Preparation for A1, A2 German Exams in Coimbatore

German Speaking Test Modal Exam Video

German Language Course for Beginners (Level A1)

Level A1 (Basic User 1) of the Common European Framework for Reference of

Languages.

The curriculum for the A1 German language course includes:

- introducing oneself and others

- asking for someone’s name and origin

- greeting someone

- spelling in German

- starting a conversation

- stating and understanding figures, quantities, time and prices

- ordering and paying in a restaurant

- naming and asking for things/objects

- analysing simple graphs

- describing a flat or house

- describing a geographical location

- speaking about countries, cities, their languages

- making an appointment

- describing ones holiday

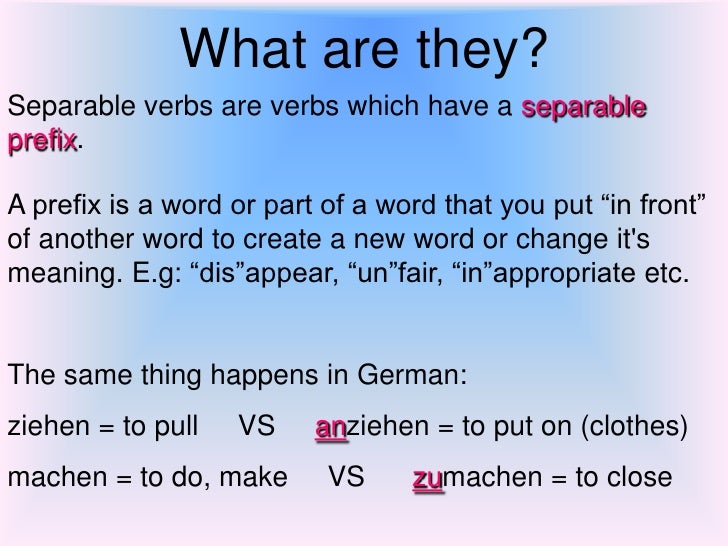

- talking about hobbies

- describing people, the clothes they wear

- understanding weather reports and describing the weather

- understanding short written messages, public notices and classified advertisements

- filling in personal details and basic information on forms

- writing brief personal messages/ Emails,

- formulating and responding to common everyday queries and requests.

- answering simple questions relating to everyday life,

- understanding what one hears in everyday situations, such as simple questions,

- instructions and messages, as well as messages on an answerphone, public

- announcements and brief conversations.

