husband found that too stupid. |

- 8) The “dative of interest” often appears with predicate adjectives or predicate nominatives:

| Das ist meiner Mutter besonders interessant. |

That’s especially interesting to my mother. |

| Meine Kinder sind mir eine einzige Freude. |

My children are nothing but a joy to me. |

| Das ist ihm sehr peinlich. |

That’s very embarrassing to him. |

| Sie ist ihrem Mann in allem weit überlegen. |

She vastly superior to her husband in all things. |

| Diese Mode ist Europäern völlig unbekannt. |

This fashion is wholly unknown to Europeans. |

| Wir sind Ihnen sehr dankbar. |

We’re very grateful to you. |

| Das ist dir bestimmt leicht. |

That’s surely easy for you. |

| Ihr Anruf ist uns sehr wichtig. |

Your call is very important to us. |

| Das ist mir unmöglich. |

That’s impossible for me. |

| Die Jacke ist ihr zu teuer. |

The jacket is too expensive for her. |

| Das scheint mir richtig zu sein. |

That seems correct to me. |

- 9) The dative can also indicate toward whom an action is directed, especially when parts of the body are involved.

| Sie haut ihm eins in die Fresse. |

She pops him one in the chops. |

| Sie klopft ihm auf die Schulter. |

She taps him on the shoulder. |

| Tut Ihnen der Kopf weh? |

Do you have a headache? |

| Ich muss meiner Tochter die Schuhe anziehen. |

I have to put my daughter’s shoes on (her). |

| Er hat ihr die Nase gebrochen. |

He broke her nose. |

| Ich will ihm den Kopf waschen |

“I’ll wash his head” (= I’m going to give him a piece of my mind). |

| Sie putzt ihm die Zähne. |

She brushes his teeth. |

- 10) Of course the reflexive is used when the the action is directed back toward the subject:

| Du sollst dir die Zähne putzen. |

You ought to brush your teeth. |

| Ich habe mir den Finger gebrochen. |

I broke my finger. |

| Er kämmt sich die Haare. |

He combs his hair. |

| Sie färbt sich die Haare. |

She dyes her hair. |

| Er rasiert sich die Beine. |

He shaves his legs. |

| Ich wasche mir die Hände in Unschuld. |

I will wash my hands in innocency (Psalms 26: 6) |

With prepositions:

|

|

|

|

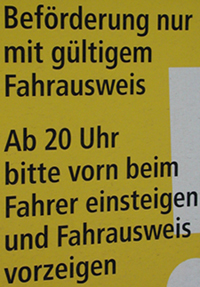

Conveyance only with a valid ticket. After 8 p.m. please enter at the front by the driver and show your ticket. |

|

The object of the following prepositions is always in the dative:

aus,

außer,

bei,

gegenüber,

mit,

nach,

seit,

von,and

zu. Note that “bei dem,” “von dem,” “zu dem,” and “zu der” are normally contracted:

| Die Katze sprang aus dem Fenster. |

The cat jumped out of the window. |

| Er war aus dem Häuschen. |

He was over the moon. |

| Außer deinem Bruder taugt deine Familie nicht viel. |

Except for your brother, your family isn’t worth much. |

| Sollen wir bei mir Essen? |

Should we eat at my place? |

| Die Mönche reden nicht beim Essen. |

The monks don’t talk while eating. |

| Bei diesem Wetter bleiben wir lieber zu Hause. |

In this weather it would be better to stay home. |

| Wer sitzt mir gegenüber? |

Who’s sitting across from me? |

| Er tanzt mit seiner Frau. |

He’s dancing with his wife. |

| Fährst du mit der Bahn oder mit dem Wagen? |

Are you going by train or by car? |

| Nach dem Film gehen wir zu dir. |

After the movie we’ll go to your place. |

| Seiner Mutter nach ist er ein Genie. |

According to his mother he’s a genius. |

| Sie arbeitet seit zwei Jahren in Berlin. |

She’s been working in Berlin for two years. |

| Viele Studenten bekommen Geld vom Staat. |

A lot of students get money from the state. |

| Sie ist die Frau von meinem Onkel. |

She’s my uncle’s wife. |

| Hast du was zum Schreiben? |

Do you have something to write with? |

| Rotkäppchen geht zur Großmutter |

Little Red Ridinghood is going to her grandmother’s. |

|

|

|

|

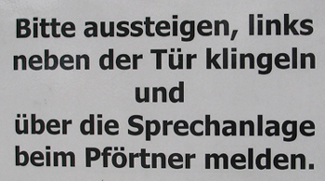

Please exit your car, ring (the bell) to the left of the door and announce yourself to the porter over the intercom. |

|

- Under certain circumstances the dative is used with the following “two-way” prepositions: an, auf, hinter, in, neben, entlang, über, unter, vor, and zwischen. When these prepositions delineate a spacial area, and the verb’s action or lack of action remains entirely within the area, they take the dative. If the verb indicates movement that crosses the border into that area, the preposition takes the accusative case):

| Die Gäste sitzen am Tisch. |

The guests are sitting at the table. |

| Der Hund liegt auf dem Teppich. |

The dog’s lying on the rug. |

| Sie arbeitet hinter dem Haus. |

She’s working behind the house. |

| Man kann nicht zwischen zwei Stühlen sitzen. |

You can’t sit between two chairs. |

- “an dem” and “in dem” are usually contracted:

| Er steht am Fenster. |

He stands at the window. |

| Es gibt einen Fremden im Haus. |

There’s a stranger in the house. |

|

|

|

|

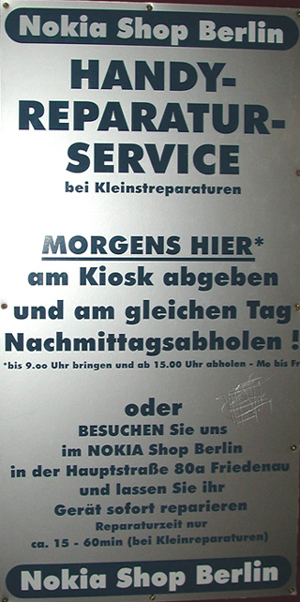

Cell Phone Repair Service for small repairs. Bring it in to the booth in the morning and pick it up on the same day in the afternoon. Or visit us in the Nokia Shop Berlin at Hauptstrasse 80a in Friedenau and have your phone repaired immediately. |

|

When these two-way prepositions define time, rather than space, they usually take the dative. The exceptions are

“auf”and

“über”:

| Am Montag machen wir die Wäsche. |

We do the laundry on Monday. |

| In der Nacht sind alle Katzen grau. |

At night all cats are grey [Any port in a storm]. |

| Er soll unter einer Stunde reden. |

He’s supposed to talk for under an hour. |

| Aber er hat über eine Stunde geredet. |

But he talked for over an hour. |

| Vor jedem Essen trinken wir ein Glas Portwein. |

We drink a glass of port before each meal. |

| Vor einem Jahr hat sie kein Deutsch gekonnt. |

A year ago she couldn’t speak any German. |

| Auf eine Woche Ausbildung folgte eine Pause. |

After a week of training there followed a pause. |

These two-way prepositions take the dative case in certain idioms, as well. A few examples:

| Sie arbeitet jetzt an einem Buch. |

She’s working on a book. |

| Das Kind hängt an mir. |

The child is attached to me. |

| Das Wasser ist am Kochen. |

The water’s boiling. |

| Ich zweifele an seinem guten Willen. |

I have doubts about his good will. |

| Sie hat lange an Krebs gelitten und ist dann an dieser Krankheit gestorben. |

She suffered from cancer for a long time and then died of this disease. |

| In Deutschland gibt es einen Mangel an Kindern. |

In Germany there’s a shortage of children. |

| Du bist schuld an meiner Erkältung. |

It’s your fault I have a cold. |

| Nimmst du am Programm teil? |

Are you taking part in the program? |

| Kuwait ist reich an �l. |

Kuwait has abundant oil. |

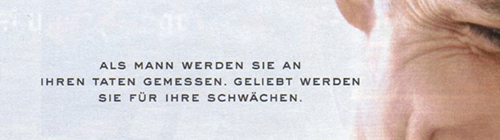

| Wir messen ihn an seinen Taten. |

We measure him by his deeds. |

|

|

|

|

As a man, you’re measured by your deeds. You’re loved for your weaknesses. |

|

| Sie besteht auf ihrem Recht. |

She insists on her rights. |

| Unter diesen Bedingungen bin ich bereit, es zu tun. |

Under these conditions I’m ready to do it. |

| Sie führen ein Gespräch unter vier Augen. |

They’re having a tête-à-tête. |

| Weil wir jetzt unter uns sind, können wir darüber reden. |

Now that we’re among ourselves we can talk about it. |

| Endlich habe ich diese Prüfung hinter mir. |

I’ve finally got this test out of the way. |

| Ich warne Sie vor dem Hund. |

I warn you about the dog. |

| Er war außer sich vor Wut. |

He was beside himself with fury. |

| Hast du wirklich Angst vor mir? |

Are you really afraid of me? |

| Kondome schützen vor AIDS. |

Condoms protect (you) from AIDS. |

| Diese Information soll zwischen meiner Mutter und mir bleiben. |

That information should stay between me and my mother. |

1 The so-called “der-words” are the articles

der,

die,

das;

dies-,

jed-,

jen-,

manch-,

solch-, and

welch-.

The “ein-words” are

ein,

kein, and the possessive pronouns:

mein,

dein,

sein,

ihr,

unser,

euer,

Ihr, and

ihr.

]]>

Like dative indirect objects, the objects of dative verbs normally refer to persons. In the few instances where the verb objects are impersonal, they take the accusative case.

Like dative indirect objects, the objects of dative verbs normally refer to persons. In the few instances where the verb objects are impersonal, they take the accusative case.

In addition to the dative verbs, a number of adjectives and other idiomatic phrases are commonly used with dative objects. Here are some of them:

In addition to the dative verbs, a number of adjectives and other idiomatic phrases are commonly used with dative objects. Here are some of them:

The German dative case is generally used for the indirect object. The indirect object is often the receiver of the direct object. Take this sentence for example:

The German dative case is generally used for the indirect object. The indirect object is often the receiver of the direct object. Take this sentence for example:

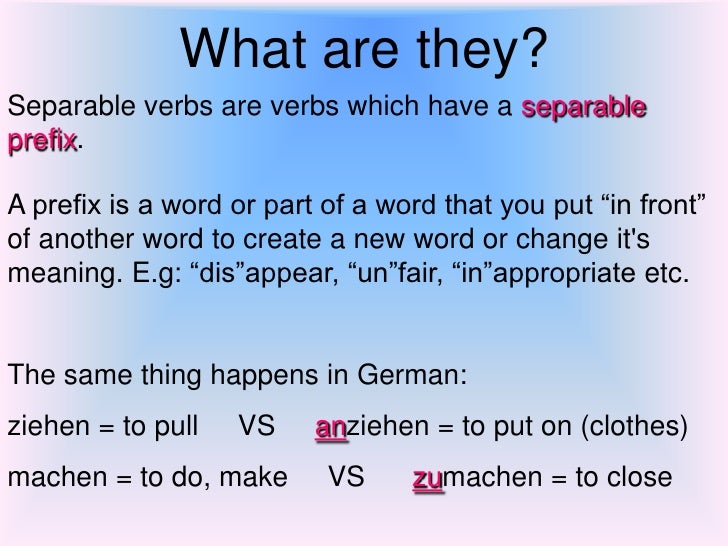

New words

New words

Possessive adjectives

Possessive adjectives