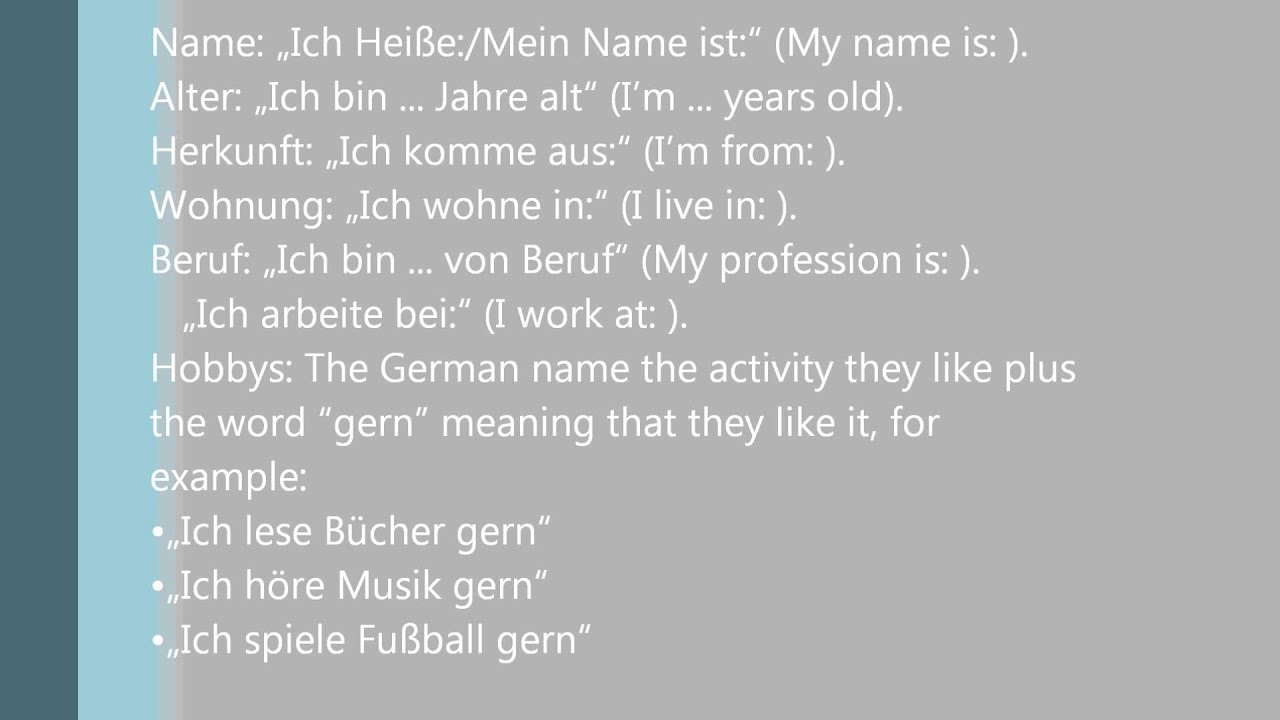

How to prepare for the A1 Level Sprechen part?

In the speaking part of the A1 German Examination as the introductory part the participants are led by two teachers who organise the Sprechen part .

The exam session may consist of four to five participants.

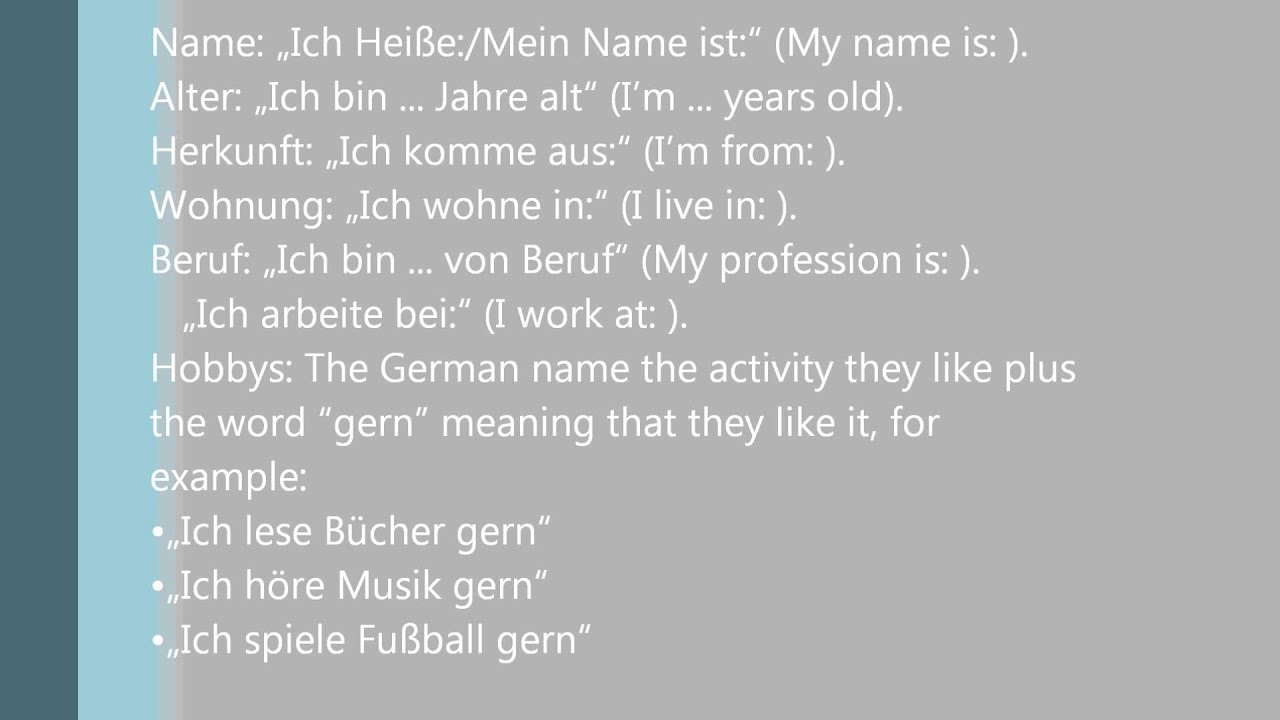

The first part of the speaking test consists of the following framework for the participants to introduce themselves one by one following an example by the presenter who normally may be from Goethe Institut.

1.Name?

2.Alter?

3.Land?

4.Wohnort?

5.Sprachen?

6.Beruf?

7.Hobby?

The participant has to start with giving his name and go on with how old he or she is , where he comes from, where he lives, what languages he speaks, what his profession is and finally what his hobbies are.

Well, it is as simple as that!

What does A1 mean? It means the proficiency level you have to be at in German, as per the Common European Framework of Reference for Language. You would have reached the A1 proficiency level when you are able to:

- Understand familiar, concrete expressions necessary to carry out the basic needs of day-to-day life.

- Introduce yourself to people and give personal details.

- Maintain limited communication with another person, provided he or she understands your limitations.

So you should be able to do things like ask and tell time, buy goods, order meals, and ask for simple directions.

With both the Goethe Exams, there are two portions of the A1 exam:

- A written examination that tests your listening, reading, and writing skills, which lasts 65 minutes.

- An oral examination that tests your speaking skills, which lasts 10 to 15 minutes.

So you should be able to do the following at an A1 level namely listening, reading, writing, and speaking.

To reach the A1 level, plan for about 75 to 100 total hours of studying. This means that if you study two hours a day, you could be ready in six to eight weeks.

When you’re in a German-speaking country, you’re bound to find yourself in a number of situations where you need to ask a lot of questions as you find your way around — for example, where the nearest bank is or how long the train will be delayed — or you may simply need to ask someone to speak more slowly. You many find the following vocabulary useful in various situations.

These expressions can help you get the attention of someone, excuse yourself, or ask someone to repeat himself:

-

Entschuldigung! (I’m sorry./Excuse me.)

-

Entschuldigen Sie, bitte! (Excuse me, please./I beg your pardon.)

-

Entschuldigung? (Pardon?)

-

Verzeihung bitte. (Excuse me./Pardon me.)

-

Verzeihung! (Sorry!)

-

Wie bitte? (Pardon?/Sorry?/I beg your pardon?) You use this phrase when you don’t understand what someone has said.

After you get the person’s attention, you may need to follow up with a request for help. The following are some common requests for getting help and asking someone to repeat himself or to speak more slowly:

-

Könnten Sie mir bitte helfen? (Could you help me, please?)

-

Könnten Sie das bitte wiederholen? (Could you repeat that, please?)

-

Könnten Sie bitte langsamer sprechen? (Could you please speak more slowly?)

In a restaurant, you can get service with the following expressions. Just remember to start with Entschuldigen Sie, bitte!

(

Excuse me, please!)

-

Was würden Sie zum Essen empfehlen? (What would you recommend to eat?)

-

Bringen Sie mir/uns bitte die Speisekarte/die Rechnung. (Please bring me/us the menu/check.)

-

Könnten Sie bitte einen Löffel/eine Serviette bringen? (Could you bring a spoon/a napkin, please?)

-

Ich hätte gern . . . (I’d like . . .) When ordering food or drink, add the item from the menu to the end of this phrase.

When you’re shopping in a department store or other large store, the following may help you navigate it more easily:

-

Wo ist die Schmuckabteilung/Schuhabteilung? (Where is the jewelry/shoe department?)

-

Wo finde ich die Rolltreppe/die Toiletten? (Where do I find the escalator/restrooms?)

-

Haben Sie Lederwaren/Regenschirme? (Do you carry leather goods/umbrellas?)

-

Wie viel kostet das Hemd/die Tasche? (How much does the shirt/bag cost?)

-

Könnten Sie das bitte als Geschenk einpacken? (Could you wrap that as a present, please?)

When you’re walking around town and need directions on the street, the following questions can help you find your way:

-

Wo ist das Hotel Vierjahreszeiten/Hotel Continental? (Where is the Hotel Vierjahreszeiten/Hotel Continental?)

-

Gibt es eine Bank/eine Bushhaltestelle in der Nähe? (Is there a bank/bus stop near here?)

-

Könnten Sie mir bitte sagen, wo die Post/der Park ist? (Could you tell me where the post office/park is, please?)

These questions come in handy when you’re taking public transportation:

-

Wo kann ich eine Fahrkarte kaufen? (Where can I buy a ticket?)

-

Wie viele Haltestellen sind es zum Bahnhof/Kunstmuseum? (How many stops is it to the train station/art museum?)

-

Ist das der Bus/die U-Bahn zum Haydnplatz/Steyerwald? (Is this the bus/subway to Haydnplatz/Steyerwald?)

-

Wie oft fährt die Straßenbahn nach Charlottenburg/Obermenzing?(How often does the streetcar go to Charlottenburg/Obermenzing?)

-

Ich möchte zum Hauptbahnhof. In welche Richtung muss ich fahren?(I’d like to go to the main train station. In which direction do I need to go?)

-

Von welchem Gleis fährt der Zug nach Köln/Paris ab? (Which track does the train to Cologne/Paris leave from?)

Dialogue

Read and listen to the following dialogue between two students:

Now try to understand the dialogue with the help of the following list of vocabulary.

Vocabulary:  What’s your name? (1st Part) — What’s your name? (1st Part) —  Wie heißt du? (1. Teil) Wie heißt du? (1. Teil)

|

| English |

German |

| Hello! |

Hallo! |

| I |

ich |

| I am… |

Ich bin … |

| how |

wie |

| you |

du |

| Your name is… |

Du heißt … |

| What is your name? |

Wie heißt du? |

| My name is… |

Ich heiße … |

| it |

es |

| it goes |

es geht |

| How is it going? |

Wie geht’s? (Longer: Wie geht es?) |

| me |

mir |

| good |

gut |

| I’m good. |

Es geht mir gut. (Shorter: Mir geht’s gut. Even shorter: Gut.) |

| you know |

du kennst |

| Do you know…? |

Kennst du …? |

| teacher |

Lehrer |

| yes |

ja |

| he |

er |

| His name is… |

Er heißt … |

| Mr. |

Herr |

| oh |

oh |

| thanks |

danke |

| until |

bis |

| then |

dann |

| See you! |

Bis dann! |

| on |

auf |

| again |

wieder |

| (to) see |

sehen |

| Goodbye! |

(Auf) Wiedersehen! |

Problems: Working with the dialogue

Hellos and Goodbyes

There are many ways of saying hello and goodbye in German; some of them are:

Vocabulary:  Greetings — Greetings —  Grüße Grüße |

| English |

German |

| Hello! |

Hallo!* |

| Servus! (used in southern Germany and eastern Austria, informal) |

| Moin! (used in northern Germany) |

| Good morning! |

Moin Moin! (used in northern Germany) |

| Guten Morgen!* |

| Morgen! (shorter) |

| Good day! |

Guten Tag!* |

| Tag! (used in Germany, shorter) |

| Good evening! |

Guten Abend!* |

| Hello! |

Grüß Gott! (used in southern Germany, Austria and South Tyrol) |

| Goodbye! |

Auf Wiedersehen!* |

| Wiedersehen! (shorter) |

| Bye! |

Tschüss!* |

| Tschau! (also spelled “ciao” as in Italian) |

| Servus! (used in southern Germany and eastern Austria, informal) |

| See you later! |

Bis später!* |

| See you! |

Bis dann!* |

| Bis bald!* |

| See you soon! |

Bis gleich! |

| Good night! |

Gute Nacht!* |

*You will need to know each expression with an asterisk (*) after it. The others, of course, would be useful to know if you are traveling to regions where they are used. (As you can see, the different German-speaking regions often have their own ways of saying hello and goodbye. However, you will not be required to know any of these less common phrases for any problems or tests.)

The more formal phrases are

guten Morgen,

guten Tag, and

auf Wiedersehen. The less formal ones are

tschüss,

Tag,

servus, and

ciao. The others are somewhat neutral on the formal-informal scale.

In German,

Herr and

Frau are used instead of

Mr. and

Mrs. before a last name; e.g.,

Mr. Schwarz –

Herr Schwarz.

Vocabulary:  Mr. & Ms. — Mr. & Ms. —  Herr und Frau Herr und Frau |

| English |

German |

| Mr. |

Herr |

| Mrs. |

Frau |

Frau is used for married and unmarried women. Some people still use

Miss –

Fräulein in spoken German but it is no longer used in written German since it is considered an inappropriate discrimination of unmarried women.

Literally,

der Herr means

the gentleman and

die Frau means

the woman. If you use these words without a last name after them, you have to use an article before them; e.g.,

der Herror

die Frau. This is actually just like in English. For example:

- The woman’s name is Mrs. Weiß – Die Frau heißt Frau Weiß.

Note also that the German translation of

the man is

der Mann and

the lady should be translated to

die Dame. Thus, without last names you would rather use these pairs:

- man and woman – Mann und Frau

- men and women – Männer und Frauen

- lady and gentleman – Dame und Herr

- ladies and gentlemen – Damen und Herren

Replies to Wie geht’s?

There are many ways to reply to the question

Wie geht’s? Here are some of them:

Vocabulary:  How are you? — How are you? —  Wie geht’s? Wie geht’s?

|

| English |

German |

| How are you? |

Wie geht’s? (longer: Wie geht es dir?)* |

| great |

prima |

| good |

gut |

| very good |

sehr gut |

| miserable |

miserabel |

| bad |

schlecht |

| not (so) good |

nicht (so) gut |

| O.K. |

ganz gut |

| all right |

Es geht so. (Or shorter: Geht so.) |

*The more formal form is

Wie geht es Ihnen?

After replying to the question, you could continue with:

- And how are you? — Und wie geht es dir? (formal: Und wie geht es Ihnen?)

Or shorter:

- And you? — Und dir? (or: Und selbst?; or formal: Und Ihnen?)

Lesson I.2: Wie heißt du? (2. Teil)The dialogue of this lesson is a conversation between two persons: Franz and Mr. Schwarz. While Franz uses the formal

Sie to address Mr. Schwarz, the latter uses the informal

du to address Franz. We also discuss some grammar:

subject pronouns and some important verbs in the present tense.

Dialogue

In this short dialogue Mr. Schwarz uses the informal form

you –

du. while Franz uses the formal translation of

you –

Sie. When listening to the dialogue, try to find out how the word

Sie is pronounced.

Dialogue:  What’s your name? (2nd Part) — What’s your name? (2nd Part) —  Wie heißt du? (2. Teil) Wie heißt du? (2. Teil) |

| Franz |

Guten Morgen. Sind Sie Herr Weiß? |

| Herr Schwarz |

Nein, ich bin Herr Schwarz. Wie heißt du? |

| Franz |

Ich heiße Franz. Danke, Herr Schwarz. Ich bin spät dran. |

| Herr Schwarz |

Bitte, Franz. Ich bin auch spät dran. Bis später! |

| Franz |

Auf Wiedersehen! |

Problems: Listen carefully!

Vocabulary:  What’s your name? (2nd Part) — What’s your name? (2nd Part) —  Wie heißt du? (2. Teil) Wie heißt du? (2. Teil) |

| English |

German |

| Good morning. |

Guten Morgen. |

| you (formal) |

Sie |

| You are… (formal) |

Sie sind … |

| Are you…? (formal) |

Sind Sie …? |

| no |

nein |

| late |

spät |

| I am late. |

Ich bin spät dran. |

| You’re welcome. |

Bitte. |

| also |

auch |

| later |

später |

| See you later. |

Bis später. |

Sie and du

Why is Franz using the formal form of

you —

Sie while Mr. Schwarz is using the informal of

you —

du?

First of all you should realize that Franz addresses Mr. Schwarz with his last name while Mr. Schwarz addresses Franz with his first name. This is probably the most important rule: if you (would) address someone with his or her last name, you should use the formal

Sie. On the other hand, if you are using the first name, you should use

du. Anything else would sound funny.

Sie is the polite form. It is used to foreign people, and in order to testify respect against the interlocutor, for people you would address with Mr and Mrs.

So, when do Germans address other people with their first name and say

du?

- Some cases are very clear: children, relatives, and friends are always addressed with du. (Mr. Schwarz uses du because Franz is still a child. Otherwise Mr. Schwarz would either use Sie or Franz would also use du.)

- Students (at universities etc.) usually say du to other students and everyone else who is of their age or younger.

- The situation is not so clear for colleagues in companies. Fortunately, there is another rule for grown-ups: any two grown-ups address each other in the same way, either withdu or Sie, but never does only one of them use du and the other Sie. Thus, if in doubt, you can just copy how the other person addresses you.

- In all other situations you should use Sie. If a German thinks that it would be more appropriate to say du, he or she will be happy to suggest to use du. On the other hand, it is almost always considered impolite to go from du to Sie; thus, you shouldn’t put someone in a position where he or she wants to suggest to use Sie instead of du.

- Note that mostly the polite form is easier to use. You just have to learn a few forms of auxiliary and modal verbs. The main verb is usually the infinitive. With the familiar address you unfortunately have to consider many more irregular verbs.

Subject Pronouns

A

noun is a word that describes a thing or being, e.g. “apple”, “woman”, “man”, etc.

Pronounsare the little words that refer to previously mentioned nouns, e.g. “it”, “she”, “he”, or even “we”, “him”, etc.

The

subject of a sentence is the noun or pronoun that the sentence is about. Usually it is the most active thing or being of the sentence. For example, in the sentence “The woman ate an apple.”, both “woman” and “apple” are nouns, but “woman” is the subject of the sentence because the sentence is about the action performed by the woman. (If you are curious: “apple” is the direct object of the sentence.)

If we replace the nouns of the example by pronouns, the sentence becomes: “She ate it.” In this example, “she” and “it” are pronouns. The subject of this sentence is the pronoun “she” and therefore this kind of pronoun is called a

subject pronoun.

Now that you know about the English subject pronouns, here is a table of them with their German counterparts. Note that

you corresponds to three different words in German, depending on whether you address one or more persons and whether you are using a more formal or more familiar way of addressing them.

Grammar:  Subject Pronouns — Subject Pronouns —  Subjekt-Pronomina Subjekt-Pronomina

|

|

English |

German |

| singular |

1st person |

I |

ich |

| 2nd person |

you |

du, Sie* |

| 3rd person |

he, she, it |

er, sie, es |

| plural |

1st person |

we |

wir |

| 2nd person |

you |

ihr, Sie* |

| 3rd person |

they |

sie |

*

Sie is the formal (polite) version of

du and

ihr.

Names

To say the name of someone or something you can use

to be called —

heißen. You have already seen some forms of the verb

heißen. Here is a more systematic table with all the forms in the present tense. Note that the subject pronouns are capitalized because they start the sentences.

Grammar:  Names — Names —  Namen Namen

|

| English |

German |

| My name is… |

Ich heiße … |

| His/Her/Its name is… |

Er/Sie/Es heißt … |

| Their names are… |

Sie heißen … |

| Our names are… |

Wir heißen … |

| Your name is… |

Du heißt … |

| Your names are… |

Ihr heißt … |

| What is your name? |

Wie heißt du?* |

| What are your names? |

Wie heißt ihr?* |

*Remember, the formal way to ask someone’s name is to ask

Wie heißen Sie?

Note: There

are possessive pronouns (e.g. “my”, “your”, “his”, her”, …) in German, they just don’t apply here. For instance, native speakers usually don’t say

Mein Name ist … (

My name is…).

Important Verbs

Verbs are the words that describe the action of a sentence, e.g.

(to) run,

(to) call,

(to) be, etc.

Conjugation refers to changing the form of a verb depending on the subject of a sentence. For example, the verb

to be –

sein has several different forms:

(I) am…,

(you) are…,

(he) is…, etc. Most English verbs, however, have only two forms in the present tense, e.g.,

(I/you/we/they) run and

(he/she/it) runs. German verbs, on the other hand, have usually several forms in the present tense.

You have already learned the forms of one German verb:

to be called –

heißen.

Verb:  to be called — to be called —  heißen heißen |

|

English |

German |

| singular |

1st person |

I am called |

ich heiße |

| 2nd person |

you are called |

du heißt |

| 3rd person |

he/she/it is called |

er/sie/es heißt |

| plural |

1st person |

we are called |

wir heißen |

| 2nd person |

you are called |

ihr heißt |

| 3rd person |

they are called |

sie heißen* |

*The form of verbs for

you (polite) —

Sie is exactly the same as for the plural, 3rd person pronoun

they —

sie.

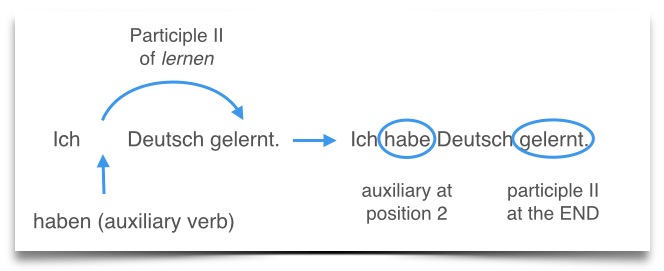

Two extremely common verbs are

to be —

sein and

to have —

haben. They are conjugated like this:

Verb:  to be — to be —  sein sein

|

|

English |

German |

| singular |

1st person |

I am |

ich bin |

| 2nd person |

you are |

du bist |

| 3rd person |

he/she/it is |

er/sie/es ist |

| plural |

1st person |

we are |

wir sind |

| 2nd person |

you are |

ihr seid |

| 3rd person |

they are |

sie sind* |

*Don’t forget that the form for

you (polite) —

Sie is the same as for the plural, 3rd person pronoun

they —

sie.

Verb:  to have — to have —  haben haben

|

|

English |

German |

| singular |

1st person |

I have |

ich habe |

| 2nd person |

you have |

du hast |

| 3rd person |

he/she/it has |

er/sie/es hat |

| plural |

1st person |

we have |

wir haben |

| 2nd person |

you have |

ihr habt |

| 3rd person |

they have |

sie haben* |

*This is also the form for

you (polite) —

Sie.

The Modal Auxiliaries in English:

English features a group of “helping verbs” that function differently from most others: can, may, must, shall, should, and will. They do not describe an action, but express an attitude toward an action usually represented by an infinitive. Their present-tense conjugations resemble the simple past of strong verbs (“the truth will out”), and they do not use “to” when combining with infinitives (“she can go home”). They form past and future tenses in various ways: “I can,” “I could,” “I had been able to,” “I will be able to”). Note also that “to” is omitted when citing the auxiliary verb itself; we do not say “to must.”

The Modal Auxiliaries in German:

The German modal auxiliaries likewise express an attitude toward, or relationship to, an action:

To say on a certain day or the weekend, use am. Add an -s to the day to express “on Mondays, Tuesdays, etc.” All days, months and seasons are masculine so they all use the same form of these words: jeden – every, nächsten – next, letzten – last (as in the last of a series), vorigen – previous. In der Woche is the expression for “during the week” in Northern and Eastern Germany, while unter der Woche is used in Southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

To say on a certain day or the weekend, use am. Add an -s to the day to express “on Mondays, Tuesdays, etc.” All days, months and seasons are masculine so they all use the same form of these words: jeden – every, nächsten – next, letzten – last (as in the last of a series), vorigen – previous. In der Woche is the expression for “during the week” in Northern and Eastern Germany, while unter der Woche is used in Southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

Mein Geburtstag ist im Mai. My birthday is in May.

Mein Geburtstag ist im Mai. My birthday is in May.

In a restaurant, you can get service with the following expressions. Just remember to start with Entschuldigen Sie, bitte! (Excuse me, please!)

In a restaurant, you can get service with the following expressions. Just remember to start with Entschuldigen Sie, bitte! (Excuse me, please!)

When you’re walking around town and need directions on the street, the following questions can help you find your way:

When you’re walking around town and need directions on the street, the following questions can help you find your way: